EuroMillions: Europe’s Weekly Bid to Buy Happiness at a Tabac Near You

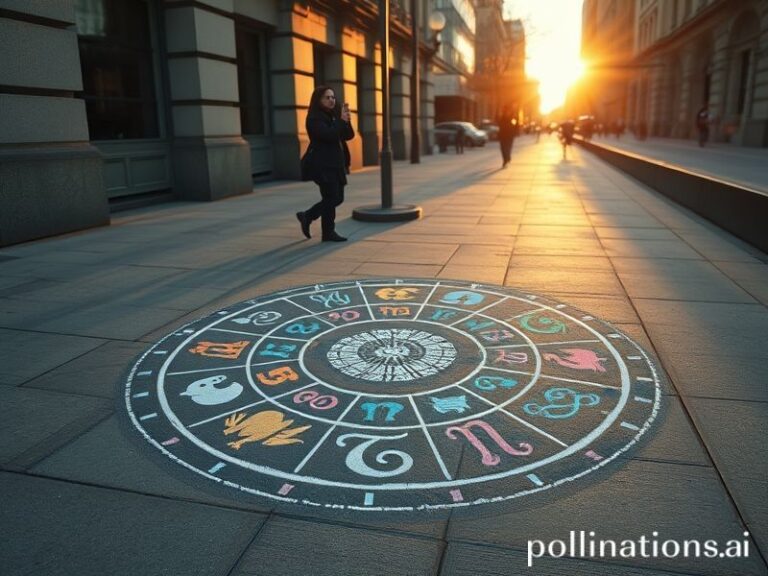

The EuroMillions lottery—Europe’s weekly exercise in collective delusion—draws punters from nine countries who hand over small change in exchange for the statistically negligible possibility that their lives will suddenly resemble a private-jet commercial. Every Tuesday and Friday night the continent pauses, breath baited, to discover which accidental plutocrat will be granted the GDP of a small Baltic state for the price of a cappuccino and a dream.

From Lisbon to Ljubljana, the ritual is the same: queue at the tabac, pick five numbers and two “lucky stars,” then spend the next 72 hours rehearsing conversations with disappointed relatives. The jackpot has ballooned to €240 million on occasion, roughly what the World Food Programme spends in a fortnight feeding 120 million people. One can’t help but admire the elegant symmetry: the same sum that keeps entire nations from starvation can also fund a single individual’s lifetime supply of truffle-flavored crisps.

International finance types like to claim that EuroMillions is a harmless pressure valve for the masses, a sort of fiscal fidget spinner. Yet the cross-border nature of the game makes it a fascinating geopolitical petri dish. Spanish civil servants in Seville buy tickets alongside French nurses and Belgian IT contractors, united by the touching belief that money does, in fact, solve everything. Brussels bureaucrats—those same people who draft 800-page regulations on banana curvature—somehow see no need to legislate against an intra-EU transfer of wealth that makes Robin Hood look like an amateur socialist.

Globally, poorer countries watch this spectacle with the weary fascination usually reserved for slow-motion yacht collisions. In Lagos or Lahore, state lotteries promise motorbikes or a modest house; EuroMillions promises a fleet of motorbikes, a mansion in every EU capital, and a permanent seat at Davos. The result is a thriving gray market of ticket mules: enterprising individuals who hop Ryanair flights to Paris with suitcases of cash from would-be Senegalese millionaires, thereby outsourcing hope to the Schengen zone. European immigration officers, sticklers when it comes to asylum applications, rarely ask too many questions when the traveler is importing foreign aspiration instead of foreign despair.

The draw itself is broadcast in twenty-three languages, a United Nations of disappointment. Watching the numbered balls tumble is oddly soothing—like seeing the very concept of meritocracy reduced to a bingo cage. Winners, when they emerge, face instant canonization by tabloids whose headlines read like parodies of late-stage capitalism: “GRANDMOTHER OF SIX TO BUY THIRD ISLAND.” Within weeks the same papers will run investigative pieces on how the windfall ruined her life, citing a cousin who now refuses to speak to her because the private jet lacked adequate legroom. Schadenfreude, after all, is the continent’s second-favorite currency.

Meanwhile, economists crunch the numbers and discover the obvious: EuroMillions redistributes wealth upward. Roughly half of every euro spent on tickets is returned in prizes; the rest is split between national exchequers and administrative costs that include lavish marketing campaigns featuring grinning retirees on sailboats. In effect, millions of Europeans voluntarily tax themselves to fund government programs they once voted against. It is fiscal policy disguised as Friday night entertainment—bread and circuses with fewer carbs.

And still we play, because the alternative—accepting that the gap between rich and poor is structural rather than numerical—is simply too depressing for a continent that invented existentialism but never quite mastered the art of cheerful nihilism. The true jackpot, perhaps, is the brief, shimmering moment before the numbers are read, when every queue in every corner shop hums with the possibility that physics might take a coffee break and the universe might, just this once, favor the underdog. Then the balls drop, the dream collapses, and everyone shuffles home to check whether their gas bill has gone up again.

Until next Tuesday, anyway.