Sara Cox: The Rochdale Whistle Heard ‘Round the Doomsday Clock

Sara Cox: How a Rugby Referee From Rochdale Accidentally Became a Global Allegory for Everything

By Our Jaded Correspondent, currently self-medicating with airport whisky

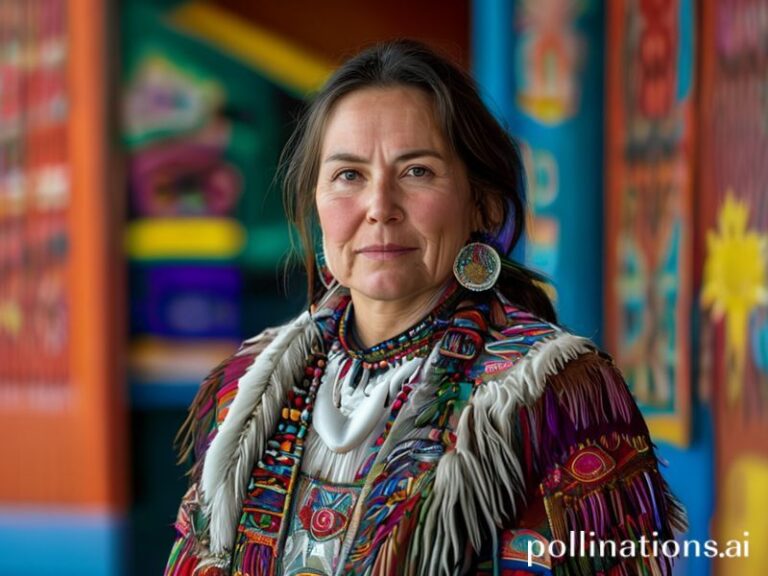

PARIS—The planet is on fire, supply chains are collapsing, and the Doomsday Clock has crept so close to midnight that the minute hand needs a restraining order. Yet in the midst of this slow-motion apocalypse, the world’s media suddenly decided to fixate on Sara Cox—yes, the former dairy-farm kid turned rugby referee from Greater Manchester—because she just became the first woman to take charge of a men’s Rugby World Cup match.

Pause for effect.

In saner times this would be filed under “nice but niche.” Yet in 2023, when geopolitics resembles a drunken pub brawl and the climate resembles a convection oven, Cox’s whistle has improbably become the universal spork with which we attempt to eat the soup of modernity. How did we get here? Simple: the global psyche is so battered it will cling to any half-decent metaphor, preferably one that doesn’t require reading the footnotes on the International Monetary Fund’s latest mea culpa.

Cox’s backstory is almost quaint—daughter of a milkman, grew up refereeing under-9s next to cow patties, once booked a sheep for obstruction (probably). Fast-forward two decades and she’s sprinting down the sideline in Marseille while 60,000 French fans debate her offsides call in five languages and twice as many profanities. The symbolism is so heavy you could pour it over pancakes: a woman from the post-industrial North policing a blood-sport traditionally reserved for the colonial boarding-school set. Somewhere, a think-tank intern is already drafting a white paper titled “Sara Cox and the Soft Power of Ovate Ball Redistribution.”

The Chinese state broadcaster, never one to miss a chance at soft-power judo, ran a seven-minute segment explaining how Cox’s rise proves that meritocracy is superior to “Western chaos,” conveniently skipping the part where Chinese women’s rugby is funded like a hobby horse. Meanwhile, in the United States—a country that treats rugby the way vegans treat steak—ESPN slapped her face between adverts for truck-nut insurance and crypto-vitamin water, branding her “The Beyoncé of Scrums.” Subtlety died somewhere around 2016; we’re just kicking the corpse now.

Down in the Global South, where rugby is either religion or colonial hangover depending on the zip code, reactions split along predictable lines. New Zealand’s prime minister praised Cox for “smashing glass ceilings,” which is rich coming from a nation that still names its team after a 1905 boat. South African commentators celebrated her appointment while quietly praying she wouldn’t notice their forwards’ fondness for neck massages. Argentina simply shrugged; if you’ve survived triple-digit inflation, a female referee feels like the least of your worries.

Back in Europe, the European Commission issued a statement applauding Cox for “promoting gender equality in high-performance sport,” the same week it shelved plans to enforce equal pay for women’s football citing “budgetary headwinds.” Bureaucracies, like teenagers, will always find new ways to disappoint their parents.

And then there’s the money. Multinationals queued up to drape Cox in logos—Visa, Adidas, a cryptocurrency that promises to be carbon-negative by 2047 if you just believe hard enough. Each press release promised “authentic storytelling,” corporate speak for “we’re monetizing your trauma, please smile.” Cox, to her credit, has so far resisted becoming a lifestyle brand; give it six months before she’s selling artisanal scrum-cap scented candles.

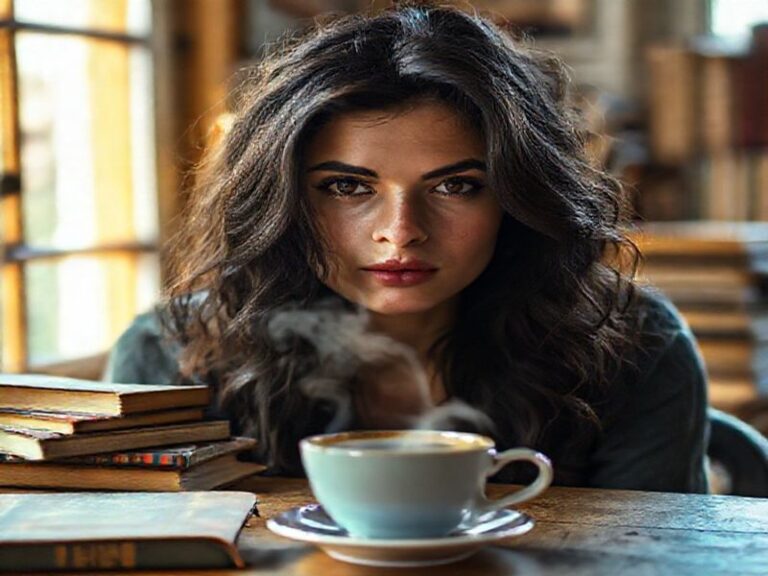

The real punchline, though, is that Cox herself seems vaguely bemused by the circus. Asked by a breathless Australian podcast what it “means” for humanity, she replied she was mostly concerned about the French scrum’s angle and whether she’d left the iron on back in Rochdale. Somewhere in that answer lies the last honest syllable on planet Earth.

So, what does the saga of Sara Cox teach us? That progress is real but fragile. That symbolism is cheaper than structural change. And that, occasionally, a woman from a dairy farm can become the momentary avatar of hope for a species that has otherwise lost the instruction manual. If that strikes you as absurd, congratulations—you’re finally paying attention.