The Global Bengal: Tigers, Tongues, and Touchdowns—How One Word Became the World’s Most Over-Trademarked Predator

CINCINNATI, OHIO—Somewhere between the Mekong Delta and the Ohio River Valley, the word “Bengal” mutates like a passport-forged variant. In Delhi it conjures visions of Royal Bengal tigers padding through Sunderbans mud; in London it evokes the 1970s curry houses of Brick Lane; and here, inside a $650-million riverside coliseum, it refers to a football franchise whose greatest predator is the Internal Revenue Service. Yet the global ripple of this single feline brand is a masterclass in how humanity weaponizes nostalgia, merchandises despair, and—when convenient—outsources identity.

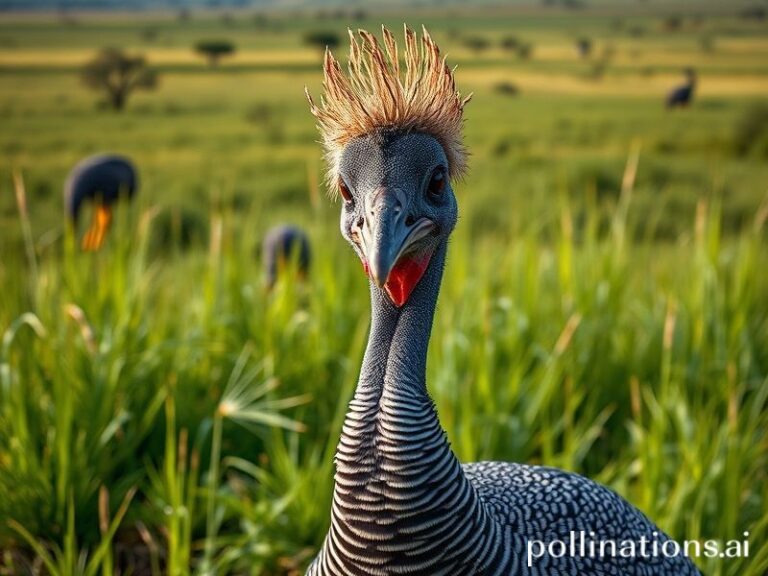

Start with the literal cats. There are now more Bengal tigers in Texas backyards than in the wilds of Asia, a statistic so American it might as well come supersized with a side of fries. The World Wildlife Fund estimates roughly 2,500 mature tigers remain worldwide, a number comfortably dwarfed by the 3.1 million Instagram hashtags #Bengal. Conservationists call this “charismatic-magnet funding”: we will empty our pockets to save an icon, provided we can still plaster that icon on a hoodie. Meanwhile, poaching syndicates from Myanmar to Johannesburg run on Samsung encryption apps and Chinese banking apps that clear faster than a Bengal’s pounce, proving that globalization works best when crime pays in real time.

Pivot to the diaspora. Roughly 260 million people speak Bangla, making Bengal one of the planet’s largest linguistic franchises—think of it as the Coca-Cola of conjugations. The region gave the world micro-finance, Amartya Sen’s welfare economics, and, less auspiciously, the 1943 famine that Churchill once shrugged off as Indians “breeding like rabbits.” Today Bengal’s biggest export isn’t jute or roshogolla; it is skilled labor, harvested by Gulf recruiters who promise “tax-free misery” in 50-degree Celsius Doha camps. The workers wire remittances home, which their families promptly spend on Premier League jerseys—many of them the fetching orange-and-black stripes of a certain Ohio football team whose last championship predates the fax machine.

That team, the Cincinnati Bengals, currently plays inside Paycor Stadium, a corporate naming right that sounds like a fintech app designed to repossess your kidneys. Their mascot, Who Dey, is a linguistic atrocity allegedly stolen from Louisiana Cajuns, who in turn stole it from Caribbean dockworkers, who probably stole it from someone too poor to trademark. Last season the Bengals chased an American Football Conference title while the city outside led the nation in childhood poverty; nothing says civic optimism like cheering a $250-million quarterback from a county where 23 percent of households use payday loans to buy chili-spaghetti.

Still, the NFL markets hope in 4K ultra-HD. International streaming rights now reach 190 countries, meaning a rice farmer in rural Bihar can watch Joe Burrow throw a game-winning touchdown while sitting on a diesel can waiting for the monsoon. The League’s revenue-sharing model is socialism for billionaires: every club splits the pie, ensuring even chronically inept franchises stay profitable—rather like how the UN’s COP climate conferences split carbon credits so everyone can keep emitting, just with guilt-offsets.

And therein lies the broader, gently rotting significance. Whether you’re trafficking in actual tigers, linguistic tigers, or helmeted metaphors, the supply chain is eerily similar: extract, brand, monetize, repeat until extinction—of species, culture, or merely patience. The Bengal is thus a Rorschach test for late-capitalist exhaustion: we see what we need—ferocity, nostalgia, underdog redemption—then swipe right on whatever version ships fastest.

The planet will survive the disappearance of striped fauna, dialects, and even playoff hopes; it has shrugged off worse. What may not survive is our insistence on turning every living metaphor into intellectual property, copyrighted and leveraged until the roar is reduced to a notification ping. In that sense, we are all Bengals now—endangered, franchised, and desperately trying to stay ahead of the poachers, be they in Gucci loafers or government uniforms. Who Dey? We Dey. And Dey is getting very expensive.