Baseball’s World Tour: How America’s Pastime Became the Planet’s Favorite Glorified Tax Write-Off

The Global Pastime Nobody Asked For

By Our Man in the Cheap Seats, Somewhere Over the Pacific

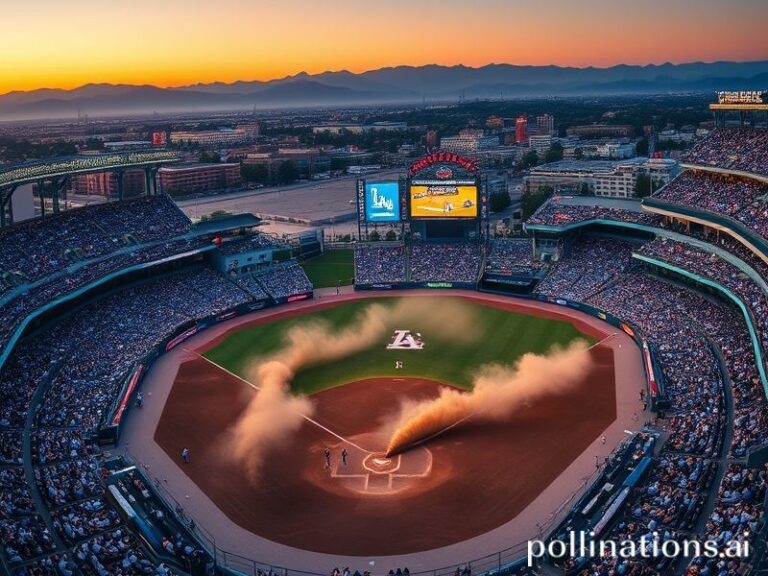

Baseball, that pastoral hallucination of America’s 19th-century leisure class, has spent the last century smuggling itself across borders like a bored customs officer with a side hustle. What began as an excuse for Union soldiers to avoid Civil War skirmishes—“Sorry, Captain, double-header today”—has metastasized into a planetary franchise scheme. From Tokyo to Santo Domingo, Caracas to Seoul, humans now willingly waste four-hour blocks watching grown men adjust batting gloves with the solemnity of surgeons reattaching limbs. Which, in some Caribbean leagues, is not far from the economic reality.

Japan, ever the polite imperialist, domesticated the sport so thoroughly that even the seventh-inning stretch comes with choreographed beer vendors bowing in unison. The Nippon Professional League—where ties are allowed, presumably to preserve everyone’s wa—generates revenues that would make a mid-tier U.S. senator blush. Meanwhile, the Japanese government quietly subsidizes youth academies the way other nations fund missile programs: same nationalist fervor, slightly lower casualty rate. One diamond outside Nagoya features a hotel where parents can livestream their 11-year-olds’ slider spin rates. The breakfast buffet includes free anxiety.

Across the East China Sea, South Korea weaponized baseball into diplomatic theater. Every KBO game is a K-pop concert with pine tar: cheerleaders in neon, thundersticks, and coordinated chants that could restart the armistice if aimed northward. When the Samsung Lions win the Korean Series, Seoul’s stock exchange enjoys a statistically significant uptick—proof that capitalism will eventually price in absolutely everything, including shortstop UZR. The state even granted military-service exemptions to the 2008 Olympic gold medalists, sparing them the usual two-year conscription. Nothing says “thank you for your service” quite like letting you keep your signing bonus.

The Caribbean basin treats MLB less as a sport than as a remittance program with cleats. The Dominican Republic, population eleven million, supplies roughly 11 percent of Major League rosters. In San Pedro de Macorís, every third backyard has a mango tree shading a radar gun. Scouts arrive with stopwatches and promises; mothers pack their sons off with rosaries and protein powder. The local economy hums on signing bonuses large enough to buy generators—useful in a country where the national grid treats electricity as a polite suggestion. When a teenage shortstop inks a $1.5 million deal with the Yankees, the village holds a parade that doubles as disaster preparedness training: same loudspeakers, same evacuation routes.

Cuba, ever the ideological holdout, still insists on amateur “purity,” which translates to state salaries of twenty dollars a month and defections by raft. Havana’s Industriales play in a stadium where the lights flicker like a dying interrogation lamp, yet the infield grass is trimmed with revolutionary precision. When a player escapes to Miami, the regime denounces him as a traitor—then quietly rewrites his Wikipedia page to claim he was actually a volleyball prodigy. The embargo means Cuban prospects must first establish residency in Haiti, because nothing says “path to prosperity” like a layover in Port-au-Prince.

Europe, meanwhile, approaches baseball the way it approaches most American exports: polite curiosity followed by thinly veiled condescension. The Dutch—occupying the imperial afterglow of Caribbean colonies—field a national team that perennially shocks the hemisphere. Italy’s league survives on corporate sponsorship from a parmesan conglomerate; players receive wheels of cheese instead of playoff shares. And in London’s Olympic Stadium, MLB stages annual games where British fans applaud foul balls like Wimbledon aces and queue politely for £14 hot dogs. The British press covers it as anthropological fieldwork: “Colonists Discover Rounders, Add Gloves.”

The broader significance? Baseball has become a global laundering service for hope. It converts raw athletic desperation—whether Dominican sugarcane dreams or Korean conscription dread—into fungible assets traded on sportsbook apps. Every time a teenage catcher signs for seven figures, a hedge fund somewhere hedges yen volatility against his exit velocity. The game itself remains a stately pantomime of failure: even the best hitters are wrong 70 percent of the time, a batting average the IMF would call catastrophic.

But perhaps that’s the point. In a world where geopolitics rewards nuclear tantrums and algorithmic spite, baseball offers the consoling illusion that three strikes and you’re out is a rule nature might still respect. Spoiler: it doesn’t. Ask Venezuela, where the government recently nationalized the winter league and now blames the mound for inflation. The bases are loaded, the lights are flickering, and the closer just tore his UCL. Play ball—until the creditors foreclose the stadium.