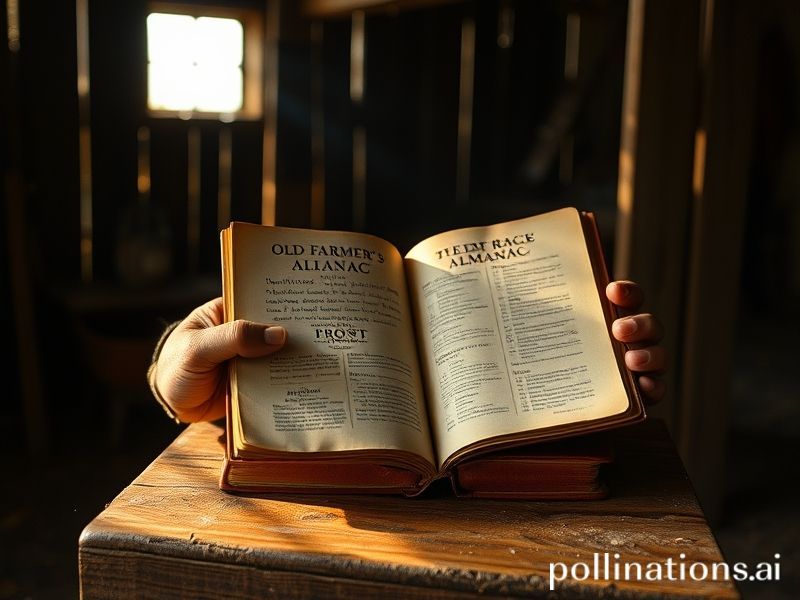

Global Weather Prophet: How America’s 232-Year-Old Farmer’s Almanac Became Humanity’s Favorite Climate Delusion

**The Global Oracle: How a 232-Year-Old American Farmer’s Diary Became the World’s Most Unexpected Climate Prophet**

In a world where billion-dollar satellites can’t predict tomorrow’s weather but your grandfather’s knee can, the Old Farmer’s Almanac stands as humanity’s most charming anachronism—a publication that somehow remains relevant despite using planetary positions and “secret formulas” that would make a Renaissance alchemist blush.

While Silicon Valley burns through venture capital trying to disrupt the weather, this yellowing booklet—first published when America was still experimenting with democracy and smallpox—continues to sell three million copies annually. That’s roughly one for every person who actually understands how cryptocurrency works, though significantly more useful during a power outage.

The Almanac’s international significance lies not in its accuracy—though boasting 80% correctness rates that would get you fired from any respectable meteorological service—but in its stubborn refusal to acknowledge that the Enlightenment happened. While European weather services employ supercomputers that could simulate the Big Bang, the Almanac’s editors remain faithful to a formula developed in 1792 by Robert B. Thomas, a man who presumably believed lightning was God’s way of expressing displeasure with the French.

Yet herein lies its perverse genius: in an era of climate anxiety where every weather app sends push notifications about humanity’s impending doom, the Almanac offers something Silicon Valley can’t algorithmically generate—certainty, however fabricated. It’s the meteorological equivalent of your grandmother’s advice: probably wrong, but delivered with such conviction that you find yourself planning your vacation around it anyway.

The publication’s global reach extends far beyond America’s borders, with Canadian editions that politely apologize for predicting snow and Australian versions that somehow explain weather patterns upside-down. International farmers from Patagonia to Punjab have been known to consult it, though whether this represents agricultural optimization or agricultural desperation remains an open question worthy of academic study.

What makes the Almanac particularly fascinating in our current moment is its unwitting commentary on climate change. When its predictions prove spectacularly wrong—say, predicting a mild winter while your pipes freeze solid—it’s not the formula’s fault, oh no. It’s clearly evidence that the natural order has been disrupted by human hubris. Nothing validates your apocalyptic worldview quite like a 19th-century weather oracle failing to predict a Category 5 hurricane.

The publication’s endurance reveals something profound about human nature: our species would rather trust mystical calculations involving sunspots and “opposing planet positions” than acknowledge that we’ve thoroughly broken the planet’s thermostat. It’s comfort food for the climate-anxious soul—predictions seasoned with just enough scientific-sounding terminology to feel legitimate while avoiding the unpleasant truth that weather patterns have become about as predictable as a cryptocurrency market during a full moon.

Perhaps the Almanac’s greatest service to humanity is providing conversational fodder for people who want to discuss the weather without discussing the weather, if you catch my meaning. It’s the perfect distraction from those awkward conversations about why your beach vacation photos now feature underwater photography or why ski resorts are investing in water parks.

As we stumble deeper into the Anthropocene, clutching our smartphones like digital rosary beads, the Old Farmer’s Almanac serves as a poignant reminder that sometimes the most sophisticated response to chaos is maintaining elaborate fantasies about controlling it. In a world where actual climate scientists lose sleep over feedback loops and tipping points, there’s something almost heroic about a publication that faces uncertainty with nothing more than folklore, mathematics developed before electricity, and the audacity to charge $7.99 for the privilege of being wrong in advance.