Kissing Bug Disease Goes Global: How a Parasitic Casanova Conquered Five Continents While We Weren’t Looking

The Diplomat of Diseases: How a Tiny Kissing Bug Became a Global Gate-Crasher

By L. Sinclair, Foreign Correspondent-at-Large

If romance had a vector, you’d expect roses, violins, or at least a half-decent dating app. Instead, the Western Hemisphere’s most ardent suitor is a thumb-sized assassin in a striped waistcoat: Triatoma infestans, better known as the “kissing bug.” It sidles up to sleeping lips, slips a syphoning straw through tender skin, and—because manners matter—defecates bedside. The itch that follows smears infected feces into the wound. Cue Chagas disease, a parasitic love letter that may take twenty years to break your heart … literally.

For decades, Latin America filed this ailment under “local color,” somewhere between tequila worms and telenovela plot twists. Chagas killed quietly—about 12,000 people a year—while cardiologists blamed “idiopathic” heart failure and grandmothers blamed brujería. Then globalization did what globalization does: it put the bug on Expedia. Blood banks in Madrid, Paris, and Washington began screening for Trypanosoma cruzi. Obstetricians from Geneva to Geneva-on-the-Lake discovered congenital cases. In 2006, a Bolivian migrant in Sydney became Australia’s first domestic transmission; the culprit was a kissing bug that had bunked in her suitcase like a very dedicated stowaway. The insect hadn’t evolved wings, but it had acquired baggage allowances.

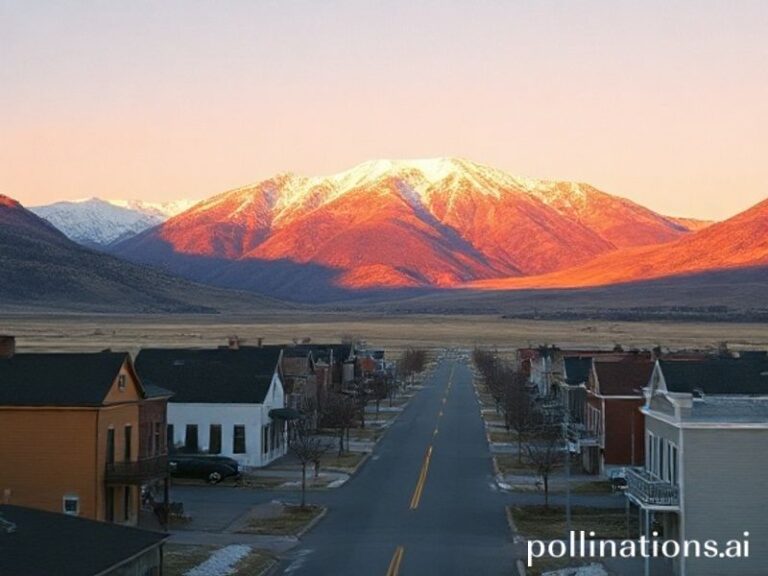

The World Health Organization now estimates 7 million infected worldwide, with 75 million at risk. That’s roughly the population of Turkey, or, for readers of a more cynical persuasion, the number of Netflix subscribers who swear they’ll cancel after the next price hike. The disease’s new passport stamps reveal an uncomfortable truth: Chagas isn’t just a poverty story, it’s a mobility story. Climate change nudges the bugs northward—Texas and Tennessee have resident colonies—while rural-to-urban migration stuffs Latin American laborers into substandard housing in Madrid and Barcelona. Europe’s austerity-era bricklayers sleep in shacks without window screens; the bugs obligingly commute. In a delightful irony, the same remittances that build concrete mansions back home finance leaky hostels abroad. The parasite, ever the economist, simply follows the money.

Pharmaceutical interest remains tepid. The two available drugs, benznidazole and nifurtimox, were developed when Nixon was still taping himself. They work best on children, taste like burnt pennies, and can trigger neuropathy that makes your toes throw their own independence parade. Big Pharma prefers oncology or hair-loss, where margins are fatter and patients don’t vanish for decades. The Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative cobbles together grants like a college student trying to pay rent, while patent-holders occasionally dangle “access programs” that resemble charitable breadcrumbs sprinkled over a banquet they’re too full to finish.

Rich countries have responded with the enthusiasm of a vegan at a chorizo festival. The U.S. spends more annually on erectile dysfunction ads than on Chagas surveillance. The EU’s new Global Health Strategy mentions the disease once—between “antimicrobial resistance” and “something about mosquitoes”—which is diplomatic speak for “thoughts and prayers.” Meanwhile, blood banks quietly foot the bill, because nothing says soft power like screening for parasites at 3 a.m. between episodes of reality TV.

Yet the broader significance transcends entomology. Chagas is a preview of climate-assisted diseases that respect no border guard. Dengue in Paris, Zika in Texas, malaria in Greece—each is a postcard from a warming world that still believes passports are waterproof. The kissing bug teaches a lesson our leaders keep flunking: pathogens are better diplomats than we are. They negotiate trade deals at body temperature and ratify treaties during REM sleep.

The cure, such as it exists, is tediously unsexy: improved housing, window screens, vector control, maternal screening—bureaucratic foreplay in an era addicted to miracle vaccines and TED-talk salvation. Until then, the bugs will keep French-kissing their way across continents, reminding us that the most intimate acts are often the least consensual.

Sweet dreams, planet Earth. Don’t forget to check under the pillow.