Stuart Craig’s Hogwarts: How a British Production Designer Conquered the World One Gothic Arch at a Time

Hogwarts, NATO, and the Gentle Art of Gothic Soft Power

A dispatch on Stuart Craig, Harry Potter, and the architectural export of British melancholy

By the time Stuart Craig finished sketching the first crooked gable of Hogwarts, Boris Yeltsin was still busy auctioning off the Soviet Union and the world’s newest worry was whether dial-up modems could give you cancer. Thirty years later the castle that Craig conjured—part Durham Cathedral, part fever dream of an Oxbridge dean who’s read too much Mervyn Peake—has become the most globally recognised piece of British real estate since the East India Company’s ledgers. UNESCO doesn’t list Hogwarts (yet), but it might as well: the films have grossed $7.7bn, spawned theme parks on four continents, and provided the backdrop for approximately 97 % of the world’s engagement photos shot between 2011 and 2019.

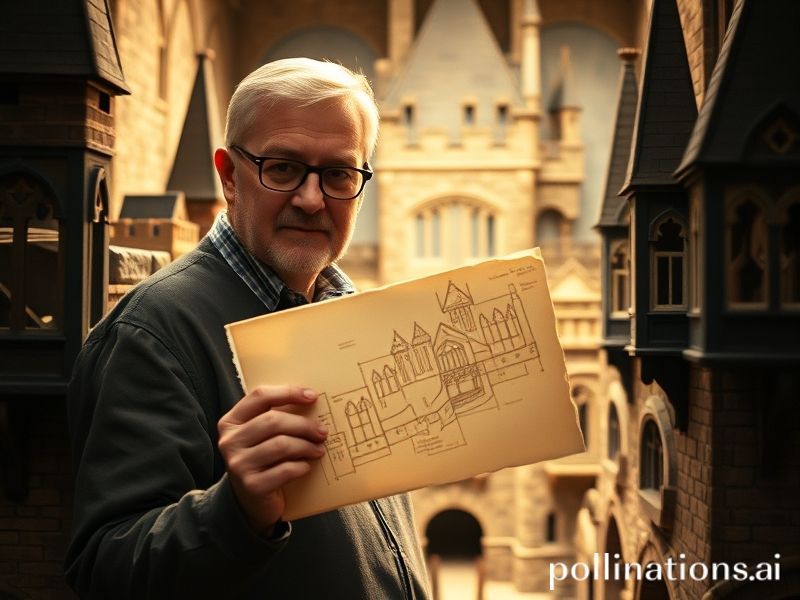

Craig, production designer on every Potter film from Philosopher’s Stone to Deathly Hallows Part 2, is the quiet bureaucrat of this soft-power coup. While J.K. Rowling collected royalties and death threats in equal measure, Craig was busy deciding whether the Great Hall should have hammer-beam trusses or Perpendicular Gothic fan vaulting—choices that now dictate what Chinese teenagers picture when they imagine “old Europe”. His sets have become the wallpaper for a planet that can’t decide if it’s more afraid of climate collapse or its own TikTok feed.

You’ll find Craig’s fingerprints in the oddest places. In Lagos, bootleg DVD stalls hawk grainy copies of Prisoner of Azkaban next to Nollywood romances; the kids queueing up don’t know who Stuart Craig is, but they know a gargoyle when they see one. In Dubai, the Warner Bros. Studio Tour sells VIP packages to Emirati influencers who want to sip butterbeer under vaulted stone that is, in fact, fibreglass sprayed with a proprietary “ancient soot” finish. Meanwhile, somewhere in the Carpathians, a property developer is currently pitching “Transylvanian Hogwarts” apartments to Russian oligarchs—because nothing says safe haven asset like a turret.

The joke, of course, is that Craig’s Britain never really existed. The films were shot in a country that had already sold off its railways, privatised its water, and was busy turning every provincial high street into a Costa Coffee museum. Hogwarts is the Britain the rest of the world still wants: rain-soaked, sarcastic, reassuringly hierarchical. It’s boarding-school cosplay for an age when actual boarding schools are being converted into luxury flats for Saudi art students.

And yet the brand travels. When the Ukrainian city of Lviv needed to boost winter tourism after 2014, it built a pop-up “Hogwarts courtyard” in the snow; the BBC ran a chipper segment titled “Lviv Expecto Patronum!” as if war-crime allegations were merely a subplot. In post-Brexit London, the government’s “Great Britain” trade campaign features Craig’s castle silhouetted against a Union Jack, because nothing says “open for business” like a fictional school that teaches children how to turn teacups into hedgehogs.

Cynics will point out that Hogwarts is also a perfect emblem for modern Britain: perpetually broke, structurally unsound, and run by a headmaster who keeps the darkest secrets in his office drawer. The difference is that in the films the kids eventually graduate. In the real UK they inherit £50k of student debt and a housing market guarded by dementors in Savile Row suits.

Still, give Craig credit: he built a monument that survived longer than most nation-states. The Berlin Wall lasted 28 years; the Soviet Union, 69. Hogwarts—fake stones, real myth—has already clocked 23 and shows no sign of crumbling. Somewhere in a Los Angeles archive, the original blueprints are presumably filed under “Soft Power, Grade A, Do Not Fold”. Across the world, children who will never visit Durham Cathedral still dream in Stuart Craig’s stone corridors, practising their Latin in accents borrowed from BBC drama.

Empires fall, currencies collapse, but gothic arches—especially ones with CGI dragons circling overhead—turn out to be surprisingly inflation-proof. That’s the real magic spell: convincing seven billion people that a damp castle in the north of nowhere is the centre of the universe. All it took was one quiet man with a pencil, a nation in decline, and a planet desperate for somewhere enchanted to hide from itself.