Tea, Empathy & Invoices: How UK Charities Became the World’s Offshore Morality Refinery

If you squint at a map of the United Kingdom long enough, the country starts to resemble a Victorian teapot: ornate, slightly cracked, and forever pouring something out for someone else. That “something” today is roughly £10 billion a year, funnelled through 168,000 registered charities—enough NGOs per square mile to make Davos feel under-populated. From an international perch, Britain’s charitable-industrial complex looks less like altruism and more like an offshore morality refinery: crude guilt goes in, polished virtue comes out, and the fumes are vented over everyone else.

Take the global brand Oxfam, which began life in 1942 as the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief and now has the budget of a midsize sovereign wealth fund. When its staffers were caught in 2018 trading aid for sexual favours in post-quake Haiti, the scandal ricocheted from Port-au-Prince to Whitehall to the Australian outback, where donors suddenly discovered their monthly direct debit had been underwriting a Caligula-themed gap year. Cue parliamentary hand-wringing, a Charity Commission inquiry, and—this being Britain—tea. The affair confirmed an iron law of humanitarianism: the farther the crisis, the more creative the expense receipts.

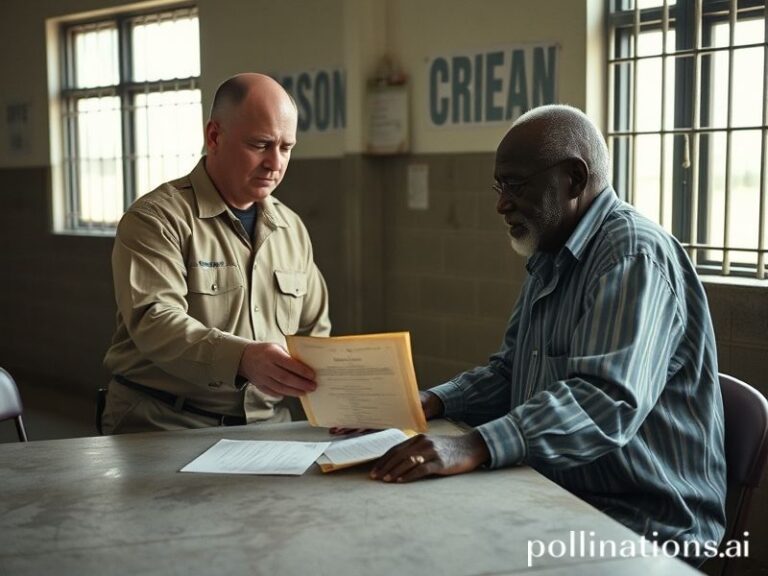

Yet the reputational mushroom cloud had a silver lining for other UK charities. Donors, horrified at the thought of their guilt money funding beachside frolics, simply rerouted it to smaller, “cleaner” outfits with reassuringly wooden logos. The sector, like a well-drilled rugby scrum, absorbed the impact and shuffled on. Meanwhile, the Haitian government—whose own budget is roughly what the British spend annually on dog Christmas presents—was left explaining to its citizens why foreign do-gooders still enjoy diplomatic immunity for sins that would land locals in a Port-au-Prince jail with a complimentary rodent roommate.

Zoom out and you see the same pattern everywhere British charities operate. In Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees huddle under tarps stamped with the Union Jack and the discreet logo of a Surrey-based housing charity. In eastern Congo, where cobalt for your smartphone is mined by children with the life expectancy of a fruit fly, UK NGOs run trauma workshops whose flip-chart budget exceeds the miners’ annual wages. The moral arithmetic is brutally simple: a nation that once ran the planet now soothes its post-imperial hangover by air-dropping empathy onto the grandchildren of the people it once subjugated. Think of it as emotional reparations, payable in tote bags.

Of course, the British are hardly alone in weaponising generosity. Scandinavian governments dump surplus SAS crisps on famine zones; American evangelicals baptise drought victims before handing out the bottled water. But the UK’s particular genius is to monetise guilt at scale. Charitable giving is now baked into the tax code—Gift Aid allows the Treasury to top up donations by 25%, essentially laundering public money through private consciences. The result is a virtuous circle: the more you give, the less you owe Her Majesty, and the more smug you feel about both.

Brexit, that slow-motion national seppuku, has only turbocharged the trend. Deprived of easy access to continental holiday homes, the English middle classes have redirected their disposable income towards “gap-year engineers” building eco-toilets in Laos. The government, eager to prove “Global Britain” still has friends, now channels foreign aid through NGOs faster than you can say “Singapore-on-Thames.” The irony is exquisite: having voted to take back control, Britain now outsources its soft power to twentysomething volunteers with GoPros and an Instagram handle like @Posh4Progress.

Which brings us to the broader significance. In an era when nation-states increasingly resemble indebted shopping malls, charities have become the pop-up stores of geopolitics—nimble, photogenic, and accountable only to trustees who meet in agreeable Cotswolds pubs. They allow Western publics to feel engaged without the inconvenience of actual politics, and they let recipient governments blame foreign meddlers when projects inevitably collapse. Everyone wins, except perhaps the intended beneficiaries, who must add “consulted to death” to their list of daily hazards.

So the next time you see a British charity appeal featuring a photogenic child holding a goat, remember: somewhere in Whitehall, a spreadsheet is breathing a sigh of relief. The goat may or may not survive, but the moral balance sheet will be spotless. And that, dear reader, is the true special relationship: between a fading empire’s guilty conscience and the rest of the world’s infinite capacity to invoice it.