Bibury: The Tiny English Village Being Loved to Death by the Entire Planet

Bibury, Gloucestershire – population 627, average blood pressure 180/110 once the tour buses arrive – has become the unlikely barometer for a planet that can’t decide whether it wants to be Instagrammed or left the hell alone. On paper it’s merely a Cotswold hamlet: honey-coloured stone, trout stream, a row of 14th-century weavers’ cottages so quaint they make Disney’s imagineers look like brutalists. In practice, Bibury is the place where global contradictions come to practice their smile for the camera while quietly plotting murder-suicide.

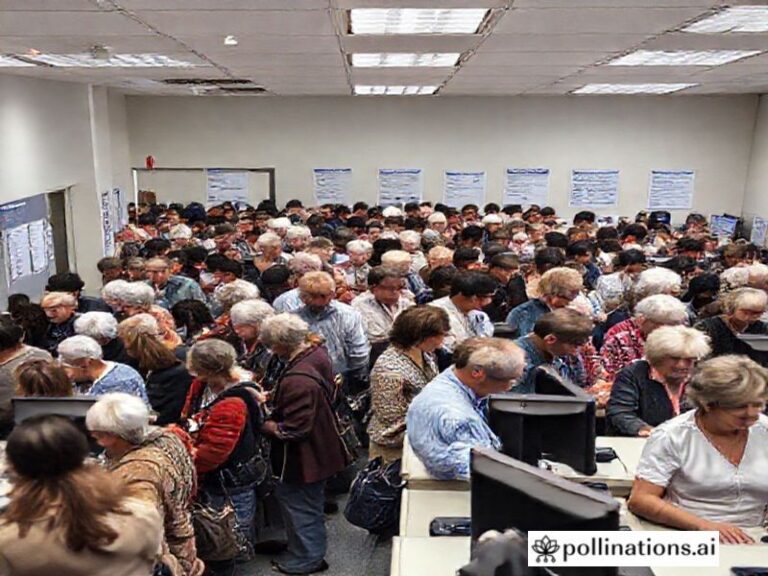

First the numbers, because we all worship at the spreadsheet now. Roughly 750,000 visitors descend annually—more than a thousandfold multiplier on the local headcount. That’s one foreign footfall for every blade of grass, give or take a few blades the tourists have nicked for scrapbooking purposes. Coach parties from Shenzhen, Osaka, and Düsseldorf queue politely on Arlington Row, the cottages William Morris once called “the most beautiful in England,” which today double as the most extensively hashtagged #wattleanddaub on Earth. Each selfie, naturally, is captioned with some variation of “hidden gem,” a phrase that has come to mean “I was here thirty seconds before you.”

The environmental calculus is deliciously grim. A return flight from Shanghai to Heathrow spits out roughly 1.9 tonnes of CO₂ per economy seat—enough to melt a small glacier or, more practically, to power Bibury’s 400-year-old stone for about three centuries. Multiply by planeload after planeload of visitors who come to “get away from it all,” and the moral arithmetic starts to resemble a Soviet tractor statistic: impressive on the ledger, catastrophic underneath. Still, the trout don’t vote, and the National Trust tea shop now accepts Alipay, so net win, right?

Culturally, Bibury is the petri dish where heritage and hypermodernity cough on each other. The local council recently installed discreet QR codes on the stone walls so visitors can scan for 360-degree VR versions of the same view they’re physically blocking. Meanwhile, villagers—those who haven’t sold up and retired to somewhere quieter, like the Gaza Strip—report a roaring trade in “authentic Cotswold fudge” made in an industrial unit outside Birmingham and shrink-wrapped in plastic that will outlast the cottages themselves. The fudge tastes faintly of existential dread, but it photographs well.

The broader significance? Bibury is simply the most photogenic canary in our collective coal mine. From the lavender fields of Valensole to the blue domes of Santorini, the planet is being loved to death by a species that can’t experience beauty unless it’s been throttled, monetised, and uploaded at 5G speed. UNESCO calls it “geotourism”; the rest of us call it the slow conversion of everywhere into a backdrop for someone else’s personal brand. Even North Korea has cottoned on: state media recently boasted of a forthcoming “Bibury-style village” near Pyongyang, presumably minus the inconvenient democracy and plus compulsory Kim-themed souvenir spoons.

And yet, and yet. On certain Tuesdays in January, when the skies dump sleet and the tour coaches hibernate, you can still hear the trout stream argue with itself and catch the scent of woodsmoke that hasn’t been piped in by an aromatherapy diffuser. Locals—those who remain—gather in the Catherine Wheel pub to grumble about tourists in the time-honoured manner of people whose mortgage is paid by them. For a few hours Bibury reverts to being a village rather than a lifestyle accessory. Then the sun rises on Wednesday, TripAdvisor pings, and the whole circus rolls back into town, carbon footprint first.

So file Bibury under “quaint little warning sign.” It’s the postcard we send ourselves from a future where every square inch of the planet is either a souvenir shop or a no-go exclusion zone. Until then, smile for the drone, mind the queue, and remember: the most authentic experience left is the creeping realisation that authenticity itself has been discontinued due to popular demand.