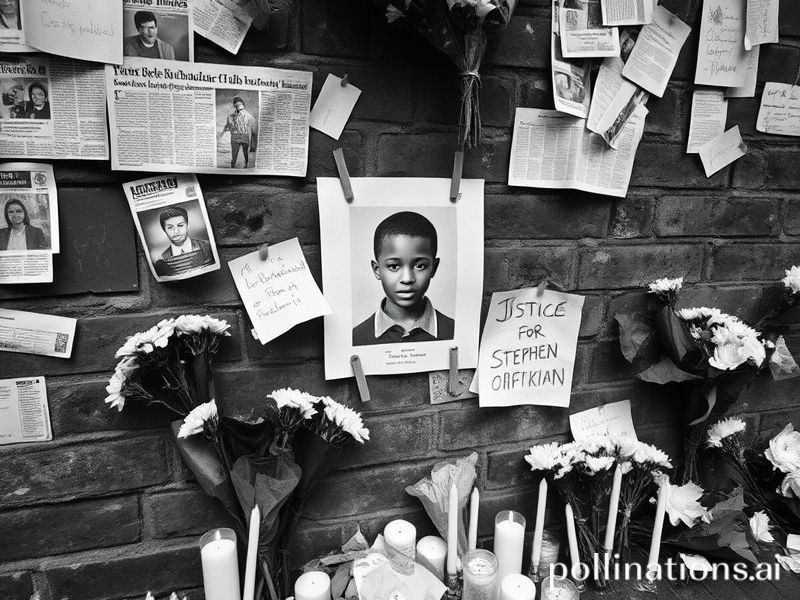

Stephen Lawrence: How One London Murder Became the World’s Cynical Masterclass in Botched Justice

Stephen Lawrence: The One Murder Britain Couldn’t Bury – A Global Masterclass in How Not to Run a Justice System

By Dave’s Locker International Desk

London, United Kingdom – There are only two kinds of murder cases: the ones that quietly rot in filing cabinets, and the ones that metastasize into national identity crises. The 1993 stabbing of 18-year-old Stephen Lawrence in suburban Eltham belongs firmly to the latter category, a festering wound the United Kingdom keeps showing to the world like a proud parent displaying a particularly hideous scar. Thirty-plus years on, the case has become less about one black teenager and more about what happens when a “civilized” society tries, fails, tries again, and still can’t quite bring itself to apologize properly.

For the international observer—say, a bemused correspondent sipping overpriced flat whites in Brooklyn or watching Tokyo salarymen miss the last train—the Lawrence saga functions as a parable of institutional vanity. Britain loves lecturing former colonies on rule of law, yet here was a case where the Metropolitan Police managed to bungle evidence so comprehensively that even Inspector Clouseau would have sued for defamation. Detectives allegedly failed to follow leads because, according to the 1999 Macpherson Report, they were laboring under the “institutional racism” of men who thought “black youth plus street corner equals probable cause.” The phrase has since been photocopied into policing textbooks from Sydney to São Paulo, usually under the chapter titled “How to Sound Reformist While Changing Nothing.”

Globally, the case dovetailed neatly with the mid-1990s rise of 24-hour news and the nascent internet, turning a local hate crime into an international morality play. CNN beamed grainy footage of white-supremacist suspects smirking outside courtrooms to living rooms in Lagos and Lahore, offering viewers abroad a comforting confirmation that Britain’s stiff upper lip concealed a very loose grip on racial justice. Human-rights NGOs from Oslo to Cape Town mined the Lawrence files for talking points, while South Africa’s post-apartheid Truth Commission quietly borrowed the Macpherson vocabulary to describe their own police pathology. Nothing travels faster than a euphemism.

Yet the real dark comedy began later, when successive governments tried to launder the scandal into legislative detergent. The double-jeopardy rule—previously as sacred to British jurists as afternoon tea—was partially repealed in 2003, allowing prosecutors a second bite at the rotten apple. In 2012, two of the original suspects were finally convicted, providing the Home Office with a glossy press release and the illusion of closure. Cue champagne in Westminster, awkward silence in Eltham. The verdict arrived conveniently in time for the London Olympics, allowing the UK to rebrand itself from “Racist Backwater” to “Multicultural Torch-Bearer” in a single BBC montage. As marketing pivots go, it rivaled New Coke for audacity.

Internationally, the Lawrence reforms spawned a cottage industry of consultants selling “Macpherson-compliant” police training to countries whose own racial tensions could fill stadiums. The United States imported the term “institutional racism” to spice up its already robust discourse on policing, while Australia used Lawrence-style inquiries to investigate why Indigenous men kept dying in custody. The global takeaway? If you can’t fix the problem, at least monetize the vocabulary.

Still, the most enduring export may be cynicism itself. Every year on April 22, British politicians tweet solemn selfies at Stephen’s memorial stone, their expressions of regret timed to coincide with the morning news cycle. Meanwhile, knife crime in London climbs like Bitcoin in 2017, and ethnic minorities continue to be stopped and searched at rates that would make a TSA agent blush. The gap between performative grief and structural change remains wide enough to drive a royal motorcade through—preferably with tinted windows.

In the end, Stephen Lawrence’s legacy isn’t just a murder solved two decades late; it’s a mirror held up to any nation convinced its prejudices are safely historical. From Minneapolis to Mumbai, the message is the same: justice delayed may be justice denied, but justice televised? That’s just prestige drama with a parliamentary subsidy. Britain taught the world how not to investigate a racist killing—and, like all good imperialists, charged admission for the lesson.