From Popcorn to PowerPoints: How Terrell Owens Became the World’s Favorite American Parable

PARIS—Somewhere between the Champs-Élysées and a dimly lit sports bar in Lagos, the name Terrell Owens still triggers the same half-smirk: the universal facial expression that says, “Yes, I remember the popcorn, the push-ups, and the existential dread of being very good at catching leather in a collapsing empire.”

From the vantage point of a planet now more interested in geopolitical food fights than gridiron melodrama, Owens looks less like a retired wide receiver and more like a living cautionary emoji—an avatar of what happens when raw athletic genius collides with the global attention economy, then ricochets off every available ego.

Europeans, who long ago outsourced their tribal bloodlust to Champions League riots, watch Owens highlights with anthropological detachment. To them he is a study in American excess: a man who once celebrated a touchdown by pulling a Sharpie from his sock and autographing the ball, as if the stadium were an eBay pop-up. The French call it “performative narcissism”; the Germans call it “very on-brand for late-stage capitalism”; the Brits just mutter “cheeky wanker” and order another pint.

Asia’s reaction is more pragmatic. In Seoul’s Gangnam district, startup founders cite Owens’ “personal brand velocity” in pitch decks, right next to the slide about leveraging K-pop influencers for synergy. In Mumbai, call-center managers play Owens sound bites during morale seminars: “Get your popcorn ready!” is apparently motivational when you’re explaining a billing error to someone in Iowa at 3 a.m. local time.

Latin America, bless its melodramatic soul, still loves the myth more than the man. In Buenos Aires they compare him to Maradona—another divinity who moonlighted as a human telenovela—while in Rio, samba schools have considered a Terrell-themed float: golden helmet, Sharpie raised like Excalibur, flanked by dancers dressed as rejected NFL owners.

The Middle East finds Owens useful as a parable. In Dubai, management consultants use his career arc—explosive early success, mid-career self-sabotage, late-stage redemption tours in the Indoor Football League—as a PowerPoint fable about avoiding “talent hubris.” The irony, of course, is that the consultants themselves are billing $2,000 an hour to tell this story in a desert built by indentured labor.

Africa watches with a knowing shrug. Lagos radio hosts joke that Owens would have made a great Nigerian email scam—promise the world, deliver sporadically, then blame the quarterback. Meanwhile, in Senegal, kids playing beach soccer wear knockoff Owens jerseys, the name peeling off in the salt air like an allegory for post-colonial hope.

And then there’s the United States, where Owens is currently suing the Hall of Fame for the right to skip his own induction ceremony—an act so perfectly American it could be bottled and sold as artisanal irony. The lawsuit is quintessential late-empire behavior: achieve immortality, then litigate over the seating chart.

Globally, the takeaway is less about football than about the transaction we all make with fame. Owens maximized his fifteen minutes into a lifetime subscription—he monetized grievance, turned narcissism into NFT before NFTs existed—and now drifts through reality-TV purgatory like a ghost with excellent vertical leap.

In the end, Terrell Owens is the world’s mirror: a reminder that talent can scale borders, but ego remains stubbornly local. Whether you’re sipping espresso in Rome or yak-butter tea in Lhasa, the plot stays the same: rise, shine, implode, reboot, repeat. The popcorn is always ready; the planet just keeps popping.

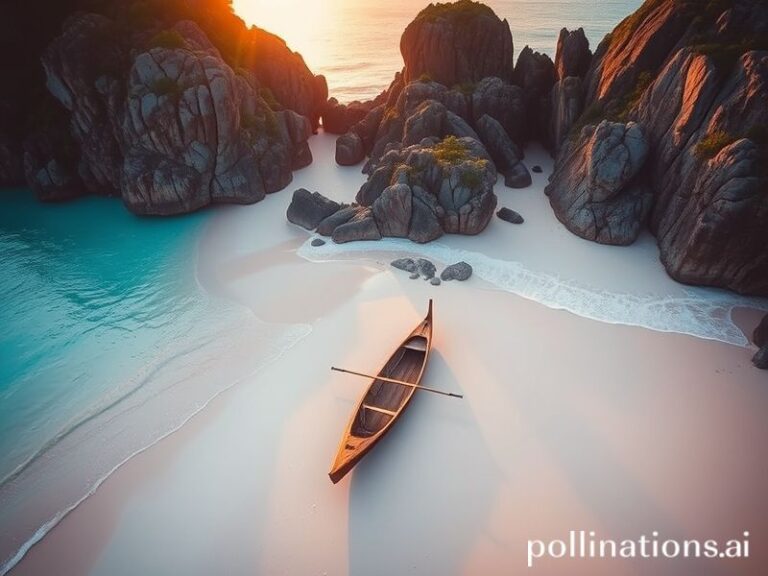

And somewhere, on a yacht off Monaco, Owens is probably filming an Instagram story, Sharpie still holstered like a sidearm, caption reading “Still open, just in case the universe wants to run a fly route.” Spoiler: the universe already scored, and Terrell’s still waiting for the replay review.