Empire Strikes Out: How the New York Mets Became a Global Metaphor for American Overreach

The Mets and the End of Empires

A dispatch from the front row of American decline, as told through nine innings of exquisite mediocrity

By the time the New York Mets staggered into June, having already misplaced two starting rotations, a bullpen, and whatever remained of the Steinbrenner-era illusion that money guarantees anything more than a slightly better class of disappointment, the rest of the planet had learned to watch them the way archaeologists once watched Rome: with notebooks, tweezers, and the quiet certainty that every spectacular collapse contains clues about why civilizations eventually trade their legions for TikTok dances.

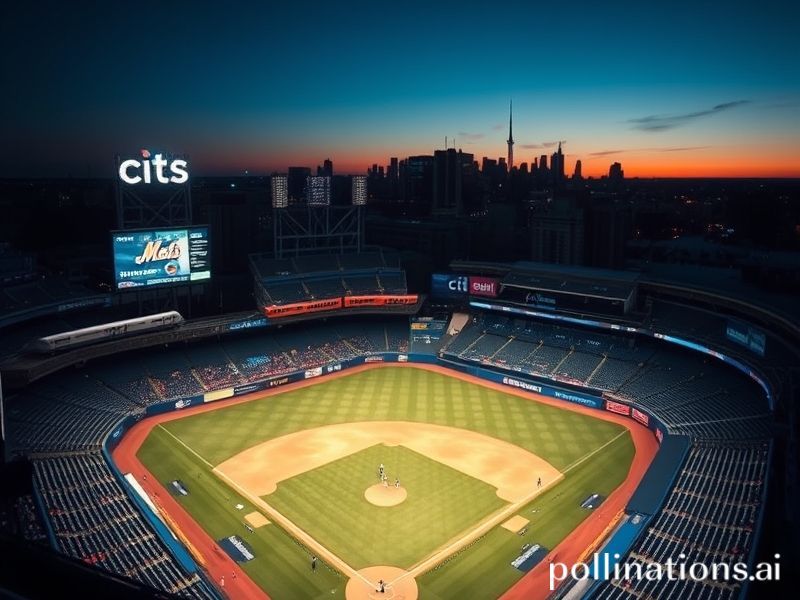

From the vantage of a press box high above Citi Field—an ironically pastoral name for a ballpark wedged between a junkyard and the eternal traffic clot of the Grand Central Parkway—the Mets look less like a baseball team than a geopolitical forecast. Their owner, Steve Cohen, is a hedge-fund potentate whose net worth fluctuates with the same caprice as the Turkish lira. Their payroll is north of $350 million, a figure that exceeds the GDP of Micronesia and, until recently, inspired the same sort of nervous awe that the Pentagon budget once did in lesser capitals. Yet here they are, 10 games under .500, proving that late-capitalist excess can still be humbled by a pulled oblique and a 38-year-old designated hitter who suddenly can’t see a curveball.

The international implications are not trivial. In Seoul, the KBO’s LG Twins have started live-streaming Mets games as a morale booster: “Watch the rich fail in real time,” the promos promise. In London, where the Mets will play next season’s “MLB World Tour” (a branding exercise roughly as global as a Marriott breakfast buffet), pub quiz masters now use the team’s run differential as shorthand for American overreach. Even the Swiss—neutral since 1815—have taken to muttering “Mets-ing it up” whenever a Credit Suisse merger wobbles. Linguists note the verb is spreading: in Nairobi traffic jams, matatu drivers blame “metsing” the route; in Paris, pastry chefs claim their soufflé has been “completely Metsed.”

Back in Queens, the faithful still file in, armed with enough existential resignation to qualify for EU citizenship. They wear jerseys commemorating players who were traded, injured, or forgotten faster than a Brexit promise. Between innings, the scoreboard encourages them to download an app that will let them order a $19 michelada directly to their seat, because nothing soothes the sting of existential dread like cold lime beer delivered by a teenager earning less per hour than the foam costs. The whole ritual feels like an open-air seminar on late-stage empire: bread, circuses, and a 5.87 team ERA.

Naturally, there are geopolitical metaphors everywhere. The Mets’ defense resembles the European Union—expensive, bureaucratic, and prone to leaks. Their offense channels contemporary Britain: flashes of former glory followed by a bewildering inability to execute basic tasks. And the bullpen? Pure United Nations peacekeeping: well-intentioned, tragically underfunded, and ultimately powerless to stop the slaughter. When closer Edwin Díaz tore his knee during a World Baseball Classic celebration, the symbolism was almost insultingly on-the-nose: injured while dancing for someone else’s flag.

Yet the cruelty of baseball—and perhaps of history—is that hope persists in inverse proportion to evidence. Every August, when the Mets are mathematically eliminated but mathematically alive in the Wild Card because the league insists on rewarding mediocrity (an innovation the G-20 is studying carefully), the fans return. They chant, they boo, they hope. It is the same hope that keeps Greeks paying taxes, or that persuades Argentine voters that this new peso will surely hold. Call it the human condition, wrapped in a $12 hot dog.

So, as trade winds swirl and the Mets shop veterans for prospects who will one day become veterans to be shopped again, the world watches with the morbid curiosity reserved for slow-motion train wrecks that double as cultural artifacts. Somewhere in Beijing, a strategist updates a PowerPoint titled “Indicators of American Decline.” Slide 17: Mets payroll-to-wins ratio, 2023-24. The conclusion is elegant, devastating, and already translated into five languages: even the house with the biggest chips can bust.

And yet, tomorrow, first pitch is at 7:10. The empire may be fraying, but the concession stands still take Apple Pay.