Jerry Jones: How One Texan Became the NFL’s Last Global Monarch

Jerry Jones: The Last American Monarch in a League of His Own

By Our Man in Row Z, International Affairs Desk

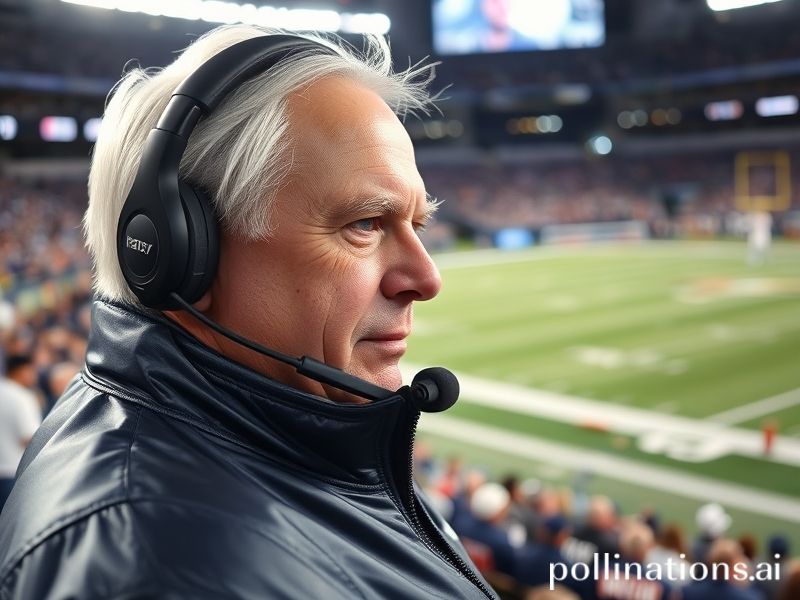

The name “Jerry Jones” doesn’t translate into Mandarin or Swahili, yet from Lagos sports bars to Seoul betting apps, everyone knows the silhouette: the silver pompadour rising from a luxury box like a weather balloon of wounded vanity, surveying the empire of the Dallas Cowboys as if Caesar had just discovered end-zone sponsorship. Jones is not merely an NFL owner; he is a geopolitical singularity—proof that in the 21st century you can still purchase a city-state provided it plays on Sundays and sells foam fingers.

From a distance, the phenomenon looks absurd. Uruguayans who can’t name their own president can recite the Cowboys’ 1995 Super Bowl roster; Filipino call-center agents wear star-shaped decals while upselling AT&T plans. The franchise’s estimated $9 billion valuation now exceeds the GDP of Sierra Leone, a fact Jones repeats with the same paternal pride he once used to describe a well-executed screen pass. In effect, one man’s midlife crisis became an export commodity more durable than American democracy.

Jones’s international significance lies precisely in how he weaponizes nostalgia. While Europe exports Renaissance paintings and Japan exports bullet trains, the United States exports the 1970s in shoulder pads: a sepia-toned myth of cowboy individualism wrapped in corporate synergy. The Cowboys’ cheerleaders tour U.S. military bases from Ramstein to Okinawa, a soft-power burlesque that reassures troops the empire still has cleavage and a theme song. Meanwhile, the man bankrolling the choreography spends his off-seasons lobbying Washington to keep antitrust laws as flaccid as a pre-season hamstring.

The darker punchline is that Jones’s business model—maximize revenue, externalize risk—has gone viral. Manchester United’s Glazer family borrowed it; Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund downloaded the PDF. When the Kingdom announced its LIV golf rebellion, the template was pure Jones: buy legends, flood the zone with cash, dare regulators to blink first. The difference is the Saudis execute dissidents, whereas Jerry merely trades them to Cincinnati. Both, however, understand that in the attention economy, moral stature is just another luxury suite: nice if you can afford it, irrelevant if you can’t.

Back home, Jones plays the folksy oligarch, the billionaire who still answers his own flip phone (a detail repeated so often it may soon qualify as performance art). Yet the international audience sees the grimmer calculus. While European soccer clubs flirt with salary caps, Jones has pioneered the art of turning civic identity into a subscription service. Every $400 ticket, every $16 beer, every taxpayer-funded stadium upgrade is a micro-transfer from the communal wallet to the offshore account. It’s privatized nationalism: fans pledge allegiance to a logo that pays no taxes in its own hometown.

Still, one must admire the purity of the hustle. In a world where glaciers file for bankruptcy and democracies auction themselves to the highest bidder, Jones offers a rare honesty: everything, including tradition, is for sale. The Cowboys may not win playoff games—one Lombardi Trophy since 1996 is a return rate that would shame a slot machine—but they win quarterly earnings with ruthless consistency. That, ultimately, is the global takeaway: victory is obsolete; valuation is eternal.

So as another season kicks off beneath retractable roofs and drone-cam glory, remember that from Nairobi to Naples, the star on that helmet functions as an imperial crest. Jerry Jones isn’t just selling football; he’s selling the last unifying story America has left—one that says you too can fail upward forever, provided you own the narrative, the stadium, and the referees. The rest of us? We’re just extras in the commercial break, clutching overpriced merchandise and pretending the score still matters.