Nationwide Building Society: The Last Coelacanth of Global Finance Refuses to Evolve

Nationwide Building Society: The Last Great British Mutual Standing, or Just the Slowest to Fall?

LONDON—From a safe distance—say, a rooftop bar in Singapore, a co-working bunker in Berlin, or a tax-efficient villa in Dubai—Nationwide Building Society can look almost quaint. A 175-year-old British institution that still calls itself a “mutual,” as if the word hadn’t been strip-mined by every crypto-cult and multi-level marketing scheme on the planet. While the rest of the world races to tokenise the air we breathe, Nationwide insists on being owned by its customers, a business model as fashionable as a dial-up modem and about as profitable, according to certain hedge-fund palm trees swaying in the Caymans.

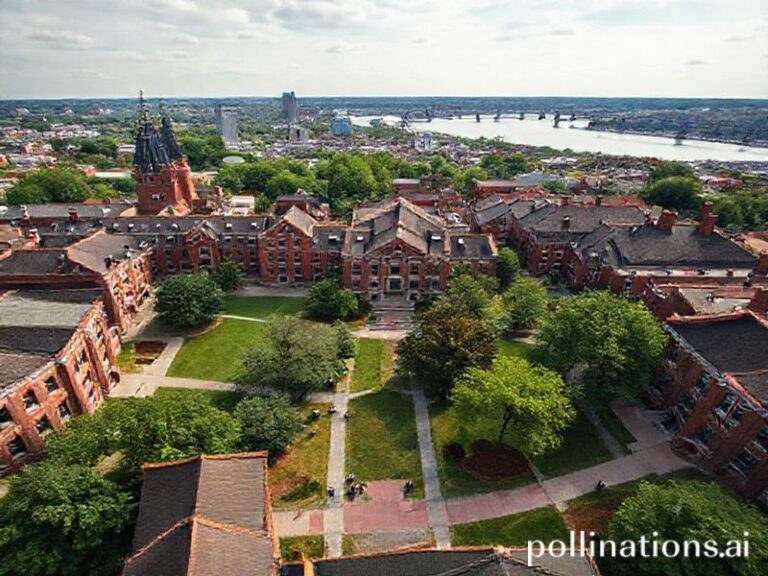

But peer closer and the quaintness curdles into something darker. Nationwide is the financial equivalent of that last Victorian pier left standing after a hurricane: photogenic, yes, but mainly because everything else has been washed out to sea. In global terms, the society’s £272 billion in assets barely registers against, say, JPMorgan’s $3.9 trillion or the Bank of Japan’s collection of ETFs that now includes a small planet of corporate Japan. Yet size misses the point. Nationwide matters precisely because it refuses to scale according to the orthodox gospel of eat-or-be-eaten. It is a living fossil, a coelacanth in a bespoke suit, swimming through an ocean increasingly acidified by fintech unicorn flatulence.

Consider the international context. Across Europe, cooperative banks have been merging themselves into unpronounceable megaclusters or quietly slipping nationalisation notes under the door. In the United States, credit unions survive by acting like banks but with better Christmas parties. Meanwhile China’s “mutuals” have the delightful habit of turning into Ponzi schemes the size of provincial GDPs. Against this backdrop, Nationwide’s mere continued existence feels like an act of sedition—proof that somewhere, somehow, a financial institution can still prioritise a rainy-day fund over a shareholder dividend large enough to buy a medium-sized yacht.

Of course, even mutuality has its price. Nationwide’s 2023 decision to shutter 143 branches—roughly 20% of its network—was met with the usual orchestrated outrage: tabloids thundering about “heartless” closures, MPs discovering rural broadband for the first time, pensioners waving placards that read “Hands Off Our Cash.” (As if cash weren’t already being shoved into extinction by every tap-and-go evangelist with a venture-capital sugar-daddy.) The closures, we were told, were merely “responding to changing customer behaviour,” which is corporate-ese for “we finally ran the numbers and discovered people prefer not to queue next to a mouldy carpet just to check if their ISA matured.”

The global lesson here is bleakly comic. Every regulator from Brussels to Basel now preaches “digital inclusion,” while simultaneously presiding over the demolition of the last physical outposts where inclusion might actually happen. The World Bank loves to lecture emerging markets about branchless banking, yet seems puzzled when rural Kenyans still trek kilometres to find a signal strong enough to access M-Pesa. In that sense, Nationwide’s retreat is simply the developed world catching up to the contradictions it exports abroad: first we build cathedrals of commerce, then we burn them down and call it innovation.

Still, there is something perversely heroic in the society’s refusal to demutualise. Three times in the past 25 years the vultures circled, promising instant windfalls if only members would vote to float on the stock market. Three times the members shrugged, presumably calculating that a one-off cheque is poor compensation for a lifetime of slightly less predatory overdraft fees. It’s the financial equivalent of turning down a Tinder date who promises to pay for dinner but definitely expects the night to end in derivatives.

Where does this leave the wider world? Perhaps nowhere. Or perhaps with a reminder that capitalism’s most subversive act is occasionally not to maximise profit, but to decline the opportunity. In an era when every app on your phone wants to own your soul, Nationwide’s continued mutual status is less a business strategy and more a dark joke: the last bank in Britain that still works for the people who bank there, and not the other way around.

For now, the coelacanth swims on, oblivious to extinction timelines and venture-capital harpoons. Enjoy the view while you can; evolution is rarely this polite for long.