Swansea’s Global Splash: How Welsh Floods Became Everyone’s Problem

**Swansea’s Soggy Rebellion: When the Sea Knocks on Wales’ Door (Again)**

By the time the River Tawe had finished redecorating Swansea city centre—rust-coloured water lapping against kebab-shop menus and half-submerged bus shelters—local councillors were already promising “world-class flood resilience” to anyone who still owned a pair of dry shoes. Translation: another round of PowerPoint presentations and a politely-worded e-mail to Westminster that will be filed somewhere between “fix the NHS” and “find a prime minister who lasts longer than a lettuce.”

From a global vantage point, the latest inundation of this former copper-smelting powerhouse is less a provincial mishap and more a postcard from the front line of civilisation’s half-hearted wrestling match with climate change. Swansea, population 245 000, has become an unlikely exhibit in a planetary museum of hydro-logical slapstick: a place where medieval drainage meets 21st-century rainfall, and neither of them is prepared to budge.

The numbers are almost cute—if your sense of humour survived 2020 intact. Up to 150 mm of rain in 48 hours, about the same volume London receives in an entire November, dumped itself on south-west Wales with the enthusiasm of a tourist who’s discovered free refills. Insurance companies, those paragons of human empathy, immediately dispatched loss adjusters armed with clipboards, waterproof drones, and the glazed optimism of people who know premiums are about to rise faster than the water did.

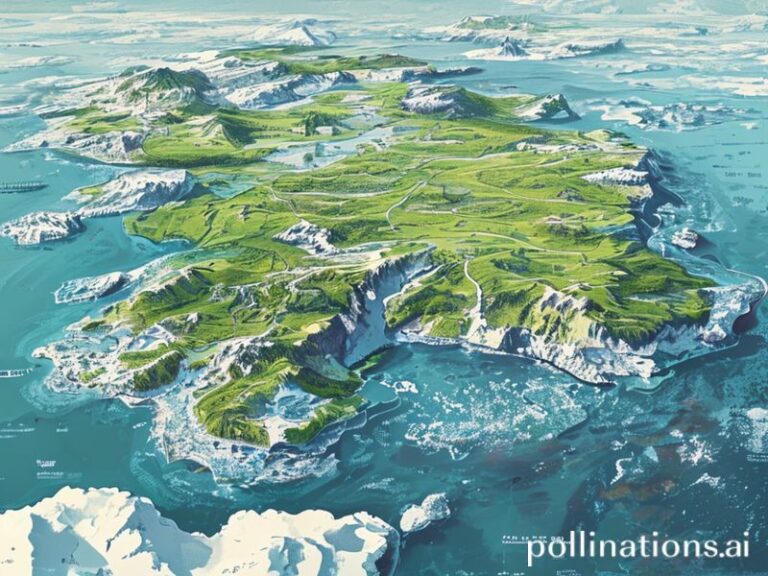

But let’s zoom out, shall we? Satellite images don’t care about national borders; they show a brown, braided ribbon of sediment bleeding into the Bristol Channel, eventually mingling with the Atlantic, where it will wave hello to storm-battered Florida, cyclone-weary Fiji, and any other postcard destination that still advertises “sun-kissed beaches” instead of “partially submerged, bring flippers.” The same North Atlantic jet stream that wheeled Storm Bert (yes, we’re naming them like Disney sidekicks now) across Wales is the atmospheric conveyor belt currently icing New England and flash-freezing Alpine ski resorts. One airstream, multiple PR disasters.

Internationally, Swansea’s soggy carpets reverberate in boardrooms from Zurich to Singapore. Re-insurers have taken to hiring climatologists the way Renaissance popes hired painters—except the ceiling being frescoed is actuarial tables, and the paint is increasingly red. Moody’s, the credit-rating agency that treats entire countries like moody teenagers, has already warned that “flood-prone regions without adaptive infrastructure” face downgrades. Translation: if your storm drains were designed during the reign of Queen Victoria, your municipal bonds will soon trade like Venezuelan cryptocurrency.

Meanwhile, in the geopolitical classroom, floods are the new field trips. Chinese engineers specialising in sponge-city technology—concrete that drinks rainwater the way undergraduates drink cheap lager—have been flown in to consult, because nothing says “global Britain” like inviting the world’s largest emitter to teach you how to cope with the consequences of, well, emissions. American FEMA officials, fresh from yet another “once-in-a-lifetime” deluge in Kentucky, offered advice on buy-back schemes: essentially paying people to abandon houses nobody should have built in the first place, a programme economists call “strategic retreat” and homeowners call “please ruin my credit rating more gently.”

And yet, human nature remains gloriously incorrigible. Estate agents (realtors for the monolingual) have already rebranded the most affected streets as “waterfront-adjacent” and slapped 10 % on asking prices. A local pub, three feet deep in murky runoff, advertised “free pint if you bring your own canoe,” thereby inventing the world’s first amphibious happy hour. Someone started a TikTok channel called “Swansea Baywatch,” featuring inflatable unicorns drifting past half-submerged speed cameras. It went viral, obviously.

The broader significance? Swansea is what happens when the Anthropocene signs the guestbook. The city’s very name derives from Old Norse “Sweyn’s ey,” an island—already a hint that dry ground here was always negotiable. Industrial revolutionaries later paved over tidal marshes with the same breezy confidence they brought to child labour. Today, the bill arrives with compound interest, denominated in cubic metres and YouTube outrage.

If there is a moral, it’s that geography is a patient accountant. You can ignore the ledger, rebrand the liabilities, elect governments who promise to “level up” gravity itself, but eventually the water collects its rent. And unlike politicians, water always serves a full term.

So here’s to Swansea, latest contestant in the planetary game show *Sink or Subsidise*. May your wellies stay watertight, your internet connection remain above the high-tide mark, and your sense of humour float long after the sofas have gone under. The rest of the world is watching—partly in sympathy, mostly because we’re next.