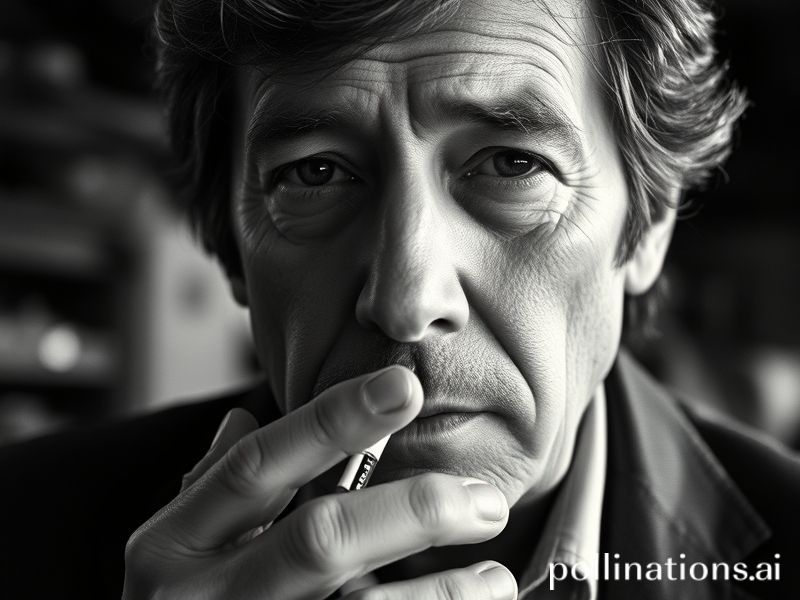

Dustin Hoffman: How a Nervous New Yorker Became the Planet’s Shared Anxiety Disorder

Dustin Hoffman: The Accidental Everyman Who Conquered a Planet That Barely Agreed on Anything

By Our Man in the Cheap Seats, Watching the World Burn in Subtitles

PARIS—Try explaining Dustin Hoffman to a Gen-Z Berliner who thinks “The Graduate” is a crypto-scam and “Rain Man” a TikTok filter. You’ll discover, as I did over flat beers in Kreuzberg, that Hoffman’s 60-year career functions like a Rorschach test for whatever fresh hell the globe is currently enduring. Show a Ukrainian film student “Little Big Man” (1970) and he sees an occupied nation’s guerrilla farce. Screen “Wag the Dog” (1997) in Buenos Aires during yet another peso nosedive and the audience howls at the fake-war newsreel as if it were last night’s cable bulletin. The man is a human diplomatic pouch: smuggling uncomfortable truths across borders disguised as entertainment.

Hoffman never meant to be universal. A short, nasal New Yorker with the physique of a worried librarian, he debuted when leading men still looked like vacation real-estate—broad balconies and square jawlines. Then came 1967, the Summer of Love, race riots, and a million American kids rehearsing jungle deaths in advance. Into that bonfire sauntered Benjamin Braddock, Hoffman’s signature graduate, floating in a backyard pool while society asked him to plastics. Overnight, every disaffected teenager from Rotterdam to Rio could quote “Mrs. Robinson” in the original disillusionment. The film grossed more in 1968 Tokyo than in Chicago, proving angst exported better than Coca-Cola and didn’t need ice.

By the time he filmed “Midnight Cowboy” (1969) on rat-infested 42nd Street, the planet had upgraded its misery to Technicolor. The movie’s X rating—earned not by porn but by the crime of being depressing—still snuck past censors in Franco’s Spain and Brezhnev’s Moscow. Bootleg VHS tapes circulated like samizdat; dissidents reported that watching Ratso Rizzo cough his lungs out made their own shortages feel almost cinematic. Nothing bonds strangers faster than shared respiratory despair.

The Eighties found Hoffman method-acting his way into a woman’s heels for “Tootsie” (1982) while the world practiced nuclear-war drills. The film played in Bangkok malls where Thai drag queens discovered a Hollywood star validating their nightly hustle against junta morality codes. Simultaneously, American cineplex-goers laughed off the possibility that gender might be performance art; three decades later most of them still can’t decide which bathroom to use, but the receipts don’t lie—$177 million back when that could buy an aircraft carrier or two.

Then came “Rain Man” (1988), the high-water mark of global autism awareness and airline-safety anxiety. Suddenly every securities trader in London pretended to count cards, and Korean medical schools reported record applications. Hoffman’s Oscar was shipped FedEx to a man who reportedly keeps it in the bathroom so guests can practice their best Raymond Babbitt monotone while washing hands—hygiene theatre before it was fashionable.

The actor’s later act has been quieter, the roles smaller, the world louder. He stole “The Meyerowitz Stories” (2017) as a cantankerous sculptor, a performance that hit harder in Seoul, where inheritance lawsuits are practically a national sport, than in his native Los Angeles. Meanwhile, #MeToo floated 1980s allegations that he groped a 17-year-old intern on set—proof that even ambassadors of empathy carry expired visas. Hoffman apologized “if,” the conditional tense beloved by politicians and divorced dads. International audiences split along predictable fault lines: Americans canceled, the French shrugged, Indians asked for video evidence, and the BBC ran a explainer titled “What Is Groping?” Cultural diffusion at its finest.

What keeps him relevant is the same flaw that made him famous: he looks like the guy who would steal your cab, not your heart. In an age of airbrushed influencers and strongman presidents, Hoffman’s arsenal of twitches, stammers, and moral panic feels almost documentary. The planet keeps manufacturing new anxieties—climate, TikTok, oligarchs, algorithms that know you want divorce lawyers before you do—and Hoffman keeps anticipating them like a Jewish Cassandra with better comic timing.

So raise a glass, comrades, to the accidental everyman: a five-foot-six reminder that globalization isn’t just container ships and spyware; it’s also shared nightmares projected 24 frames per second. Somewhere tonight, a Colombian teenager streams “All the President’s Men” on a cracked phone and decides maybe journalism beats dealing cocaine. That’s soft power, Hoffman-style—less aircraft carrier, more nervous cough heard round the world. And when the last cinema collapses into a Starbucks, you’ll still find his face buffering on a refugee’s cracked screen, asking whether we’re trying to seduce each other or just drowning together, one plastic at a time.