Global Timeout: How Padres vs Mets Became the Planet’s 3-Hour Peace Treaty

Padres vs Mets: The World Watches Two Cities Fight Over a Piece of Leather Like It’s 1492

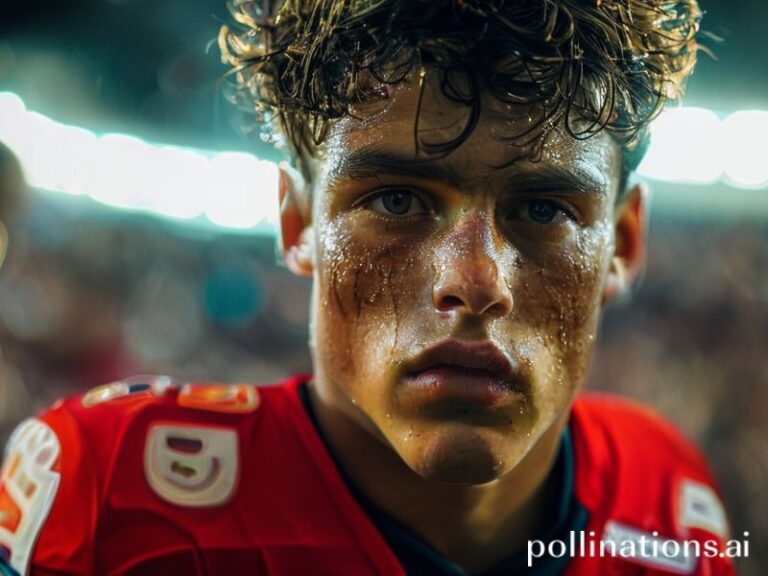

From the rooftop cafés of Istanbul to the fluorescent-lit call centers of Manila, humanity took a synchronized coffee break Wednesday night to tune in to a ceremonial duel between San Diego and New York. On the surface, it was merely a baseball game—San Diego Padres versus New York Mets, NLCS Game 3, extra innings, enough statistical arcana to make a Swiss banker blush. In reality, it was the planet’s latest proof that we will happily obsess over anything, provided it distracts us from the carbon readings, the supply-chain snarls, and the slow-motion implosion of the post-war order.

Let’s zoom out. In Kyiv, air-raid sirens formed an accidental harmony with the seventh-inning stretch; in São Paulo, traders on the B3 exchange kept one eye on the peso-real spread, the other on a lagging MLB.TV stream. Even the Chinese firewall, normally as forgiving as a Swiss bouncer, let VPN traffic spike just long enough for 4.2 million users to watch Pete Alonso swing and miss like a man trying to swat a philosophical concept. The global economy may be held together with duct tape and central-bank hallucinations, but we still find time to argue about whether a 97-mph fastball is more democratic than a slider thrown by a man who looks like he’s been sculpted from Guatemalan volcanic ash.

The geopolitical stakes, one must admit, are absurdly low. Neither the Padres nor the Mets have any bearing on grain exports through the Black Sea, nor will the outcome tweak the yield on two-year Treasuries. And yet, state broadcasters from Al Jazeera to the BBC carved out precious minutes to dissect whether the ghost of Steve Cohen’s hedge-fund billions could purchase a clutch hit. Viewers in Nairobi bars groaned in unison when the Padres’ bullpen coughed up the lead, a universal language of disappointment that needs no subtitles.

San Diego, that sun-bleached monument to architectural amnesia, styles itself as America’s polite afterthought. New York, meanwhile, is the city that never sleeps because it’s too busy filing noise complaints against itself. Between them lies a cultural fault line as old as NATO: the laid-back Pacific versus the neurotic Atlantic, avocado toast versus dollar-slice existentialism. The irony, of course, is that both rosters are international patchworks—Dominicans, Venezuelans, a Japanese closer who looks like he meditates on the concept of strikeouts. The fans wave flags they barely understand, chanting in Spanglish, proving that globalization works best when no one stops to read the instruction manual.

Back on the diamond, the game stretched into the twelfth inning, which is roughly when casual spectators in Warsaw began checking artillery reports and hardcore fans in Melbourne started inventing new expletives. Each foul ball became a metaphor for our collective inability to finish anything—climate accords, peace treaties, that sourdough starter from 2020. When Trent Grisham finally laced a two-run double, the eruption in Petco Park registered on seismographs usually reserved for tectonic gossip. Somewhere in a Geneva think tank, an intern updated a spreadsheet titled “Global Emotional Volatility Index,” color-coded in Padres brown.

The Mets, ever the tragic opera of Major League Baseball, boarded their charter afterward looking like a team that had just audited its own soul. Manager Buck Showalter muttered about missed opportunities with the weary cadence of a man who has read too many UN climate reports. Across the runway, the Padres popped champagne that cost more per ounce than the average Bangladeshi monthly wage, proving that Keynes was only half right: in the long run we are all dead, but in the medium run we are all indebted to a relief pitcher from Culiacán.

Conclusion? Somewhere between the first pitch and the final out, eight billion people agreed—without ever voting—to suspend disbelief for three hours and forty-one minutes. The final score will be forgotten by next fiscal quarter, but the temporary truce it brokered among disparate, anxious populations may be the closest thing to world peace we can still manufacture on demand. And if that’s not worth a standing ovation, turn the page and enjoy the next apocalypse.