How Robert Munsch Accidentally Became the World’s Most Effective Diplomat: The Subversive Global Legacy of a Canadian Storyteller

**The Paper Bag Princess Goes to Gaza: How Robert Munsch Accidentally Became the World’s Most Subversive Diplomat**

While diplomats in Geneva negotiate ceasefires over canapés, a Canadian children’s author has achieved what the United Nations never could: teaching generations of kids that princes are often useless, dragons can be outwitted by clever girls, and love frequently ends in mutual disappointment. Robert Munsch—who passed away earlier this year at 78—never intended to become an accidental revolutionary, but his stories have done more to shape international childhood development than most foreign policy initiatives.

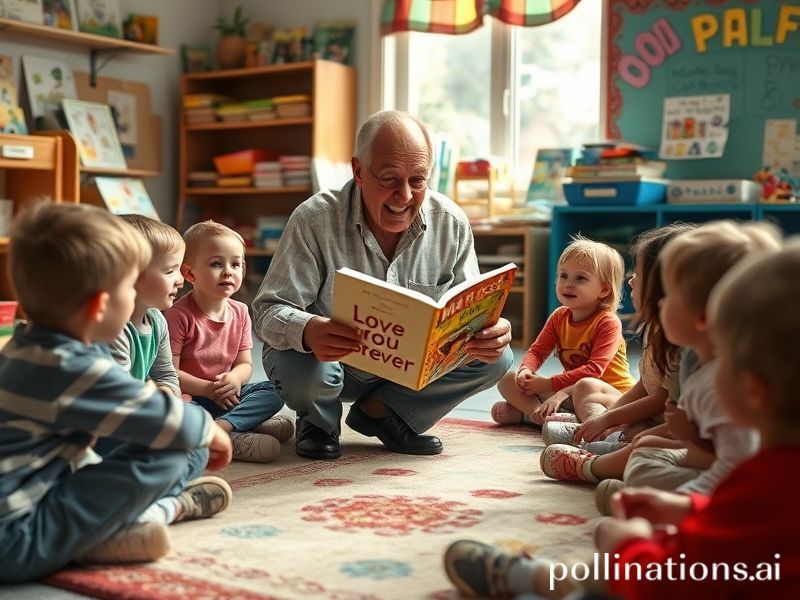

The irony, of course, is delicious. Here was a man who struggled with addiction and mental health issues, telling bedtime stories that would fundamentally alter how children worldwide understand power dynamics. “Love You Forever”—that creepy stalker anthem about a mother who breaks into her adult son’s house—has been translated into over 30 languages, ensuring that children from Tokyo to Timbuktu learn that boundaries are optional and helicopter parenting transcends cultural barriers.

But it’s “The Paper Bag Princess” that cemented Munsch’s status as an unwitting geopolitical force. Published in 1980, this tale of a princess who rescues her ungrateful prince while wearing nothing but a paper bag has become required reading in progressive schools from Stockholm to Singapore. The story’s message—that women don’t need saving and princes are often disappointing—has somehow managed to offend traditionalists across every continent. Saudi Arabia banned it briefly, which is rich coming from a country where women couldn’t drive until 2018. Even Putin’s Russia has given it the side-eye, presumably because teaching girls to think independently interferes with their gymnastics training.

The global reach of Munsch’s work reveals something profoundly depressing about our species: we’ve somehow reached 2024 and still need children’s books to explain that women are people. His stories have become stealth weapons in the culture wars, smuggled across borders like intellectual contraband. In rural India, NGOs use “The Paper Bag Princess” to teach girls about gender equality. In South American orphanages, his tales provide templates for processing trauma through narrative—a psychological hack that costs less than therapy and comes with amusing illustrations.

What’s particularly galling is how Munsch’s simple formula—ordinary kids facing extraordinary challenges with wit and determination—has proven more effective at building resilience than billion-dollar international aid programs. While the World Bank funds elaborate childhood development initiatives, a used copy of “I Have To Go!” (the one about bathroom emergencies) teaches kids more about bodily autonomy than most government health campaigns.

The author himself seemed bemused by his accidental empire. A former preschool teacher who discovered storytelling while high on LSD—because of course he did—Munsch understood that children are essentially tiny anarchists who see through adult hypocrisy. His stories work because they acknowledge what international relations experts refuse to admit: most systems are arbitrary, authority figures are frequently wrong, and the real solutions come from unexpected places.

As the world becomes increasingly authoritarian and various strongmen try to drag us back to some mythical golden age, Munsch’s subversive little paperbacks continue circulating through tiny hands worldwide. Each generation discovers anew that dragons can be defeated not through force, but through intelligence and a healthy disrespect for conventional wisdom. In an era where actual princesses still exist and somehow maintain relevance despite contributing nothing to society, teaching children that royalty is optional feels almost treasonous.

Perhaps that’s Munsch’s greatest legacy: creating stories so fundamentally honest about human nature that they transcend borders, languages, and cultural barriers. While adults continue their endless, futile negotiations over territory and resources, children worldwide are learning that the real battles are fought in playgrounds and bedrooms, and victory often belongs to whoever tells the best story.

The dragons, it seems, were never the real problem.