Global Hangover: How the House of Guinness Became the World’s Most Intoxicating Metaphor

Somewhere between Dublin’s Liffey and Lagos’s Third Mainland Bridge, the phrase “House of Guinness” now carries a weight heavier than its original 1759 gravity. Once a humble brewery scribbled on parchment by Arthur Guinness—who, legend insists, signed a 9,000-year lease because even then the Irish hedged against Brexit—the name has metastasized into a multinational metaphor for how colonial hangovers, marketing sorcery, and global capitalism can ferment in the same vat. Today, the House of Guinness is less a brick-and-mortar landmark than a movable feast of contradictions, sloshing across time zones and tax havens with the confident swagger of a man who knows his stout is 4.2% ABV but his brand is 100% proof.

Start with Africa, where Guinness Foreign Extra Stout—bottled at 7.5% ABV, presumably because life on the continent already feels like an accelerated intoxicant—outsells Budweiser, Heineken, and the concept of sobriety combined. In Nigeria, the brand is so embedded in the national psyche that wedding dowries occasionally include a symbolic crate of Guinness, presumably to ensure the groom can still stand after paying bride-price inflation. In Ghana, billboards show the black stuff cascading beside slogans about “Black Shines Brightest,” a phrase that would be uplifting if it weren’t also the exact wording a 19th-century colonial officer might have used while polishing his boots. Meanwhile, Diageo—Guinness’s parent company and the world’s largest purveyor of “premium” liver damage—quietly routes profits through the Netherlands to keep excise duties light and consciences lighter.

Swing over to Southeast Asia and you’ll find Guinness thriving in Muslim-majority Malaysia, where sharia law frowns on the product but not on the tax revenue it generates. The local brewery in Sungai Way produces a halal-compliant malt drink that tastes like Guinness’s teetotal cousin, while the real thing is imported duty-free for non-Muslims and expats nostalgic for colonial clubhouses. It’s the sort of arrangement that makes you wonder whether God or the Inland Revenue Board is harder to please.

Back in Europe, the original St. James’s Gate brewery has been retrofitted into a Willy Wonka factory for adults who prefer ethanol to chocolate. Tourists pay €25 to learn that Guinness is “good for you,” a claim originally made in 1920s advertisements next to doctors in white coats who now look suspiciously like the same actors hired by Big Tobacco. The gift shop sells €40 rugby shirts stitched in Bangladesh, allowing fans to celebrate Irishness while outsourcing its sweatshops. Brexit, naturally, has only made the pilgrimage stranger: British visitors queue for hours to enter what is technically a foreign country, then complain about the “import duty” on their souvenir pint glasses.

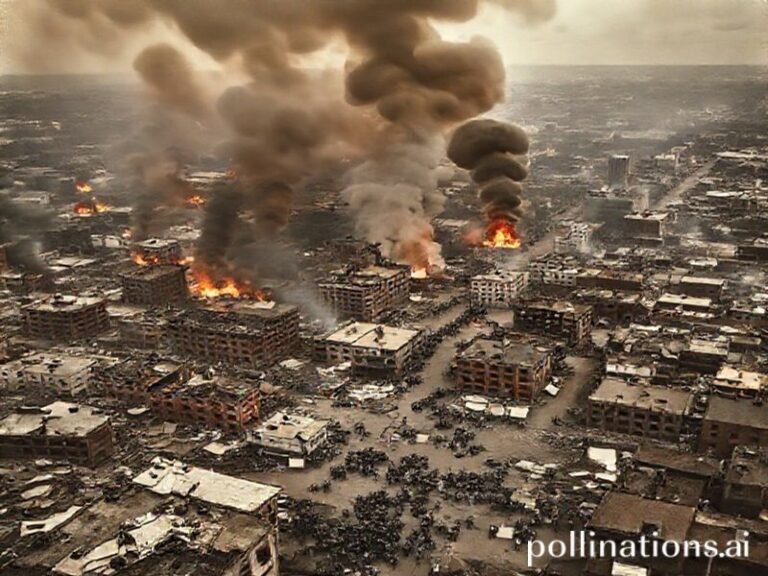

And then there is the digital House of Guinness, a sprawling online empire where influencers in Jakarta pose with nitro cans against neon backdrops, hashtagging #StoutLife while their governments scramble to regulate influencer alcohol ads aimed at teenagers who can’t legally drink. Somewhere in Silicon Valley, an algorithm notes that users who post Guinness also linger on cryptocurrency scams and apocalypse prep kits, data that will eventually be sold back to Diageo so they can market a “Limited Edition End-of-World Stout” aged in ex-bourbon barrels once destined for doomsday bunkers.

What does it all mean? Simply that the House of Guinness is no longer bound by geography, gravity, or good taste. It is a liquid passport, a frothy palimpsest of empire, aspiration, and the human desire to both belong and numb the belonging. Arthur Guinness’s 9,000-year lease suddenly looks optimistic; at current rates of consumption and climate change, we’ll either run out of barley or breathable air long before then. Until that day, the black stuff will keep circulating, a dark mirror held up to a world that insists on celebrating its contradictions one pint at a time. Sláinte—or as they say in Lagos, “Bottoms up before the generator runs out.”