How One Chair Conquered the Planet: The Global Empire of a Simple Seat

The Chair Company That’s Sitting on the World

By “Correspondent-at-Large with Chronic Back Pain”

GENEVA—Somewhere between the fifteenth espresso of the week and the forty-seventh UN resolution on sustainable furniture, it became clear that the world’s most powerful seat of power is, quite literally, a seat. The Chair Company—officially known as Sedis Universalis S.A., though its logo is now more recognizable than the Swiss flag—has spent the last decade quietly colonizing the planet’s backside. From Lagos boardrooms to Reykjavik startups, from Kremlin war rooms to your cousin’s yoga-coworking-pod in Bali, the identical curved silhouette of the “Model Ø” has become the lingua franca of modern derrieres.

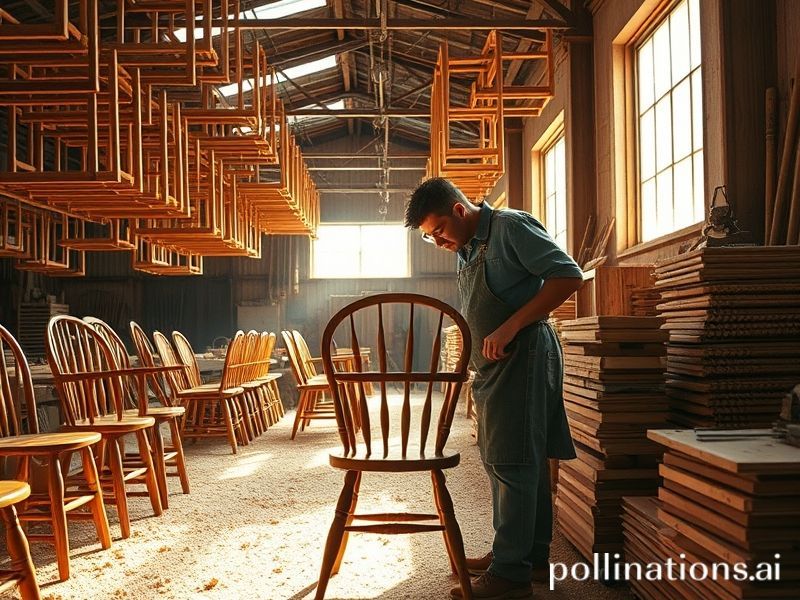

How did a purveyor of molded polypropylene conquer the globe? The same way Rome did: roads, logistics, and an almost erotic obsession with infrastructure—only this time the roads are container ships and the legions are brand consultants. Sedis Universalis perfected the flat-pack algorithm so ruthlessly that IKEA now looks like a Swedish folk museum. One 40-foot container can carry 2,048 disassembled chairs, or, as the shipping manifest dryly notes, “enough seating to stage a coup in a midsize republic.” That efficiency has allowed the Chair Company to undercut local artisans from Oaxaca to Ouagadougou, reducing centuries of woodworking heritage to a QR code on the side of a box.

The geopolitics of sitting are not taught in schools, which is a shame, because the Model Ø is now the unofficial throne of every provisional government, Silicon Valley IPO, and Zoom tribunal. When the generals in Myanmar needed a backdrop that whispered “we’re open for business,” they ordered 300 units in matte black. When the World Economic Forum convened last January, Klaus Schwauz himself perched on a custom snow-white edition with extra lumbar support—rumored to be upholstered in the recycled promises of 2009’s climate accords.

Of course, no empire comes without collateral discomfort. Vietnamese factory workers report that the polypropylene fumes give dreams the color of antifreeze; Scandinavian designers sue over “aesthetic plagiarism,” arguing the curve of the Ø is mathematically identical to a fjord they sketched in 1997. Meanwhile, supply-chain theologians calculate that if every Model Ø currently in transit were stacked seat-to-seat, the tower would graze the Kármán line—an ironic monument to humanity’s desire to get off its feet and still never leave Earth.

The marketing, meanwhile, is a masterclass in planetary gaslighting. Sedis Universalis advertises the Ø as “democratic seating,” which sounds uplifting until you realize they mean it in the Athenian sense: one citizen, one cheek. Their newest campaign—shot in the Azores, because nothing screams sustainability like volcanic islands—features diverse millennials planting trees between takes while seated on the very petroleum product that funded the flight. Tagline: “Sit for the Future.” Comment sections have already Photoshopped the slogan onto images of melting ice caps; the company responds by pledging to offset each chair with a sapling, a promise roughly as binding as a UN press release.

Still, resistance remains seated, if not entirely comfortable. Activists in Mexico City have begun retrofitting vintage equipales with USB chargers, branding them “Slow Chairs” for those who prefer their furniture without existential dread. Berlin squatters host “stand-up meetings” that last until someone collapses, just to spite the Ø. And in a particularly savage act of performance art, a collective in Lagos floated 500 knockoff chairs down the Niger River, filming them like refugees until they clogged the port at Bonny—an aquatic traffic jam of plastic aspiration.

Yet the numbers recline inexorably upward: 42 million units sold last fiscal year, penetration in 143 countries, and a projected IPO valuing Sedis Universalis somewhere between New Zealand and Jeff Bezos’ divorce settlement. Analysts argue the brand’s true genius is not the chair but the void it fills: a globally legible symbol of modernity, cheaper than ideology and less painful than standing for anything.

So the world spins on, its weight distributed evenly across 42 million identical seats, each one whispering the same ergonomic promise: you may not know where you’re going, but at least your lumbar region will arrive intact. And when the last glacier calves into the sea, historians will note that humanity faced its final crisis dutifully seated—calm, productive, slightly hunched, and utterly unable to get up.