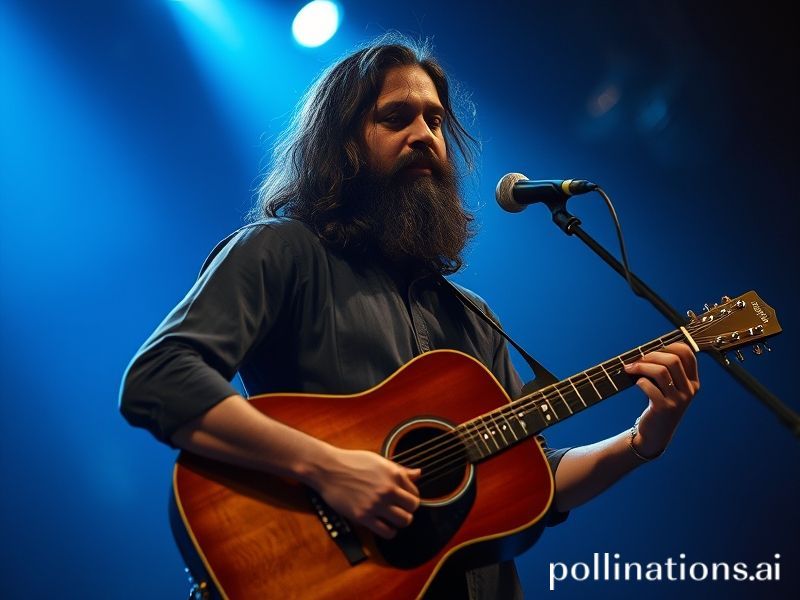

Zubeen Garg: How a Balladeer From Assam Quietly Conquered the World Without a Single English Chorus

The Ballad of Zubeen Garg, or How One Man From Assam Accidentally Became a Pan-Asian Soft Power Weapon

By Our Man in Guwahati, Nursing His Third Kingfisher of the Morning

Guwahati, Assam – While the rest of the planet obsesses over whether Taylor Swift’s carbon footprint can be offset by planting a forest the size of Luxembourg, 5,000 kilometres east of Nashville another singer-songwriter has been waging a stealth campaign for global domination. His name is Zubeen Garg, he owns approximately 37,000 songs (or so the local papers claim when they run out of corruption scandals), and he has pulled off the rare trick of being both hyper-local and inexplicably exportable—like kimchi-flavoured craft beer.

Zubeen began life, as most of us do, small and crying, but by 13 he had already recorded an album in Assamese, a language spoken by roughly the same number of people who watched that last Snyder Cut trailer. Fast-forward three decades and the man has become a living, lung-powered refutation of the idea that only English can travel. His songs—mostly in Assamese, Bengali, and Hindi—now leak out of autorickshaws from Dhaka to Dubai, proving that melodic melancholy needs no subtitles. Spotify lists him under “World,” a category so vague it could also contain Mongolian throat metal or your uncle’s snoring.

The international significance? Start with soft power, that bloodless euphemism for cultural seduction. New Delhi has spent billions on yoga embassies and “Incredible India” ads starring bewildered Instagram couples, yet a single Zubeen track played at 2 a.m. in a Bangkok nightclub apparently does more for Brand India than an entire season of diplomacy. Thai teenagers who can’t spell Assam now mumble phonetic Assamese choruses between sips of bubble tea. Somewhere in the Ministry of External Affairs, a mid-level bureaucrat is taking credit.

Meanwhile, the Bangladeshi border—often a theatre of cattle smuggling and existential dread—has become a low-key Zubeen corridor. Bootleg USB drives, each crammed with 500 songs and a suspicious .exe file, cross the river Brahmaputra like harmonic contraband. Customs officers, demoralised by the futility of seizing narcotics and fake iPhones, wave the drives through; you can’t tax homesickness, and you definitely can’t confiscate a chorus that’s already stuck in your head.

Economists will tell you culture is the new oil, except the wells never run dry and nobody has to invade anything—perfect for a climate-anxious century. Zubeen’s multilingual karaoke empire therefore becomes a case study in frictionless globalisation: zero sanctions, minimal carbon, maximum earworm. If the WTO ever figures out how to slap tariffs on nostalgia, we’re all doomed.

Naturally, there is a darker subplot. Fame on the subcontinent is a contact sport; fans here treat pop stars the way Renaissance Italians treated the Borgias—simultaneous reverence and menace. Zubeen has survived everything from stage stampedes to the occasional death threat over lyrics allegedly disrespectful toward local deities. After one particularly spirited concert in 2018, a rumour spread that he’d been abducted by ULFA militants. He turned up the next day at a dhaba eating pork thali, mildly annoyed that the kidnappers hadn’t bothered to tune his guitar while he was gone.

Covid, that great equaliser, only accelerated his reach. Trapped indoors, the global diaspora turned to YouTube rabbit holes, and Zubeen—bearded, barefoot, crooning about monsoon love—became their algorithmic comfort blanket. Streams tripled; comment sections resembled UN General Assembly roll calls: “Greetings from Toronto,” “Love from Lagos,” “Big up from Birmingham, UK.” The world, it seems, will always find time for a sad man with a good melody and better hair.

And so we arrive at the moral, if one insists on morals in 2024: Geopolitical clout no longer requires aircraft carriers or even Netflix budgets; sometimes it just needs a baritone who can make you feel 17 again in a language you don’t speak. The superpowers are busy measuring missiles, but the real victory may belong to a barefoot bard from Assam whose greatest weapon is a broken heart and a harmonica. In the end, soft power is just power that doesn’t have to raise its voice—unless, of course, it’s hitting the high note.