Nathaniel Rateliff: Exporting American Heartbreak to a World Already on Fire

Nathaniel Rateliff: The Whiskey-Soaked Minstrel Exporting Heartbreak to a Planet Already on the Brink

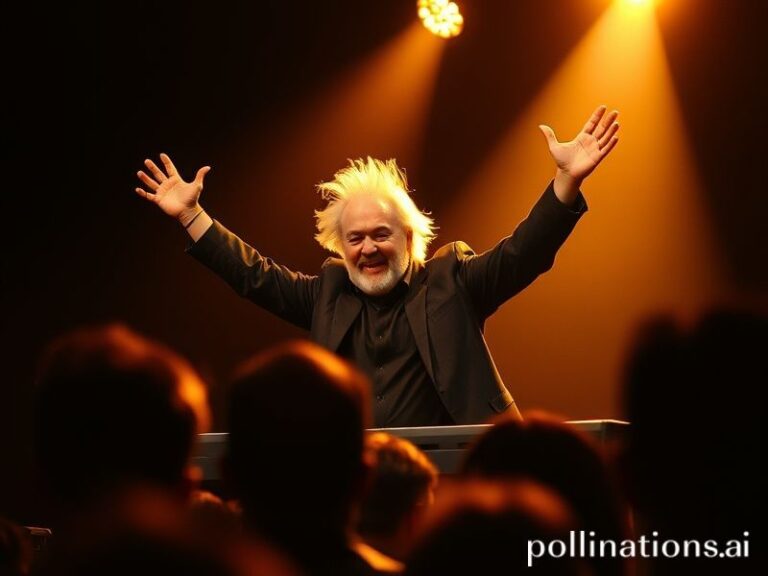

By the time the sun rises over the Mekong, Nathaniel Rateliff has already soundtracked three break-ups, two political implosions, and one very confused rooster in a Vientiane hostel courtyard. In a world where Spotify algorithms decide geopolitical mood swings faster than the UN Security Council can agree on lunch, the bearded troubadour from Hermann, Missouri has become an unlikely—but entirely logical—global export. After all, when glaciers calve and supply chains snap, what’s more universally marketable than a man howling about loneliness while wearing a trucker hat?

Rateliff’s ascent from Denver dive bars to international festival headliner is less a fairytale than a case study in late-capitalist emotional arbitrage. His 2015 single “S.O.B.”—a hand-clapping, foot-stomping hymn to functional alcoholism—now ricochets across six continents like a drunk text from an ex you thought had died. Berliners chant the chorus while queuing for €15 club sodas; salarymen in Osaka mumble the verses into last trains; even the Taliban, it is rumored, have a WhatsApp sticker pack of Rateliff’s anguished grimace. When the apocalypse comes, archaeologists will unearth a cracked jukebox in some irradiated cantina still spinning “You Worry Me” and conclude that humanity’s final collective act was to dance-weep in 4/4 time.

The economics are almost poetic. Each international ticket sold offsets roughly 0.0003% of the carbon emitted by the private jets conveying him between stages, a ratio the IMF politely calls “sustainable branding.” Meanwhile, the man himself—equal parts gospel shouter and reluctant influencer—keeps a straight face while promoters in Dubai hand him non-alcoholic beer and whisper, “The sheikh loves your pain.” In a region where public sobbing is usually reserved for onion shortages, Rateliff’s raw-throated confessions have become the soundtrack to gilded ennui. Somewhere in Riyadh, a princeling’s Tesla cruises the corniche at 2 a.m., subwoofers rattling “And It’s Still Alright,” because nothing says existential dread like chrome-plated luxury.

Europe, naturally, treats him as anthropological proof that America still produces something besides conspiracy theories. French critics compare his gravelly timbre to Serge Gainsbourg gargling bourbon; Swedish musicologists publish peer-reviewed papers on how his horn section subliminally triggers hygge. The Brits, ever eager to colonize new despair, have rebranded him “Sheffield-adjacent soul,” which roughly translates to “we’ll claim anything if it charts.” Post-Brexit, Rateliff’s concerts now serve as de-facto summits where Remainers and Leavers alike drown their sorrows in overpriced lager, united only in the suspicion that the opening act was better.

Back home, the irony is thicker than the humidity at Bonnaroo. While the United States debates whether healthcare is a human right, Rateliff exports the precise brand of uninsured angst that foreign audiences find authentically “Americana.” His songs—miniature FEMA trailers of the heart—offer catharsis without the paperwork. Critics call it “emotional austerity,” which is a fancy way of saying the man turns trauma into merch and somehow makes you grateful for the transaction. When NPR asked about his global appeal, he muttered something about “common humanity,” then excused himself to vomit artisanal tequila behind a compost bin. Even his nausea is on-brand.

And so the caravan rolls on, powered by diesel, desperation, and the delusion that harmonized heartbreak might actually knit the world together. Tonight he’ll play to 10,000 Koreans who’ve never set foot in a dive bar but know every word to “Love Don’t.” Tomorrow it’s São Paulo, where inflation is 40% and the local currency is affectionately nicknamed “sad real.” Somewhere in the mosh pit, a kid in a knockoff Carhartt jacket will raise a plastic cup of Brahma, shout the chorus, and briefly believe that sorrow, like smartphones and soybean futures, is a global commodity best enjoyed communally.

Because if the planet’s going to burn, we might as well provide the soundtrack—and charge a two-drink minimum.