How One Spanish Philosophy Professor Allegedly Broke Global Finance (and Why We’re All Surprised It Took This Long)

**The Man Who Bought the World (and Other Tuesday Afternoons)**

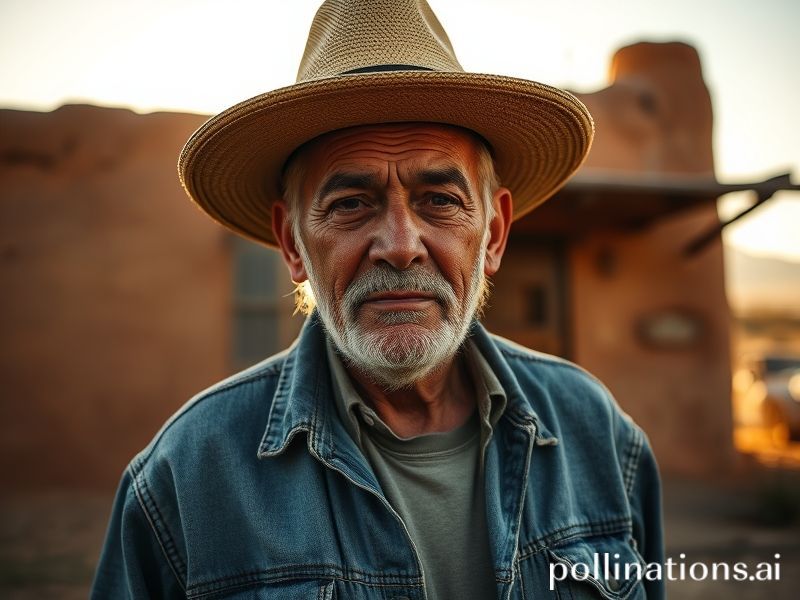

Ramón Juárez del Castillo, the man who allegedly single-handedly tanked three currencies, saved a fourth, and somehow managed to look bored while doing it, has become the international financial community’s favorite cautionary tale. The 47-year-old former philosophy professor turned cryptocurrency savant sits in a Madrid detention center, presumably contemplating the irony of becoming exactly what he claimed to despise: another middle-aged man who accidentally broke capitalism.

The global implications of Juárez del Castillo’s alleged three-week market manipulation spree read like a Gabriel García Márquez novel co-written by Gordon Gekko. Starting with what Spanish authorities dryly term “irregular trading patterns” in Barcelona’s cryptocurrency exchanges, his activities rippled outward with the elegant destructiveness of a champagne glass shattering in slow motion. By the time regulators in four countries noticed something amiss, Juárez del Castillo had reportedly moved approximately €2.3 billion through a maze of shell companies, digital wallets, and what investigators describe as “aggressively creative accounting.”

The beauty of this particular financial catastrophe lies in its democratic nature. When the Argentine peso plummeted 12% in six hours, Buenos Aires taxi drivers found themselves discussing blockchain technology between traffic lights. In Lagos, Nigeria, cryptocurrency traders watched their screens with the grim fascination of rubberneckers at a multi-car pileup. Even the usually unflappable Swiss had to admit their banking system experienced what one Zurich banker euphemistically called “heightened volatility”—Swiss for “we’re all going to lose our jobs and chalets.”

International regulators have responded with their characteristic speed and efficiency, by which we mean they’ve scheduled several important meetings for sometime next quarter. The Bank for International Settlements, that delightful anachronism headquartered in Basel, issued a strongly-worded statement that roughly translated to “we’re deeply concerned about things we don’t understand.” Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund dispatched a team of economists who will undoubtedly produce a 400-page report concluding that financial crimes are, indeed, bad.

The Juárez del Castillo affair has revealed the delightful paradox of our interconnected financial system: it’s simultaneously robust enough to facilitate instantaneous global transactions and fragile enough to be destabilized by one man with a laptop and what friends describe as “a somewhat flexible relationship with conventional morality.” The incident has prompted central banks worldwide to consider implementing what technocrats call “enhanced oversight mechanisms” and what everyone else calls “finally admitting we have no idea what’s happening.”

Perhaps most troubling is the philosophical dimension of this entirely preventable disaster. Juárez del Castillo’s academic writings, which his students reportedly found “either brilliant or completely incomprehensible,” suggested that traditional concepts of value and ownership were merely shared hallucinations. One can’t help but admire the commitment to proving one’s thesis through practical demonstration, though his alleged victims might prefer a more traditional approach involving footnotes and peer review.

As this sordid tale unfolds across international headlines, we’re reminded that the global financial system remains essentially a sophisticated confidence trick performed by people who wear very expensive suits. The difference now is that the confidence trick can be executed by anyone with sufficient technical knowledge and a moral compass that points firmly toward personal enrichment.

In the end, Ramón Juárez del Castillo may join that exclusive club of individuals who exposed the fundamental absurdity of our economic systems while simultaneously profiting from them. It’s a peculiar form of public service, reminding us that civilization remains three square meals and a stable Wi-Fi connection away from complete chaos. The real joke, of course, is that we’ll forget this lesson just in time for the next brilliant philosopher with a laptop and a dream.