Jacobo Morales: The Puerto Rican Prophet Who Saw Your Colonial Hangover Coming

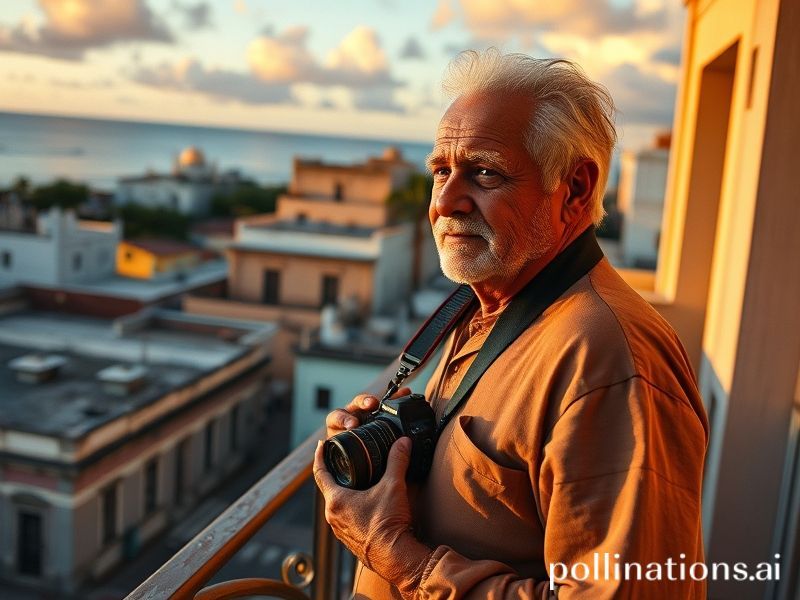

Jacobo Morales, the Puerto Rican filmmaker who has spent half a century reminding the world that small islands can still have big existential crises, turns 92 this year—an age at which most auteurs are content to let their Oscars gather dust while younger generations misquote them on TikTok. Yet Morales persists, a Caribbean Beckett in linen, still convinced that the human condition is best observed through the cracked lens of colonial irony and rum-soaked despair.

For the uninitiated (likely anyone under 30 who thinks “Puerto Rico” is a new crypto coin), Morales is what happens when Buñuel and Hitchcock have a love child raised on plantains and American tax shelters. His 1979 masterpiece “Dios los cría…”—roughly translated as “God Creates Them, Then Abandons Them to Federal Oversight Committees”—didn’t just put Puerto Rican cinema on the map; it spray-painted “We’re not your backyard” across the tourist brochures. The film’s vignettes of islanders navigating poverty with gallows humor became a Rosetta Stone for understanding how colonized peoples weaponize laughter against their occupiers—a skill now being studied by Ukrainians, Palestinians, and everyone else wondering if irony scales better than tanks.

The international significance here isn’t just that Morales exists—it’s that he refuses to stop existing. While Hollywood studios churn out algorithmic content designed to offend no one and bore everyone equally, Morales continues crafting films that suggest the human soul is best examined through the prism of bureaucratic absurdity. His 2004 film “Linda Sara” features a love story between a bankrupt businessman and a guerrilla fighter, because apparently even romance needs IMF restructuring in the 21st century.

What’s remarkable is how Morales’ particular brand of island fatalism has become weirdly prophetic. His recurring themes—identity crisis, economic dependency, the slow death of local culture under global capitalism—now read like a user’s manual for half the planet. When his characters debate whether to stay or flee their homeland, they’re essentially rehearsing conversations currently happening in Caracas, Lagos, and that trendy coffee shop in Brooklyn where everyone’s “totally moving to Lisbon next year.”

The global implications are deliciously ironic: a filmmaker from a territory that can’t vote for the US president has spent decades dissecting how American influence metastasizes worldwide. Morales’ work suggests that Puerto Rico isn’t America’s problem—it’s America’s crystal ball. The island’s status as neither state nor sovereign nation, forever in limbo, now feels less like an anomaly and more like a preview of coming attractions for everyone else caught between globalization’s promises and its wreckage.

Consider how his 1986 film “Nicolas y los demás” explored the brain drain decades before Silicon Valley started poaching talent from every village with WiFi. Or how his satire of tourist economies predicted the hollow victories of nations that traded their culture for cruise ship dollars. Even his occasional forays into magical realism—where bureaucrats literally turn into paperwork—seems less fanciful after watching Brexit negotiations.

As streaming platforms desperately mine “authentic” international voices to fill their content voids, Morales stands as a cautionary tale: authenticity ages like rum, not content. His films remain stubbornly un-binge-able, requiring the kind of attention span that TikTok has systematically destroyed. Yet they persist, like stubborn coral growing on a sinking ship, reminding us that some stories refuse to be reduced to data points in Netflix’s algorithm.

In the end, Jacobo Morales represents something increasingly rare: a regional artist whose regional concerns have proven universally relevant. His career suggests that the best way to speak to the world isn’t to chase global trends, but to dig so deeply into your particular patch of earth that you hit the molten core we all share. It’s a lesson that should terrify every content strategist who believes culture can be reverse-engineered for maximum engagement.