Sharia Law’s World Tour: From Aceh Canings to London Sukuk, the Planet’s Most Overhyped Legal System Checks In

Sharia Law: The Planet’s Most Misunderstood Legal System Tours the Globe

By Our Man in the Cheap Seats, Somewhere Between the Duty-Free and the Departure Gate

If jurisprudence were pop music, Sharia would be the aging rock star who still fills stadiums decades after the critics declared him washed-up. From the marble courthouses of Aceh to the parking-lot mosques of South London, the word “Sharia” manages to terrify, inspire, and bewilder—often within the same three-minute news segment.

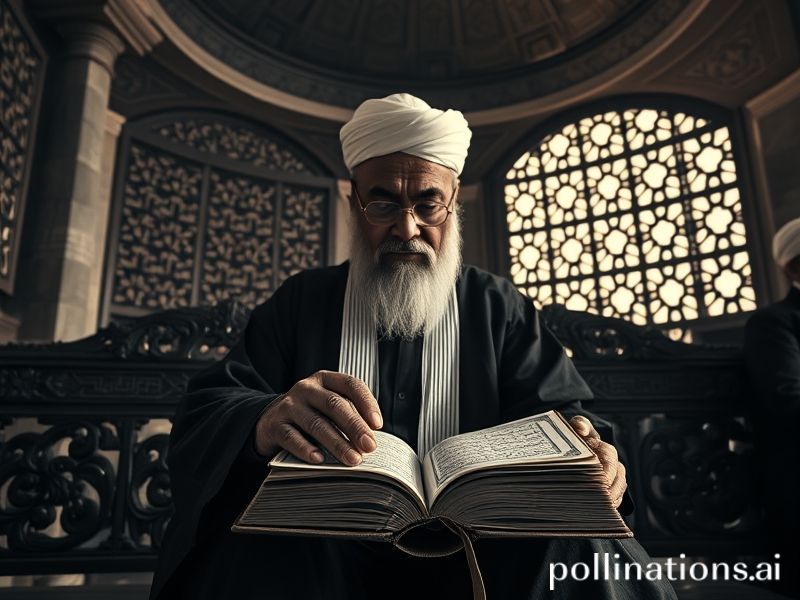

Let’s begin with the obvious: Sharia is not a single, laminated checklist handed down by a celestial bureaucrat. It is a sprawling jurisprudential tradition that spans 1,400 years, four major Sunni schools, two main Shia ones, and enough interpretive nuance to keep an army of bearded scholars in conference tickets for life. Think of it as the common law’s exotic cousin—same obsession with precedent, but with more Arabic calligraphy and fewer powdered wigs.

The West’s relationship with Sharia resembles a long-distance romance conducted entirely through voicemail. European tabloids greet every mention of “Islamic law” with the restrained hysteria of a Victorian maiden confronted by a rogue ankle. Meanwhile, American state legislatures race to ban something that, statistically speaking, has roughly the same chance of appearing in rural Arkansas as a snow leopard on a unicycle. The irony, of course, is that these preemptive strikes often come from the same parliaments that can’t agree on whether water is wet, let alone how to balance a budget without mortgaging the capital building.

Travel east, though, and the plot thickens faster than béchamel in a broken saucepan. In Indonesia—the world’s third-largest democracy—Sharia exists in polite détente with the national criminal code. Aceh’s public canings are livestreamed by journalists who, minutes later, file stories over 4G networks run by conglomerates whose boards meet in Jakarta karaoke bars. Malaysia’s syariah courts, meanwhile, quietly adjudicate family matters for 60 percent of the population while the federal constitution insists everyone play by secular rules—an arrangement about as stable as a Jenga tower during an earthquake drill.

Then there’s the Gulf, where Sharia wears a bespoke thobe and smells faintly of oud. Saudi Arabia’s guardianship system—recently trimmed, but not discarded—once required every woman to obtain male permission for everything short of breathing. Qatar and the UAE market themselves as Las Vegas with falcons, yet still cite Sharia when it’s convenient for debt collection or public-order offenses. Nothing says “heritage tourism” quite like a British footballer threatened with 100 lashes for a hotel-room scuffle, later commuted to a modest fine and an autographed jersey for the judge’s nephew.

Africa offers its own dark comedy special. Sudan, after three decades of Islamist rule, discovered that stoning adulterers is terrible for IMF credit ratings; the 2020 reforms reduced apostasy from a hanging offense to a strongly worded sermon. Nigeria’s northern states apply Sharia in patches, creating a jurisdictional patchwork where your right hand could be amputated for theft in Kano while your left remains blissfully intact in Lagos—an asymmetry even the most avant-garde fashion house hasn’t dared to market.

Europe, terrified of parallel societies, now runs “Sharia compliance” audits on mosques that can barely balance a zakat spreadsheet. France—never one to miss a theatrical moment—shut down a private “Sharia court” in the Paris suburbs that turned out to be little more than a retired imam dispensing marital advice between cigarettes. The tabloids screamed “Mini-Islamic State on the Seine,” proving that nothing sells print like the prospect of halal baguettes.

Global finance, ever allergic to theology, suddenly discovered “Sharia-compliant bonds” (sukuk) after 2008, when bankers realized that prohibiting interest also prohibits certain species of fraud. London now prides itself on hosting the largest Islamic finance market outside the Muslim world, a city where champagne bars offer alcohol-free bubbly for the pious fund manager who still wants to toast the quarterly hemorrhage of other people’s money.

So what does Sharia actually mean in 2024? For the affluent, it’s a branding exercise—an Islamic fintech app that rounds up your coffee purchase and donates the micro-change to charity. For the poor, it remains the only court that will hear a land dispute faster than the grave. For autocrats, it’s a handy speed bump on the road to democracy; for dissidents, a rhetorical cudgel to beat those same autocrats about the head. Everyone claims God is on their side, but the Almighty appears to be hedging His bets, probably consulting lawyers before issuing any further revelation.

The broader significance, then, is not whether Sharia is “good” or “bad”—human beings have already demonstrated infinite ingenuity in making any legal system oppressive or benevolent. The real takeaway is that globalization has turned sacred law into yet another export commodity, shipped, shrink-wrapped, and focus-grouped like Korean skincare. In a world where moral certainty is auctioned by the tweet, Sharia’s world tour reminds us that every society gets the theocracy it can afford, and the invoice is usually payable in blood, oil, or Wi-Fi passwords.

Until the species evolves beyond its need for rules carved in stone (or uploaded to the cloud), expect the argument to drag on—louder, longer, and with ever more creative footnotes. In the meantime, keep your passport current, your cynicism charged, and remember: whether you’re flogged, fined, or merely unfriended, someone, somewhere, is billing by the hour to decide what God meant. And He, She, or They are definitely not picking up the tab.