Canada’s Soft-Power Siren: How Sarah McLachlan Weaponized Wistful Melancholy Across the Globe

Sarah McLachlan and the Global Export of Wistful Melancholy

————————————————————-

Somewhere between a UN peacekeeping convoy and a container ship of tear-stained Kleenex, the British Columbian soprano has become Canada’s most reliable soft-power weapon. Sarah McLachlan’s voice—equal parts lullaby and guilt trip—now drifts through taxicabs from Lagos to Lahore, duty-free lounges in Dubai, and boutique hotel lobbies in Buenos Aires that still think “adult contemporary” is a compliment. If Céline Dion is Canada’s cruise-missile balladry and Drake its awkward cultural attaché, McLachlan is the stealth drone: quiet, circling, impossible to shoot down without looking like a monster.

Her international breakthrough, of course, arrived gift-wrapped in abandoned puppies. The 2007 ASPCA television spot—two minutes of trembling beagles scored to “Angel”—proved that American guilt could be weaponized for cross-border fund-raising. Europeans, who pride themselves on ironic distance, folded faster than a German coalition government. Within months, shelters from Seville to Sofia reported a 30 % spike in donations, all accompanied by e-mails in comic-sans begging forgiveness for mankind’s original sin of inventing the cardboard box. McLachlan later admitted she can’t watch the ad without tearing up; the rest of us can’t watch it without frantically lunging for the remote like it’s a live grenade.

But the singer’s geopolitical utility didn’t stop at abused Labradors. After the 2010 Haiti earthquake, her single “World on Fire” was piped into IDP camps by well-meaning NGOs who apparently confused trauma therapy with a Lilith Fair encore. Haitian radio hosts gamely translated the chorus, though one Creole rendering—“the world is on fire, and we just keep on selling toothpaste”—sounded less inspirational than prophetic. Meanwhile, in Japanese karaoke bars, “Building a Mystery” became the ironic go-to for salarymen who’d rather sing about gothic heartbreak than discuss quarterly sales targets. Nothing screams late-stage capitalism like a Tokyo exec belting lines about a “beautiful fucked-up man” while clutching a Suntory highball.

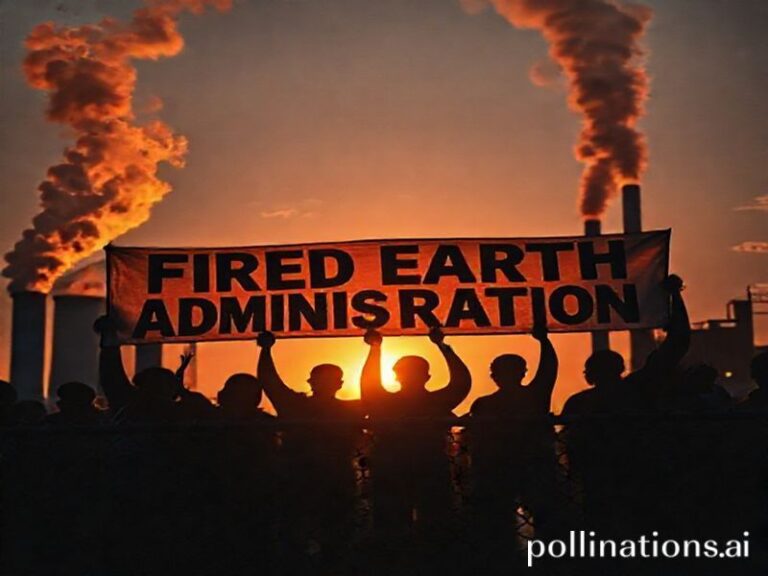

UN agencies have caught on. UNICEF now uses McLachlan’s 1993 hit “Possession” in training modules about consent, presumably on the theory that nothing clarifies bodily autonomy like a song originally inspired by stalker fan letters. Over in Geneva, interns joke that if you play “I Will Remember You” backward, you can hear the budget for the Paris Climate Accord dissolving. Dark humor, yes, but so is climate diplomacy.

Critics grumble that McLachlan’s brand of earnest sorrow is the musical equivalent of a white-savior Instagram filter. Yet even they concede the numbers: 40 million albums sold worldwide, a touring footprint that rivals the Cirque du Soleil’s carbon guilt, and Spotify streams that outpace entire Scandinavian countries. Her Lilith Fair alumni network—once dismissed as a benign estrogen cartel—has quietly seeded women’s music festivals on every continent except Antarctica, which is still holding out for Adele.

What keeps the machine humming is the universality of exquisite sadness. In South Korea, “Angel” scores the nightly news montage of politicians apologizing for corruption scandals. In Mexico City, “Adia” serenades gridlocked commuters who’d rather contemplate divorce statistics than the air-quality index. Even the Taliban—no fans of Western pop—once used an instrumental loop of “Hold On” in a propaganda video about perseverance, proving that irony, like opium, is a borderless commodity.

And so the gentle Canadian continues her quiet conquest, armed only with a piano, an acoustic guitar, and the unshakable conviction that every human heart contains at least one hairline crack she can widen into a canyon. In an age of drone strikes and disinformation, McLachlan’s strategy is disarmingly simple: make them cry, then pass the hat. It’s not regime change, exactly, but it pays for a lot of kibble.

As the planet slides from crisis to crisis, her voice lingers like the last civilized guest at a party that started on fire. Somewhere a Labrador retriever lifts its head, hears that familiar minor key, and thinks—against all evolutionary odds—maybe someone, somewhere, still gives a damn. That, in the current global inventory of hope, is no small export.