Elvis Presley’s Global Passport: How a Dead Rock Star Outmaneuvers Border Control and Defines Soft Power

Elvis Has Left the Building—But His Visa Is Still Valid Everywhere

By our man in the departure lounge, still waiting for the connecting flight to immortality

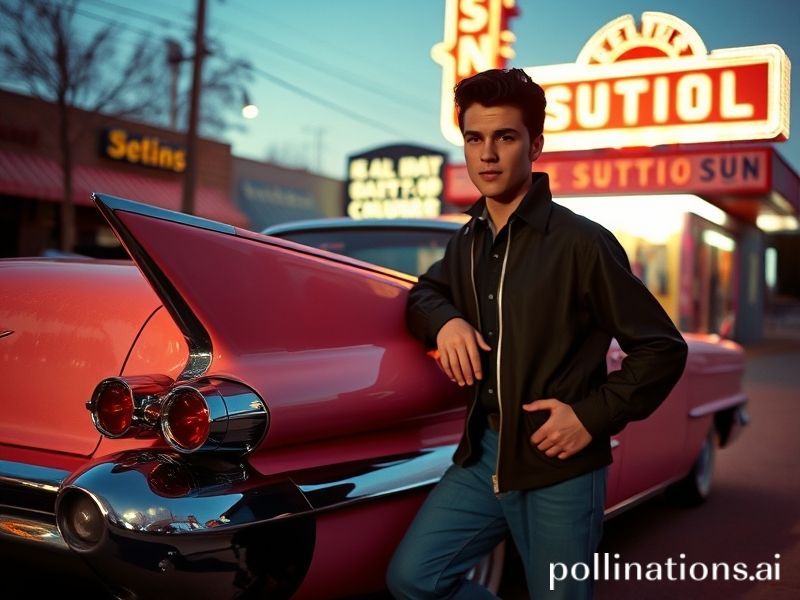

MEMPHIS, CAIRO, SÃO PAULO—Somewhere between the 1956 quarantine of “Heartbreak Hotel” on the BBC and last week’s Elvis-themed wedding in Manila, the corpse of Elvis Aaron Presley acquired a passport with unlimited pages. Six decades after his ostensible death, the King circulates more freely than most living humans: no visa queues, no PCR tests, no awkward explanations to customs about why you’re carrying a sequined jump suit and a fried-peanut-butter-and-banana sandwich. Globalization’s dirty secret is that we ban laborers, tomatoes, and even memes at the border, yet we wave through a dead Mississippian who impersonated Black music for suburban teenagers.

Consider the geopolitical itinerary. In Israel, ultra-Orthodox rabbis once denounced him as “the shaking abomination”; today, Tel Aviv bar mitzvahs hire Elvis impersonators named Guy and Uri. In Japan, where the post-war constitution was ghost-written by Americans who also exported jukeboxes, Elvis is a national ancestor: Tokyo’s high-speed rail system pipes “Blue Suede Shoes” into the restroom stalls, because nothing says hygiene like rockabilly. Meanwhile, in the crown prince’s neon Riyadh, Elvis tribute nights operate under the slogan “1973 Vegas, minus the alcohol”—a phrase so oxymoronic it could be the Saudi Vision 2030 mission statement.

The developing world has repurposed him with admirable pragmatism. In the Philippines, impersonators double as wedding singers and karaoke repairmen; if the machine eats your disc, Elvis can fix it with a screwdriver between verses. Cuban state television broadcasts “Jailhouse Rock” every July 26—apparently unaware the plot celebrates breaking out of prison, a metaphor too on-the-nose for a country where Wi-Fi is rationed like bread. And in Prague, a generation that overthrew communism by chanting Havel now weekends at “Elvis Presley’s Bar,” where a bust of the King wears a plastic Guevara beret—two revolutionary icons for the price of one hangover.

Economists call it soft power; the rest of us call it involuntary karaoke. The Elvis Industry—estimated at $500 million annually—out-earns the GDP of several Pacific micro-nations whose main export is passports to money launderers. Graceland welcomes more pilgrims per year than Lourdes, though only one of those destinations guarantees you a $38 guitar-shaped air freshener. UNESCO, ever the conscientious arbiter of human heritage, still refuses to inscribe “Hound Dog” as intangible cultural property, perhaps fearing North Korea will demand equal time for “Pyongyang Boogie-Woogie.”

All of which raises the eternal question: did Elvis really die on that bathroom floor in ’77, or did he simply defect to a planet where every passport bears his face? The evidence leans toward the latter. Consider: no corpse photo, a wax-sealed crypt, and a touring schedule that—thanks to hologram technology—now outpaces when he was alive. Even the coronavirus couldn’t cancel him; Italy’s first post-lockdown concert was a socially distanced Elvis revue in Turin, where fans in surgical masks swayed like a field of blue, sequined corn. If death is the final border, Elvis has become the world’s first undocumented immortal, working nights in every time zone.

The joke, of course, is on us. While nations weaponize trade routes and vaccine patents, we have collectively agreed to let a hillbilly in eye shadow arbitrate our sentimental education. Somewhere in Mosul, a teenager who has never met an American hums “Can’t Help Falling in Love” while rebuilding his school; in Bogotá, a former FARC child soldier croons “Love Me Tender” during demobilization therapy. The planet burns, democracies stall, supply chains snap—and still the King’s voice loops through duty-free speakers like an airdropped tranquilizer.

So when the last glacier calves into the ocean and the final customs officer turns off the light, don’t be surprised if the closing announcement is delivered in a familiar drawl: “Thank you very, ladies and gentlemen. The planet has left the building.” And somewhere, in a language you don’t speak, the crowd will demand an encore, because that, dear reader, is how the world ends—not with a bang, but with a hip swivel.