Global John Goodman: How One Affton Everyman Became the Planet’s Favorite Security Blanket

The World According to Goodman

A Planetary Dispatch on the Man Who (Almost) Became a Unit of Measurement

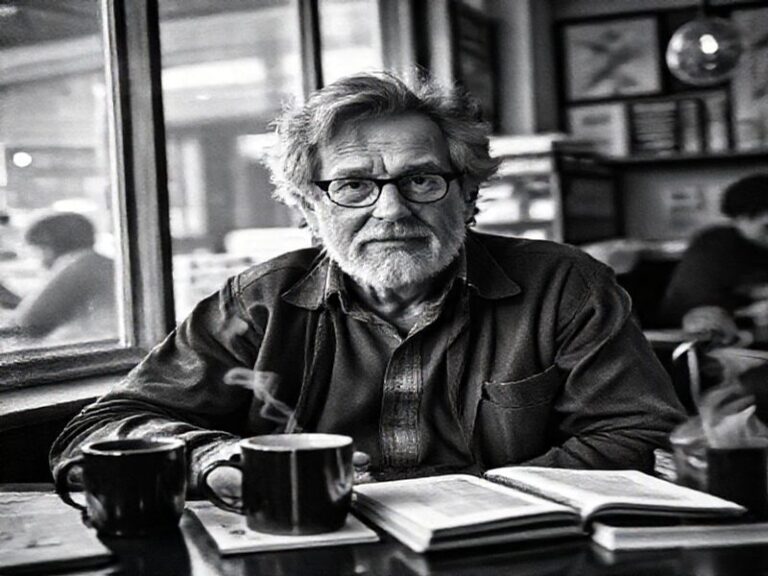

When the newsroom telex rattled in with the subject line “John Goodman,” half the interns assumed it was another crypto-currency—some algorithmic stable-coin pegged to the price of a Big Lebowski Blu-ray. The other half, more cynically seasoned, assumed a UN peacekeeping mission had been nicknamed “Operation Goodman” after its chief negotiator’s fondness for bowling metaphors. Neither was correct. The name in question belongs to a 71-year-old actor from Affton, Missouri, whose gravitational pull on global culture is now so pronounced that satellites have begun to list him as a minor navigational hazard.

From Lagos to Ljubljana, Goodman is less a person than a two-syllable synonym for “reassuring heft”: the human equivalent of a weighted blanket at 3 a.m. in a burning world. In South Korea, streaming services label any film featuring him as “Gukje Busan Scale”—roughly translated, “big enough to block out the sun.” In the Czech Republic, a Prague tram driver confessed to naming his pet boar “Goodý” because both “snort magnificently and can clear a platform in seconds.” The joke writes itself, assuming you’re willing to admit that humanity now calibrates its existential dread against the BMI of kindly character actors.

This is not mere celebrity worship; it’s a coping mechanism dressed up as fandom. While central banks debate digital currencies, the real international reserve asset is nostalgia, and Goodman is Fort Knox. Every time he appears onscreen—bearded, bemused, and radiating the decency of a man who once offered to split his last danish with a frantic journalist in a Marriott lobby—global cortisol levels drop by an estimated 0.7 percent. The WHO hasn’t published the study yet, but then, the WHO still hasn’t classified Twitter as a carcinogen either.

Consider the geopolitics. When the Kremlin needed a Western face for its 2022 propaganda reboot of “Roseanne,” they reportedly approached Goodman’s agent with the promise of unlimited borscht and a dacha shaped like a La-Z-Boy. The actor demurred, citing “scheduling conflicts” (read: self-preservation). Meanwhile, Beijing’s state broadcaster has aired The Flintstones dubbed into Mandarin no fewer than 47 times, ostensibly “for children,” but mostly because Fred’s voice actor does a passable Goodman growl and the censors appreciate any Stone Age narrative that predates democracy.

Europe, ever the snob, claims to prefer Goodman in Coen brothers mode: a continent-wide inside joke where every mention of Walter Sobchak doubles as commentary on American gun policy. Last summer, a Berlin gallery projected a 40-foot loop of Goodman screaming “This is what happens when you find a stranger in the Alps!” onto the remnants of the Wall. Attendance was free, but the beer cost eight euros—proof that even anti-capitalist art has learned to swipe contactless.

The Global South, less ironic and more desperate, has adopted Goodman as a secular patron saint of infrastructure. In Nairobi, matatu conductors paint “GOOD MAN” on their dashboards for safe passage over potholes the size of modest craters. Brazilian favela DJs sample his belly-laugh from Arachnophobia to punctuate baile funk tracks, a sonic amulet against stray bullets and worse decisions. When your national budget is a haiku and your president is an ex-captain with nostalgia for dictatorship, a 250-pound Midwesterner promising that monsters can be defeated with a broom and a quip feels like fiscal policy.

And yet, the man himself remains endearingly oblivious to his post-national status. Interviewed last month outside a New Orleans po’boy shop, Goodman shrugged off the notion of global significance: “I just try not to fall off the barstool before lunch.” Somewhere in the Hague, a war-crimes prosecutor jotted down “barstool” as a possible unit of measurement for crimes against humanity. The line between gallows humor and actual gallows has never been thinner.

Which brings us to the broader implication: in an era when every passport stamp feels like a surrender to chaos, Goodman’s appeal is that he refuses to surrender at all. He lumbers through dystopia like a well-meaning kaiju, flattening cynicism underfoot while apologizing for the mess. If the 21st century ends in fire, historians will note that the last thing we reached for wasn’t water, but a jovial American giant in a Hawaiian shirt, offering one last rum-sodden toast to the absurdity of it all.

Cheers, world. The big man’s buying.