Green Mermaid Retreat: How Starbucks Closures Signal Globalization’s Bitter End

**The Great Caffeine Retreat: Starbucks Closures Signal the End of an Empire Built on Misspelled Names and Middle-Class Aspirations**

The green mermaid is swimming away from her empire. Starbucks announced another wave of store closures across North America this week, adding to the 400 locations already shuttered since 2020. While corporate spokespeople blame “changing consumer behavior” and “foot traffic patterns,” the international implications paint a darker portrait of our caffeinated civilization’s decline.

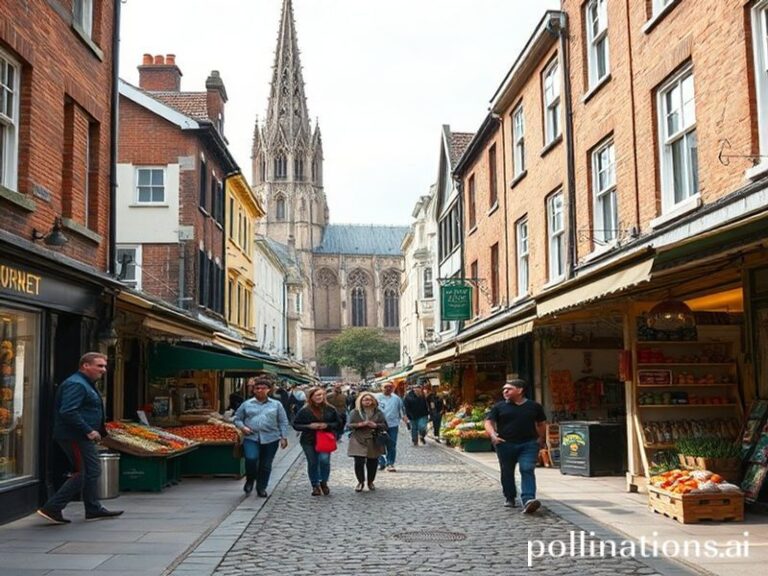

From Shanghai to São Paulo, the familiar green awning has become as ubiquitous as McDonald’s golden arches, serving as a reliable indicator that your neighborhood has officially gentrified beyond recognition. But as these temples of laptop-tapping creatives and remote workers begin to vanish, we’re witnessing something more profound than a simple corporate restructuring—we’re watching the slow-motion collapse of the Third Place, that mythical realm between home and work where human connection supposedly flourishes over $7 lattes.

The timing feels almost poetic. Just as we’ve trained an entire generation to believe that productivity requires constant caffeine infusion and WiFi passwords, the very infrastructure enabling our collective addiction is crumbling. Perhaps the universe has developed a sense of irony after all.

In Europe, where actual cafés with character and reasonable prices have existed for centuries, Starbucks’ retreat barely registers. Parisians shrug with Gallic indifference, while Italians—who regard American coffee culture with the same horror Americans reserve for British dental care—can barely suppress their satisfaction at watching the Seattle invader beat a strategic retreat. Rome’s single Starbucks location, opened in 2018 after years of cultural resistance, now stands as a monument to American hubris, like a McDonald’s next to the Pyramids.

The Asian market tells a different story. In China, where Starbucks planned to open a new location every 15 hours at its peak, the closures represent a stunning reversal of fortune. The company’s ambitious expansion—600 stores annually across the Middle Kingdom—has collided with local competitors like Luckin Coffee, who somehow convinced consumers that coffee should cost less than a small mortgage payment. The irony is delicious: American capitalism defeated by Chinese efficiency in the race to overcharge for burnt beans.

Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, Brexit’s economic hangover has made that morning flat white an unaffordable luxury. British consumers, faced with choosing between heating their homes or maintaining their caffeine habits, are rediscovering the revolutionary concept of making tea at home. The nation that once colonized half the world for spices is now learning that Nescafé isn’t actually that bad when the alternative is bankruptcy.

The broader significance extends beyond mere corporate strategy. Starbucks represented something more than coffee—it was the physical manifestation of globalization’s promise, a place where a businessman from Mumbai could order the exact same overpriced beverage as a student in Mexico City. Its decline signals not just changing consumer preferences but the fracturing of our shared global consumer culture.

As remote work becomes permanent and downtown cores hollow out across the developed world, we’re witnessing the death of the coffee shop as de facto office. The laptop warriors who once colonized corner tables for eight-hour “meetings” are now scattered to their kitchen tables, leaving baristas to wonder why they ever learned to draw leaves in foam.

The green mermaid’s retreat leaves behind more than empty storefronts. It leaves us with questions about what happens when the places that held our communities together—however artificially—disappear. When the last Starbucks closes, will we finally admit that we were never really paying for coffee, but for the illusion of belonging in an increasingly isolated world?

Perhaps we should have seen this coming. Any business model built on selling $2 of ingredients for $8 while convincing customers they’re purchasing “an experience” was always skating on thin foam.