Global Grief Translator: How the Newsreader Became the World’s Last Shared Campfire

The Newsreader: Global Mouthpiece, Local Punching Bag, Universal Mirror

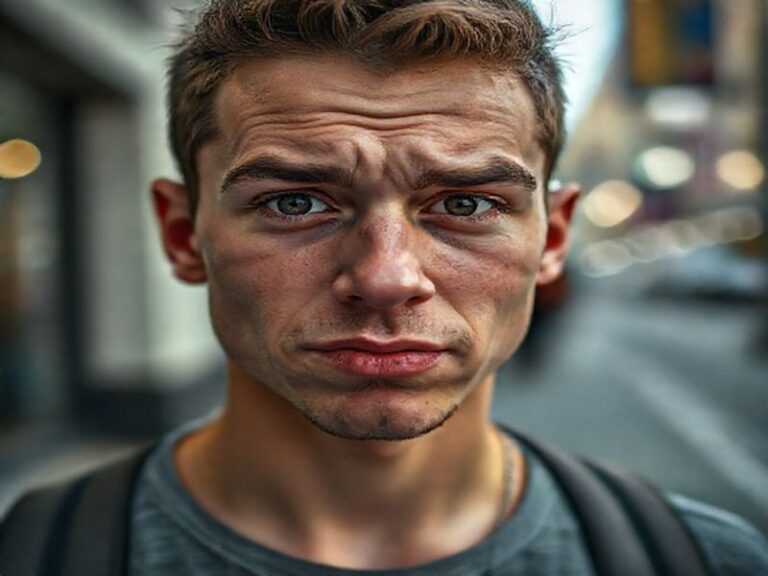

If you listen closely at 3 a.m. in any capital city, you can almost hear the same voice repeating itself in 24 languages: “Good evening, wherever the hell you are.” The newsreader—once a stately uncle in horn-rimmed spectacles, now a caffeinated hologram with perfect hair—has become the world’s most travelled citizen without ever leaving the studio. From Lagos to Lisbon, the script changes, the accent mutates, but the ritual remains: someone impeccably lit tells the rest of us what fresh calamity we missed while we were microwaving leftovers.

Take the 8 p.m. slot in Tokyo. NHK’s Yuko Shimada bows fractionally, as though apologising in advance for the typhoon, the yen, and the Prime Minister’s latest “regrettable misunderstanding.” Ninety minutes later, the same footage of swirling clouds appears on Globo in Rio, where the anchor’s teeth are impossibly white against a set the colour of a carnival gone septic. By the time BBC World loops it, the storm has been upgraded to “historic,” the yen to “volatile,” and the Prime Minister to “embattled,” which is British for “we’re bored but still judging.” Same planet, same pixels, different filter.

The international significance is obvious: the newsreader is the last shared campfire before we all retreat to algorithmic caves. That’s why autocrats, tech bros, and hedge-fund messiahs spend fortunes either co-opting or cancelling them. When Russia’s Channel One had its on-air protest moment—Marina Ovsyannikova waving an anti-war sign—Kremlin spinmeisters understood the stakes: if the script slips even once, the illusion of consensus shatters. Meanwhile, in Silicon Valley, a streaming start-up is beta-testing AI anchors whose facial expressions are calibrated by sentiment analysis scraped from Twitter at 4:12 p.m. GMT. The goal is to deliver “empathy at scale,” which is either touching marketing copy or a confession that humanity has been downgraded to a plug-in.

Yet the newsreader endures precisely because they are still human enough to fail. Remember the Lebanese anchor who cracked up mid-bulletin when the teleprompter fed him his own obituary? (A software glitch, or a grim prank by the understudy—never clarified.) For 37 seconds he stared into the abyss, and half of Beirut stared with him. The clip went viral, soundtracked by a Finnish DJ, subtitled in Tagalog, and turned into NFTs by a teenager in Lagos. Somewhere in that ridiculous relay, an actual connection sparked: we are all, briefly, the same bewildered mammal.

Of course, the darker joke is that while the faces change, the sponsors don’t. A pharmaceutical giant funds the health segment warning about side effects of drugs manufactured by… the same pharmaceutical giant. A petro-state underwrites the climate summit coverage, ensuring the word “transition” is always preceded by “gradual.” Viewers in Jakarta notice the same Chevron logo lurking behind CNN and France 24; they laugh, because the alternative is screaming. The newsreader must deliver this cognitive dissonance with a straight face, a skill taught in journalism schools under the formal name “credibility management” and informally as “keeping your soul on retainer.”

And so we arrive at the broader significance: the newsreader is the globe’s emotional shock absorber. When Kabul fell, the Afghan anchor wept on air; Australians watching breakfast television felt a pang, then buttered toast. When Queen Elizabeth II died, the BBC’s black tie travelled faster than the official announcement, and within minutes Zambian radio hosts were lowering their voices to hushed Anglican baritones. We outsource our grief, our outrage, our cautious optimism to a rotating cast of well-lit strangers, because processing planetary-scale tragedy in real time is above our pay grade.

Will the future still need a human to say “good night” after enumerating the day’s catastrophes? Probably. Even the most persuasive deepfake can’t replicate the involuntary tremor in a voice when the death toll jumps from “dozens” to “hundreds.” That micro-fracture in composure is the last authentic passport stamp in a borderless media empire. Until androids learn to sweat under the lights, the newsreader remains what they’ve always been: the world’s simultaneous translator and designated scapegoat, paid to look calm while the rest of us decide whether to riot or go to bed.

And tomorrow, somewhere, the same voice will clear its throat and begin again. “Good evening, wherever the hell you are.”