Shildon: The Tiny English Town That Explains Why the World Is Broken

Shildon, Co. Durham—population 9,565, two Greggs, one railway museum, and, depending on whom you ask, either the quiet epicentre of global decline or the last honest place left on Google Earth. To the casual commuter hurtling south on the A1(M), Shildon is a blink-and-you-miss-it blur of boarded-up terraces and weather-beaten “For Sale” signs stapled to lampposts. To the macro-economist, however, Shildon is the canary that stopped singing in 1984 and has been stubbornly refusing to breathe ever since—a petrified feather in the cap of post-industrial Britain and, by extension, the entire liberal-democratic order that once promised prosperity in exchange for a little light coal smoke.

Let’s zoom out. While venture capitalists in Palo Alto agonise over whether their NFT of a bored ape can be flipped for a Gulfstream G650, Shildon’s residents are crowdfunding a new roof for the community centre because the council’s austerity budget ran out somewhere between a Downing Street cheese board and a PPE contract signed in a pub car park. The juxtaposition is almost poetic: in the same week that El Salvador announced plans to build a tax-free Bitcoin city powered by a volcano, Shildon’s biggest energy debate centred on whether the chip shop could justify switching from beef dripping to sunflower oil without alienating the regulars. One nation’s future is another’s cholesterol.

The wider world, of course, pretends not to notice. Global indices treat Shildon as statistical dust—too small for the IMF’s spreadsheets, too stubborn for McKinsey’s slide decks. Yet the town’s muted despair is replicated from the Rust Belt of Ohio to the shoe factories of Wenzhou, from the mining towns of northern Spain to the car-plant dormitories outside Seoul. Shildon merely does decline with a particularly English politeness, like apologising while being mugged. If you listen closely, you can almost hear the shared planetary sigh of every place that used to make something solid and now survives on zero-hour contracts, payday loans, and the faint hope that Netflix won’t hike prices again.

Naturally, there are attempts at resurrection. A German discount supermarket has opened where the locomotive works once stood, its aisles of discount bratwurst a culinary Versailles treaty for the palate. The local council, fresh from a webinar on “placemaking,” has painted the pedestrian crossing in rainbow stripes so inclusive that even the town’s pigeons now strut with newfound pride. Meanwhile, a tech incubator in London—staffed by people who think Durham is a type of cheese—has floated the idea of Shildon becoming a “dark-sky tourism hub,” because nothing says cosmic wonder like standing in a former railway siding staring at Orion while your phone searches for a 3G signal.

And yet, perversely, Shildon endures. Its endurance is not the Instagram-ready resilience peddled by lifestyle influencers, but the grimmer, funnier kind: the pensioner who still waters plastic flowers in a disused planter “because someone has to,” the teenager live-streaming grime tracks from a bedroom wallpapered with fading Premier League posters, the bookmaker who accepts bets on how many days before the next ATM gets ripped out with a stolen JCB. These acts are miniature rebellions against the tyranny of economic inevitability. They are also, if we’re being honest, the only sane response to a world that keeps promising levelling up while secretly pressing the down button in the lift.

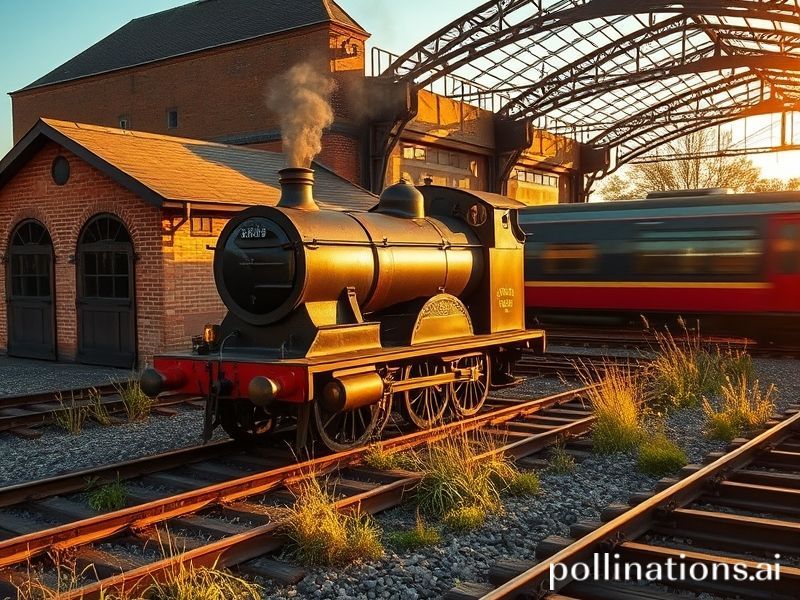

International significance? Shildon is the ghost at everyone’s banquet. It reminds Davos Man that the “Fourth Industrial Revolution” still needs somewhere to park its toxic waste, and that somewhere is always someone’s hometown. Shildon’s boarded windows reflect the global skyline of broken promises, from Shanghai’s empty apartment towers to Detroit’s derelict mansions. When the historians of late-stage capitalism finally get around to assigning blame, they could do worse than take a slow train—if one still runs—to Shildon station and inhale the scent of wet coal and abandoned dreams. It smells like the future, assuming the future still has nostrils.

Conclusion: Shildon will never trend on TikTok, headline a G7 communique, or mint its own meme coin. Instead it offers something rarer in our curated age: unvarnished evidence that the grand narrative of progress tends to skip certain pages. The town’s greatest export, then, is not nostalgia but perspective—delivered with a shrug, wrapped in drizzle, and priced at £2.80 return with a Railcard. Buy a ticket while you still can; the last train is always earlier than you think.