Global Supply Chains, Geopolitics & Gambling: Why Today’s Cubs Game Is Quietly Running the World

Cubs Game Today: A Pocket-Sized Apocalypse in Nine Innings

Chicago, Illinois – While the rest of the planet busies itself with lesser inconveniences—Ukraine’s blackouts, Gaza’s cease-fires that aren’t, and the Bank of Japan’s valiant attempt to make the yen feel wanted—ninety-seven countries are nevertheless watching a patch of grass on Lake Michigan where grown men in matching pajamas try to hit cowhide with a stick. The Cubs host St. Louis at 1:20 p.m. local time, which translates to 8:20 p.m. in Kyiv, 2:20 a.m. in Tokyo, and “who-cares-o’clock” in Ottawa, proving once again that the American pastime is the world’s most efficient time-zone irritant.

Global supply chains have bent themselves into balloon animals to deliver the game’s raw materials: Venezuelan leather, Taiwanese stitching, Costa Rican hardwood, and data packets routed through Dublin to avoid the EU’s privacy fines. A single pitch therefore contains more international cooperation than the last three UN Security Council meetings combined, even if the result is just another groundout to short.

Bookies from Macau to Malta have installed the Cubs as slight favorites, which in gambling parlance means “the universe is 52 % certain the Cubs will disappoint you.” The implied volatility on a Cardinals upset now trades higher than Turkish lira options, according to a London hedge fund that has apparently mistaken baseball for emerging-market debt. When asked why anyone would wager hard currency on a .500 team in May, the fund’s analyst replied, “Sir, we’ve priced in geopolitical risk; this is merely existential.”

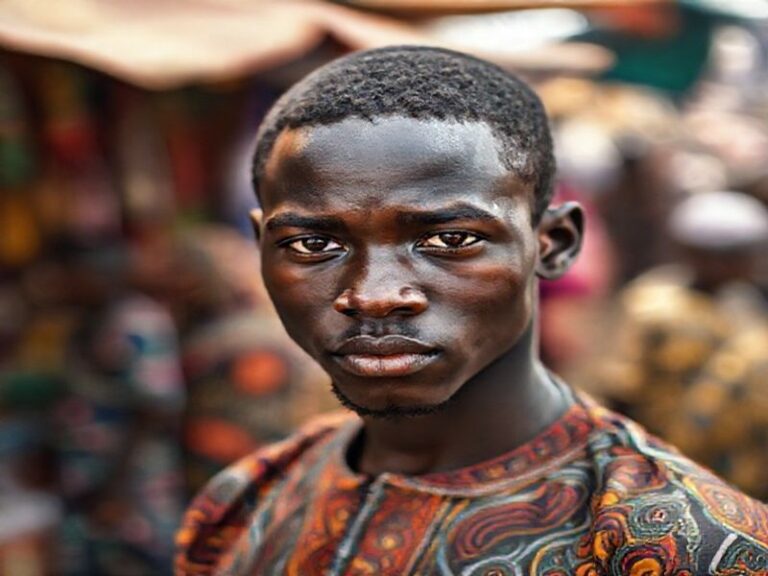

Across five continents, expatriate Cubs fans are streaming the game on sketchy websites that promise “HD quality” but deliver pixelated nostalgia. In Singapore, an oil-trading desk has turned the seventh-inning stretch into a drinking game keyed to every mention of “Wrigley weather.” In Lagos, a bar owner hangs a bedsheet for a screen and charges admission in naira; he claims the proceeds will “definitely not” fund a coup. Meanwhile, a retiree in Reykjavik stays up past midnight because he saw a 1984 highlight once and concluded the Cubs were “lovable,” a diagnosis the DSM-5 now lists as chronic optimism disorder.

The geopolitical subplot is not without its ironies. The Cardinals’ cleanup hitter swings a bat made from Canadian maple—NAFTA’s last functional limb—and the pitcher he faces throws a ball manufactured in China, where workers earn less per hour than the stadium charges for a domestic light beer. Somewhere a trade economist is updating a model to prove that even trade wars have mercy rules.

And yet, for two hours and fifty-three minutes, the planet’s attention will drift toward ivy-covered walls and a manual scoreboard that looks suspiciously like a pre-digital Bloomberg terminal. Climate refugees, crypto bankruptcies, and AI doomerism will all take a commercial break while a 23-year-old from the Dominican Republic tries to turn on a 96-mph fastball. If he succeeds, the crowd’s roar will be audible on seismographs in Ottawa; if he fails, Twitter will erupt with enough hot takes to melt what’s left of the polar ice caps. Either way, the International Space Station will glide overhead, indifferent, broadcasting the game to astronauts who have already seen the curvature of the Earth and still think Wrigley’s bleachers look small.

When the final out is recorded, the Cubs will either be a game above .500 or a game below it—a statistical shrug that nevertheless moves futures markets and at least one marriage in Brisbane. The planet will then return to its regularly scheduled catastrophes, slightly better rested for having spent the afternoon pretending that the most urgent question was whether a ball was fair or foul.

So yes, today’s Cubs game matters. Not in the way famines or elections matter, but in the way a haiku can matter: a tiny, perfectly useless construct that reminds us we’re all stuck on the same rock, circling the same sun, arguing about the same tag at second base. If that isn’t a metaphor for the twenty-first century, I don’t know what is—though I suspect the line for overpriced beer is shorter in Kandahar.