Birmingham’s Concrete Coliseum: How a Rebranded Box Became the World’s Fun-House Mirror

Utilita Arena Birmingham: A Concrete Coliseum for the Age of Disposable Fun

By Our Man in the Mid-Atlantic, nursing a lukewarm Balti and a colder world-view

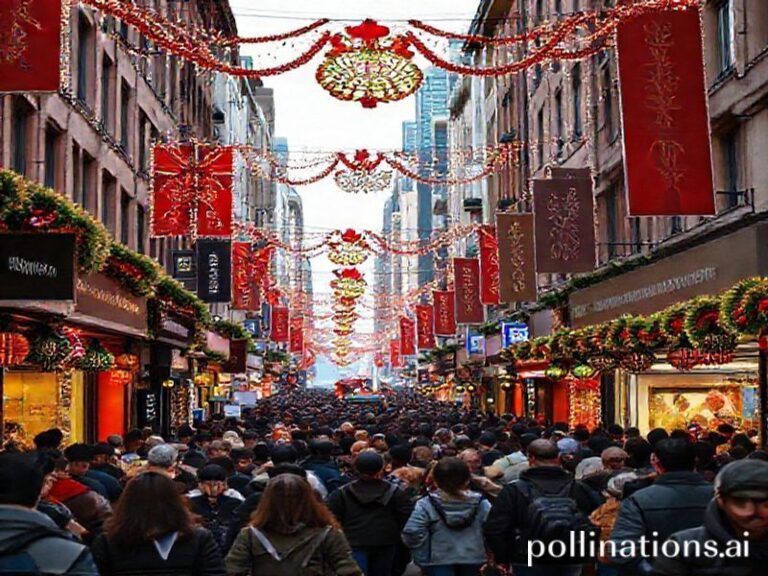

From the air, Birmingham’s utilitarian slab looks like a dropped shipping container that someone forgot to collect. Up close it is worse: a 15,800-seat Tupperware box squatting beside a canal network once used to move imperial loot and now mainly used by stag parties vomiting into the water. Welcome to Utilita Arena—formerly the Barclaycard Arena, formerly the NIA, formerly the “thing we still call the NEC by mistake.” In the grand tradition of British naming rights, each corporate landlord has sprinted away as soon as the energy market wobbled; Utilita itself is a utility firm whose logo glows a queasy green, as though the building is being slowly irradiated by its own electricity bill.

Yet, for all its aesthetic crimes against architecture, the arena is a surprisingly accurate barometer of global mood swings. When the Cold War thawed, Michael Jackson brought his Dangerous tour here in ’92, dangling a baby over the balcony of the Hyatt next door—a moment that now reads like an allegory for American exceptionalism: loud, sequinned, and ultimately litigious. During the 2012 Olympics, the arena hosted gymnasts who contorted themselves into shapes that would make a tax lawyer blush, proving that late capitalism can still monetise human elasticity. Today, it’s where K-pop juggernauts sell out in nine minutes flat, demonstrating that soft power now travels via serotonin-soaked choreography rather than gunboats.

The international implications are deliciously ironic. Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund has reportedly sniffed around a naming-rights deal, apparently keen to diversify from crucifixions into crowd surfing. Meanwhile, Chinese tech giants stream the concerts in 8K to teenagers in Wuhan who can lip-sync every Korean syllable yet still struggle with Birmingham’s accent in real life. Somewhere in a Pentagon sub-basement, an analyst is noting that the same bass frequencies capable of rupturing a teenage eardrum can also destabilise a dictator—provided the autocrat in question grew up on Eurovision.

Inside, the concessions tell their own geopolitical story. Pints of Carlsberg (Danish, brewed in Northampton) cost £7.50, a price point that could service a micro-loan in Laos. The nachos are topped with something legally obliged to call itself cheese, sourced from a supply chain so opaque it might as well be laundering conflict diamonds. And should your moral compass twinge, fret not: the arena offsets its carbon via a scheme involving trees planted somewhere so remote even Greta Thunberg’s sat-nav gives up.

The building’s very existence is a rebuke to British planning. It was thrown up in 1991, back when architects believed that if you stuck a few flags on concrete the public would feel patriotic instead of clinically depressed. Thirty-three years later, the flags have faded and the concrete has the complexion of an ageing smoker, but the arena endures—partly because demolishing it would cost more than another royal yacht, and partly because no city can now afford to lose 200 nights a year of captive consumers buying LED bunny ears at 400% markup.

Globally, the venue is a node in what urbanists call the “experience economy” and what cynics call the “pay-to-forget dystopia.” Every ticket scanned is another citizen opting for two hours of manufactured euphoria instead of asking why local libraries are closing faster than a Ryanair seat sale. Yet even here, resistance flickers. During a recent Billie Eilish gig, climate activists projected “Your future is being traded for merch” onto the façade. Security tackled them in 38 seconds—faster than the bar queues—proving that late-stage capitalism has reflexes like a cat on amphetamines.

As the lights dim and the first synth chord detonates, 15,800 phones rise in perfect synchrony, a constellation of blue rectangles filming a moment none of them will ever re-watch. Outside, the canal laps at rusting shopping trolleys like a lullaby for lost optimism. And somewhere beyond the ring road, the next naming-rights tenant waits in the wings, chequebook poised, ready to stamp its logo on our collective amnesia once again.