From Crude to Cloud: How John Mateer Turned Texas Oil Logic into Global Carbon Accounting Gold

PARIS — Somewhere between a smoky jazz bar in Montparnasse and a fluorescent-lit co-working space in Singapore sits John Mateer, a man whose surname translates to “morning” in Catalan yet whose career has unfolded almost exclusively under the dim glow of late-night deal-making. To the uninitiated, he is simply the latest American executive to pivot from Big Oil to Big Data, trading ExxonMobil’s Permian Basin for the cloud’s limitless ether. To the rest of us—those who measure passports in inches and cynicism in liters—Mateer is a walking allegory for our era: a polite Texan who helped pump carbon into the sky and now promises to vacuum it back out with the same spreadsheets.

The international press first noticed Mateer in 2019, when he left his post as Vice President of Digital at Exxon and popped up in Davos wearing a Patagonia vest that still smelled faintly of crude. He declared, without visible irony, that “data is the new hydrocarbon.” Delegates from Norway nodded approvingly—after all, they had just divested from hydrocarbons and purchased a carbon-capture start-up that runs on, well, data. The Chinese contingent took notes in triplicate. The Australians ordered another round of drinks and asked whether blockchain could somehow make coal sexy again. Mateer smiled the way only an oilman can: like someone who knows exactly how many angels fit on the head of a drill bit.

Fast-forward four years and Mateer is now CEO of VerdantIQ, a Houston-based firm that sells AI-powered emissions-tracking software to the very petrostates whose carbon he once helped liberate. The company’s client list reads like a UN roll-call minus the idealism: Saudi Aramco, Gazprom, Petrobras, and—because irony is renewable—BP. Verdant’s algorithms, we are told, can calculate the exact tonnage of CO₂ released when a Qatari sheikh lights his tenth birthday yacht on fire. The software then suggests offsets: planting mangroves in Indonesia, installing solar panels on Algerian orphanages, or simply buying “future not-yet-avoided” credits from a broker in Luxembourg who moonlights as a conceptual artist. It’s capitalism performing penance with the enthusiasm of a teenager buying condoms after the fact.

The global significance? Verdant just signed a memorandum of understanding with the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, meaning Mateer’s code will soon determine how much tariff Brussels slaps on Indian steel or Kenyan coffee. In other words, a man who once optimized fracking logistics in West Texas now gets to tax the air that surrounds your cappuccino. Trade ministers from Jakarta to Johannesburg are hiring consultants to decode the new math, while smallholder farmers wonder why their morning brew suddenly carries the geopolitical weight of a uranium shipment.

Meanwhile, China—never one to miss a profitable contradiction—has cloned Verdant’s platform, rebranded it “GreenTorch,” and is offering it at half price along with complimentary 5G towers. The race is on to see who can monetize guilt faster. Goldman Sachs has issued a 200-page report titled “Carbon Accounting as a Service: The Final Frontier,” helpfully noting that the total addressable market is “literally the atmosphere.” Analysts recommend going long on breathable air.

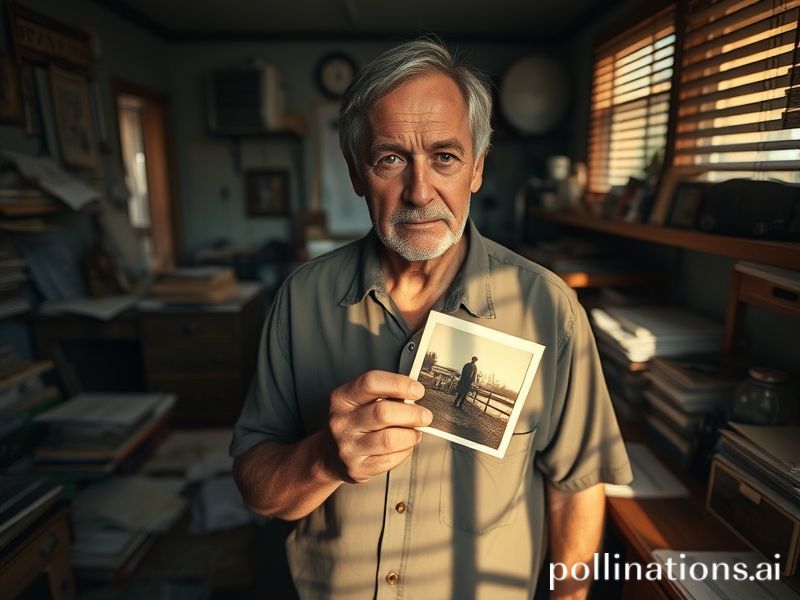

Back in Houston, Mateer tells investors he sleeps just fine, thanks to a weighted blanket stitched from recycled drilling permits. He keeps a framed photo on his desk: the 2005 Exxon board, all white teeth and offshore rigs, captioned “We Were Young Once Too.” When asked about legacy, he quotes Saint Augustine—whom he discovered via an AI-generated podcast—saying, “Give me chastity and continence, but not yet.” The quote is apocryphal, but so are half the offsets on his ledger.

So here we are, orbiting a planet where yesterday’s oilmen become today’s climate accountants, and the rest of us pay by the breath. John Mateer is neither hero nor villain; he is merely the middleman evolution coughed up when it realized extinction wasn’t great for quarterly earnings. Should we resent him or thank him? Probably both—then invoice him for the air conditioning.