How a 1930s Skull Fracture Went Global: Ace Bailey, the NHL’s First Viral Casualty

Ace Bailey and the Curious Global Afterlife of a 1930s Hockey Casualty

By “Scoop” Delacorte, Senior Correspondent, Dave’s Locker Foreign Desk

The first thing you notice, leafing through yellowing copies of the Toronto Star at the Hockey Hall of Fame’s basement archive, is how politely Canada once reported its on-ice manslaughters. “Bailey Sustains Severe Head Injury,” the headline demurred on 13 December 1933, as if Ace had merely spilled tea on his plus-fours. In truth, Ace Bailey—Toronto Maple Leafs star, Depression-era folk hero, and owner of a jawline so square it could balance a puck—was clubbed from behind by Boston’s Eddie Shore, cracked his skull on the ice, and nearly became the first NHL player to die for the entertainment of 12,000 paying customers who still expected change from a quarter.

Internationally speaking, the incident was a mere footnote in a decade already drunk on catastrophe: Hitler had just moved into the Reich Chancellery, Stalin was starving Ukraine for sport, and Japan was rehearsing its upcoming tour of Manchuria. Yet the Bailey affair managed to ripple outward in ways that would make a Davos panel blush.

First came the global optics. Radio bulletins carried the word “fatality” across the Atlantic within hours, prompting the London Times to muse—between adverts for liver salts and imperial soap—that North Americans had turned ice hockey into “gladiatorial ballet.” French sports daily L’Auto (fresh from inventing the Tour de France to sell newspapers and cigarettes) sniffed that if Canadians wished to beat one another senseless, they might at least adopt the more civilized schedule of a proper duel. Only the Soviet paper Pravda declined comment; they were busy rebranding famine as diet culture.

Then came the money. Bailey’s teammates hastily organized a benefit game on 14 February 1934—hockey’s first All-Star contest—raising CAD $20,000, a sum that could buy a small lake in Saskatchewan at the time. The gate receipts were wired to Bailey’s hospital room, where he was learning to walk again while contemplating mortality, compound interest, and the novelty of charity without a tax write-off. The NHL, sensing PR salvation, promptly institutionalized the All-Star Game, ensuring that every future generation of players could risk their ACLs for a mid-season exhibition nobody asked for.

What’s striking from the vantage of 2024 is how Bailey’s near-death foreshadowed the modern entertainment complex: a global audience monetizing human fragility in real time. Today the league’s concussion lawsuits crawl through U.S. courts like hungover sloths, while the KHL in Russia pays bonuses in undeclared crypto and the Swedes politely pretend their players never get hurt. Meanwhile, the IIHF sells broadcast rights from Abu Dhabi to Ulaanbaatar, each contract stipulating at least one slow-motion replay of a brain injury set to dubstep.

Bailey himself lived another 58 years, a longevity that irritated actuaries and delighted dark humorists alike. He watched the NHL expand southward—sunbelt franchises that treat ice like an exotic cocktail garnish—and saw Shore’s vicious hit rebroadcast in ever-slicker highlight reels, each iteration adding a Hans Zimmer drumbeat for emotional heft. By the 1980s, Japanese game shows were reenacting the collision with foam costumes; by the 2000s, a Swedish death-metal band sampled the crack of Bailey’s skull for a track titled “Stockholm Syndrome on Ice.”

In retirement Bailey became a rinkside philosopher, greeting tourists at Maple Leaf Gardens with the cheery prognosis that “sports build character—usually the brooding kind.” He died in 1992, just in time to miss the internet turning his tragedy into a meme template: “Gets skull fractured—still more coherent than your fantasy league takes.”

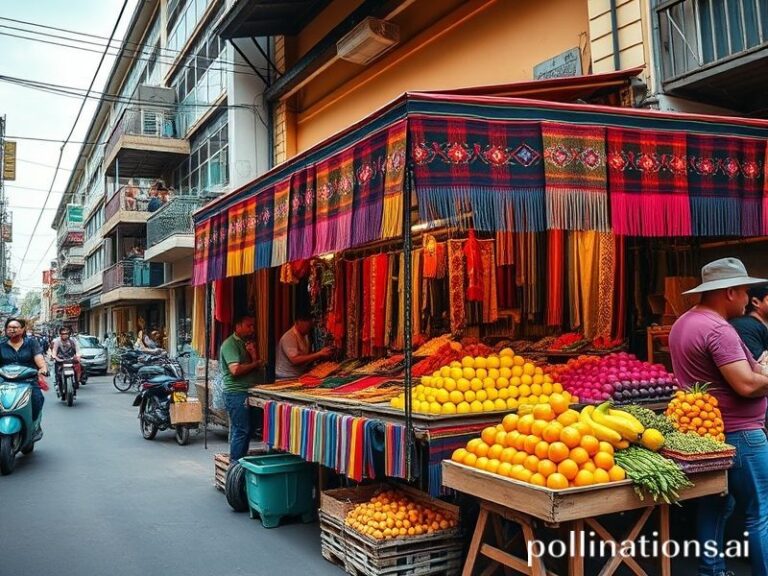

And so we arrive at the present, where Ace Bailey’s legacy is less a cautionary tale than a multinational case study in how efficiently capitalism converts trauma into content. From Toronto to Tbilisi, viewers now demand ever-higher speeds and ever-larger collisions, preferably sponsored by a sportsbook with a .tv domain registered in Curaçao. The more things change, the more they get streamed on delay in 47 languages, each with its own disclaimer about viewer discretion and mild brain damage.

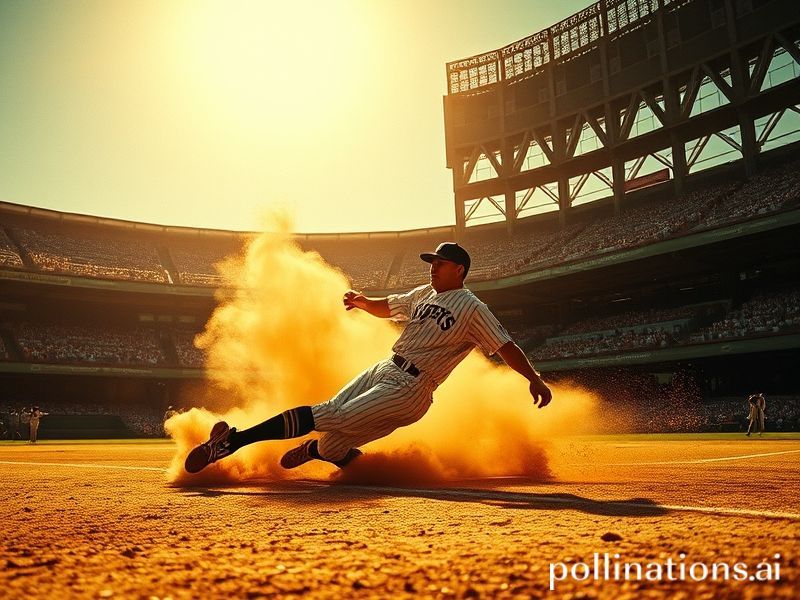

In the end, Ace Bailey didn’t just survive Eddie Shore’s stick; he survived the entire twentieth century’s experiment in turning pain into profit. The rest of us are still sliding, helmeted but unprotected, toward whatever fresh catastrophe the next broadcast rights package has in store.