Croatia: The Adriatic’s Over-Achieving Underdog Quietly Shaping Europe’s Future—One Hypercar at a Time

Croatia: The Mediterranean’s Prettiest Paradox Quietly Wagging the World

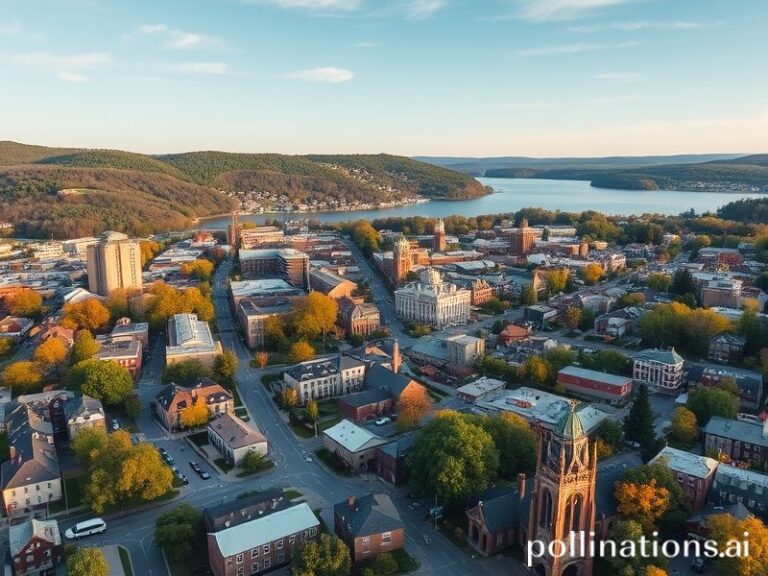

The first thing international investors notice about Croatia is that its coastline looks like Italy’s but costs half as much—an observation that makes Venetian real-estate agents pray to Saint Mark with renewed fervor. Yet beyond the terracotta roofs and Game-of-Thrones gift-shop tedium, this nation of 3.8 million has become the Adriatic’s equivalent of that over-achieving cousin who shows up to Thanksgiving with a hedge fund, a tan, and unsettling war stories.

Croatia joined the eurozone on 1 January 2023, swapping the kuna for the euro with the casual air of someone exchanging beach towels. For Berlin and Brussels, the move was geopolitical Feng Shui: another slab of Balkan concrete bolted to “core Europe,” thereby delaying the day when populists start redrawing borders with crayons and blood. For locals, prices rose 12 percent overnight, proving once again that monetary union is just gentrification with a central bank.

Globally, the switch matters more than the GDP spreadsheets admit. Croatia is now the EU’s southeastern pressure valve; when African or Middle Eastern migration routes shift, Zagreb’s border police become Brussels’s bouncers, complete with riot gear and a Spotify playlist titled “Fortress Europe.” Meanwhile, Russian oligarchs—freshly evicted from Kensington—have discovered that Dalmatian villas offer the same money-laundering potential as Mayfair, plus the bonus of a 200-year-old olive tree in the garden. The G7 nods approvingly: better Dubrovnik than Dubai.

Climate change has turned the country into a living postcard of the apocalypse. Last summer, wildfires licked the outskirts of Split while cruise ships idled offshore, engines humming like impatient private-equity partners. The same heatwave that crisped Croatian pine forests also melted Alpine glaciers, pushing European tourists southward like sunscreened lemmings. UN climate negotiators now cite Croatia’s scorched vineyards as exhibit A in their PowerPoint titled “We Told You So, 1997–Present.” Economists, never ones to waste a good catastrophe, have rebranded the country as a “climate-resilience lab,” which is consultant-speak for “come watch us try not to burn down your vacation.”

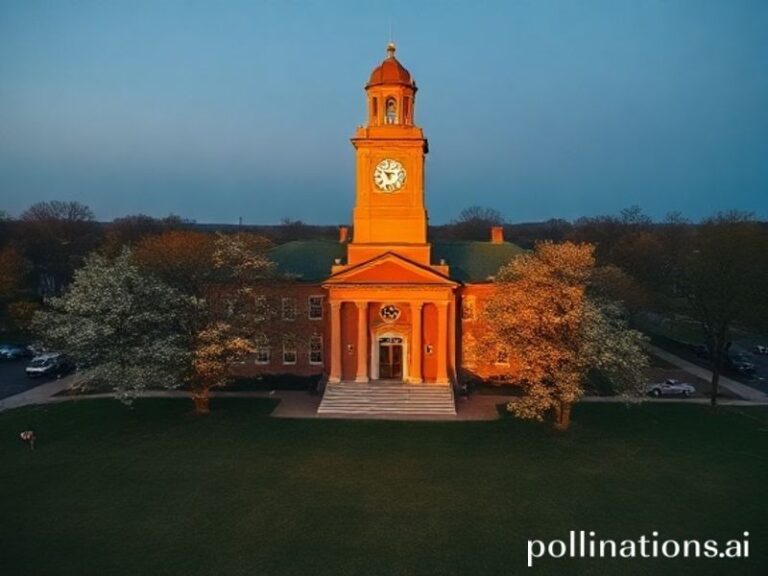

On the digital frontier, Croatia’s Rimac Automobili produces electric hypercars that accelerate faster than a hedge-fund divorce. When the company floated on Nasdaq this year, it briefly made founder Mate Rimac wealthier than the entire nation’s annual defense budget—an irony not lost on a country that still remembers when its tanks were Tito’s hand-me-downs. Silicon Valley VCs now pronounce Zagreb with the same reverence they once reserved for Tallinn, proving that post-Soviet branding has a half-life shorter than a TikTok trend.

The football team, runner-up in the 2018 World Cup and third in 2022, functions as the country’s most successful diplomatic corps. When Luka Modrić threads a pass, global television audiences momentarily forget the nation’s 1990s soundtrack of artillery. FIFA’s soft-power accountants estimate that each Croatian counterattack earns roughly €30 million in positive media coverage, a valuation that makes the foreign ministry consider replacing its press officers with midfielders.

All of this happens under the long shadow of demographics. Croatia loses a small town’s worth of citizens every year to Dublin buses and German factories, prompting government slogans like “Come Back, We Have Broadband Now.” The diaspora wires home €2 billion annually, effectively crowdfunding national solvency one Frankfurt bartending shift at a time. Should the trend continue, analysts predict Croatia will evolve into Europe’s first fully automated coastline: empty villages run by AI concierges serving German retirees who still mispronounce “Hvala.”

And yet, against the odds, the experiment endures. NATO’s newest member guards the alliance’s soft underbelly with aging MiGs and brand-new optimism. EU recovery funds—€6.3 billion of Brussels’s guilt money—are paving highways that locals joke will finally allow them to flee the country more efficiently. In a world addicted to superlatives, Croatia remains refreshingly medium: medium-sized, medium-rich, medium-cynical. It is the rare country that knows its own punchlines—and still laughs, because the alternative is to cry into the Adriatic, and the salt water is already warm enough.