Martina Navratilova: How a Cold-War Defector Served Aces Against the World Order

Martina Navratilova: The Defector Who Beat the World at Its Own Game

by Dave’s International Desk

Prague, 1975. Somewhere behind the Iron Curtain, an 18-year-old left-hander with a serve like a guillotine and a mullet that mocked the very concept of aerodynamics decided she’d had enough of velvet revolutions and state-sponsored haircuts. She slipped out the back door of a tournament hotel in New York, applied for U.S. political asylum, and—voilà—Martina Navratilova became the Cold War’s most elegant piece of sporting contraband. The Czechoslovak regime promptly revoked her citizenship, which was ironic because citizenship had never really granted her much in the first place—except maybe the right to stand in bread lines with a tennis racket slung across her back like a dissident’s guitar.

Fast-forward four decades and the same woman is now a passport-carrying citizen of the globe: American by paperwork, Czech by birth, British by marriage (to a woman who once sold her a house—only in the free market could romance begin with a property deed), and, unofficially, an honorary citizen of every country that enjoys watching its own national hero get dismantled on Centre Court. She ended her career with 18 Grand Slam singles titles, 31 doubles majors, and a mixed-doubles haul so large it could be used as ballast on a cargo ship. The numbers are obscene, really—like counting how many times humanity has clicked “Agree” without reading the terms.

Yet Navratilova’s real legacy isn’t the silverware; it’s the way she weaponized excellence against every phobia the 20th century had on offer. She beat sexism (prize money parity? she sued for it), homophobia (came out in 1981 when “LGBTQ” sounded like a rogue Scrabble hand), and nationalism (she played Fed Cup for the U.S. while still speaking Czech to her coach, a linguistic two-finger salute to every border guard who ever asked for papers). If you listen closely during Wimbledon fortnight, you can still hear the ghost of Margaret Court muttering about “traditional values” while being steamrolled 6–2, 6–1 in the 1987 final.

On the geopolitical stage, her story reads like a satirical novella the CIA wished it had commissioned. A Soviet-bloc athlete defects, wins the West’s most bourgeois tournaments, becomes an icon of capitalist fitness culture, and then—because irony never sleeps—returns to her newly capitalist homeland as a celebrity, where Prague cafés now sell “Martina Power Smoothies” for the equivalent of a week’s salary in 1975. The Berlin Wall fell, but Navratilova had already jumped it in tennis shoes.

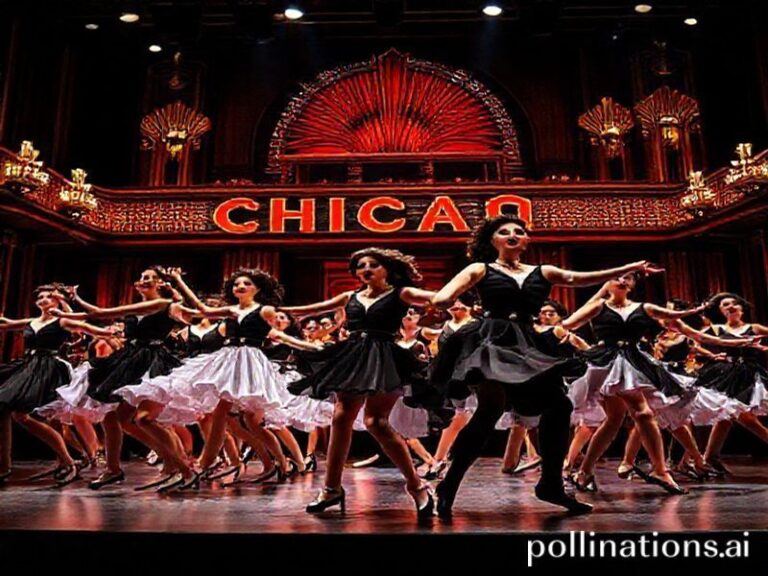

Off court, she’s been busy reminding the world that athletes are not decorative action figures. She’s campaigned for refugees, clashed with Twitter’s algorithmic outrage machine over trans athletes in women’s sport (proving that nuance is the first casualty of 280 characters), and appeared on reality TV—because even legends need a retirement plan that isn’t just Wheaties boxes. Watching her cha-cha on Dancing with the Stars was like seeing Che Guevara do the Macarena: ideologically confusing, mildly hypnotic, and ultimately proof that revolutions evolve into salsa steps if you wait long enough.

And so the arc of Navratilova bends toward a very modern paradox: hailed everywhere, owned nowhere. The Czech Republic gave her a passport again in 2008, but the gesture felt like an ex sending a “you up?” text thirty years after the breakup. Meanwhile, the U.S. has claimed her as proof that immigration builds champions—conveniently glossing over the part where she wouldn’t have needed to immigrate had the Cold War been a slightly less ridiculous dick-measuring contest. Britain tolerates her commentary on the BBC, partly for insight, partly for the sheer novelty of hearing someone describe a double fault as “an unforced error on the scale of Brexit.”

In the end, Navratilova’s biography is a cautionary tale for anyone who still believes sports are apolitical. She turned tennis into a passport stamp, a protest sign, and a punch line—often all at once. The world keeps trying to file her under “Czech,” “American,” “lesbian,” “champion,” or “controversial.” She keeps winning the point by refusing to stay inside any single baseline. That, dear readers, is how you beat the house in a game rigged by nations, hormones, and history: you serve an ace so hard the net forgets which side it’s supposed to be on.