From Glasgow to Global Guffaw: How Billy Connolly Weaponized Laughter Against Dictators and Dullness

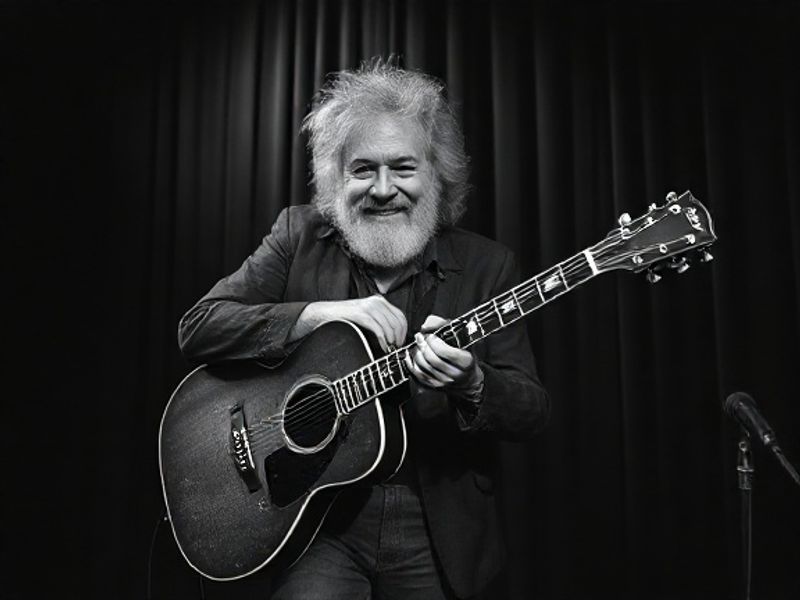

There was a moment—around the time the Berlin Wall was still chucking chunks of concrete at history’s shins—when a Glasgow shipyard welder-turned-banjo-strumming-folk-singer strode onto a London stage and essentially annexed the English language for his own comic empire. Sir William Connolly, CBE, knight-errant of the one-liner and hair like a dandelion that’s seen things, was busy proving that geopolitics can be distilled into a punchline about an inflatable brassiere. The world laughed, then quietly filed it under “soft-power diplomacy.”

From Melbourne to Montreal, Connolly became the unofficial ambassador of “speak your mind before it’s outlawed.” In the 1970s, while the Cold War was busy stockpiling mutually assured punch-ups, Connolly was exporting a different WMD—Weapon of Mass Derision. Soviet dissidents bootlegged his vinyl; South African students hid his cassettes behind copies of the Afrikaans Bible; even the CIA, not known for its sense of humor, reportedly studied his timing to see if sarcasm could be weaponized (it couldn’t; they tried it on Congress and everyone just assumed it was a regular hearing).

The broader significance? Connolly’s comedy was a Trojan horse filled with Glaswegian candor. He slipped in discussions of sectarianism, sexual mores, and the sheer absurdity of human existence disguised as a shaggy-dog story about a fart in a spacesuit. When he joked that “Scottish kleptomaniacs take things literally,” global audiences learned, almost by accident, that regional identity could be both fiercely parochial and universally exportable—an early masterclass in glocalization before marketing departments ruined the word.

Meanwhile, dictatorships attempted to ban him, which is always the surest sign you’ve gone international. The Ayatollah’s censors declared his 1983 stand-up “corrupting,” presumably because no mullah cared to explain what a “jobby wee” was to the Revolutionary Guard. In Pinochet’s Chile, bootleg VHS tapes circulated like samizdat, their tracking lines warbling like a nervous witness. The joke, it turns out, is mightier than the junta—though slower; punchlines rarely outrun bullets.

Fast-forward to the streaming era, and Connolly’s back catalogue suddenly sits next to Korean soap operas and Nigerian noir on the same algorithmic shelf. His face—now etched by Parkinson’s into a kind of geological map of mirth—appears in documentaries where he retraces the Scottish diaspora, reminding Canadians and New Zealanders alike that their ancestors fled misery only to replicate it in nicer weather. The irony isn’t lost on him; he narrates it with the wry grin of a man who’s realized the planet is just one extended open-mic night with occasional genocide.

Globalization giveth and globalization taketh away: Connolly’s gags about Catholic guilt now compete for attention with TikTok priests consecrating sourdough. Yet the underlying transaction remains—audiences still crave the catharsis of hearing someone articulate the cosmic joke they’ve always suspected was on them. In that sense, Connolly is less a comedian than a low-cost therapist with a banjo, charging only the price of a streaming subscription and your remaining attention span.

And so, as COP delegates argue over the precise temperature at which irony becomes lethal, and AI-generated stand-up bots learn to replicate Glaswegian vowels without the trauma that forged them, Connolly ambles onstage with a walking stick and a grin that says, “Yes, dear, we’re all doomed, but have you heard the one about the inflatable brassiere?” The world leans in, united for three minutes by the possibility that collapse itself might be faintly ridiculous.

In the end, Sir Billy’s legacy isn’t measured in YouTube views or knighthoods—it’s in the quiet recognition that laughter is the last passport no government can revoke, stamped indelibly every time someone in a language you don’t speak collapses at the phrase “there’s been a murrrderrr.” Globalization may have given us supply-chain snarls and billionaire space races, but it also gave us a Scottish prophet reminding the species that if we’re going down, we might as well go down heckling.