Scorpion on the World Stage: How René Higuita Flipped Gravity and Globalization in One Audacious Move

Scorpion in a Suitcase: How René Higuita Accidentally Became the World’s Most Dangerous Tourist

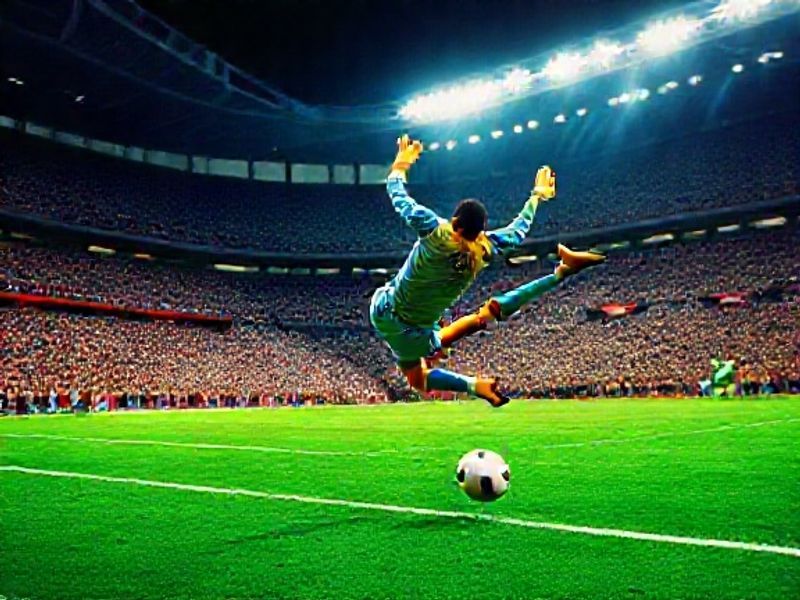

By the time the Berlin Wall had been reduced to souvenir fragments, René Higuita was busy turning the penalty area into a geopolitical playground. The Colombian goalkeeper—part acrobat, part liability insurer’s nightmare—never bothered to wait for history’s permission slip. Instead, he chose 1990, that giddy year when Francis Fukuyama was busy declaring everything “over,” to unveil a move that would have made Marx, Engels, and probably the entire Bundesbank drop their bratwurst: the scorpion kick. A global audience watched, half-awed, half-horrified, as Higuita let his feet fly overhead like a Cold-War surplus missile doing interpretive dance. The ball was cleared; the metaphor lingered.

International significance? Absolutely. Higuita’s stunt arrived just as satellite dishes were sprouting across Europe like post-Thatcher mushrooms, piping Colombian league highlights into living rooms that had previously considered South America a vague rumor involving coffee and kidnappers. Suddenly, every suburban teenager from Liverpool to Ljubljana was attempting scorpion kicks on asphalt, shattering tibias and parental dreams in equal measure. Orthopedic surgeons in Milan quietly updated their vacation homes; FIFA quietly updated its liability forms. Globalization, it turned out, could fit inside a six-yard box and still leave room for existential dread.

Off the pitch, Higuita’s life read like a Netflix true-crime series that even Netflix deemed “a bit much.” There was the friendship with Pablo Escobar—because nothing says “sound career guidance” like bonding over mutual appreciation for elastic goalkeeping and narco-aesthetics. There was the seven-month stint in Bogotá’s Modelo Prison for facilitating a kidnapping negotiation, a charge that sounds less like jurisprudence and more like an avant-garde theatre workshop. Amnesty International politely looked the other way; Nike, ever the opportunist, briefly considered a “Just Do the Time” campaign before cooler legal heads prevailed.

Yet the world kept watching, because Higuita embodied a wider anxiety: the suspicion that the 1990s would be less about “the end of history” and more about history’s unpaid bar tab finally arriving with interest. Colombia itself was a case study in what happens when Cold-War proxy wars discover cocaine margins; Higuita was simply the goalkeeper tasked with saving shots while the stadium’s foundation dissolved into narco-limestone. When he hoofed a clearance into the stratosphere, viewers from Jakarta to Johannesburg recognized the gesture: the universal human desire to punt one’s problems into orbit and hope insurance covers re-entry.

The 1994 World Cup provided the inevitable tragicomic epilogue. Higuita’s kamikaze dribble against Cameroon—think Franz Kafka rewriting “The Very Hungry Caterpillar”—gifted Roger Milla an open-net winner and Colombia an early flight home. Back in Medellín, defender Andrés Escobar (no relation to Pablo, though the universe clearly enjoys dark punchlines) was murdered days later for an own goal. Higuita, newly released from prison, attended the funeral wearing sunglasses indoors, which is either grief or brand management—sometimes the lighting is just that bad.

Still, the myth refused to die. In 2020, when a pandemic forced humanity indoors, viral clips of the scorpion kick resurfaced as a reminder that physical impossibility is merely a suggestion. Children in lockdown from Lagos to Los Angeles tried the move on living-room carpets, prompting a 300% spike in household lamp casualties. Insurance companies, still scarred from the first wave, quietly updated actuarial tables under the subheading “Higuita Clause.”

Today, as FIFA expands the World Cup to 48 teams—because nothing solves corruption like more revenue—Higuita roams the after-dinner circuit in a blazer two sizes too shiny, selling anecdotes to corporate audiences who chuckle nervously at prison jokes. He remains a walking allegory: the entertainer who risked everything, lost most of it, and somehow still ended up the sanest person in the room. In a world where billionaires rocket themselves just shy of orbit and call it progress, the scorpion kick feels almost quaint—a moment when danger was still handmade and gravity hadn’t yet unionized.

Conclusion: René Higuita didn’t just save goals; he saved us from the illusion that the global village would be governed by reason. Instead, he offered a simpler truth: sometimes the only rational response to chaos is a backward flip and a prayer, ideally with good camera angles. History may not repeat itself, but it definitely practices scorpion kicks when nobody’s looking. Wear shin guards.