Stephen King: How America’s Maine Export Conquered the World’s Nightmares

Stephen King: The Last American Export That Doesn’t Require a Shipping Container

by our world-weary correspondent, filing from a mildewed motel somewhere east of everywhere

He’s sold more than 500 million books, been translated into 60-odd languages, and inspired a global cottage industry of night-lights, therapy sessions, and clowns seeking safer career paths. Yet Stephen King remains, curiously, the United States’ most durable soft-power asset—more reliable than democracy summits, less leaky than Patriot-class submarines, and considerably cheaper to maintain than an aircraft-carrier strike group. While Washington debates tariffs and TikTok bans, King quietly colonizes the planet’s bedside tables, proving that fear, like cholesterol, travels border-free.

Consider the optics. In Seoul subway cars, salarymen scroll through It on phones bright enough to illuminate their own existential dread. In São Paulo, favela libraries display dog-eared copies of The Shining next to Portuguese editions of self-help gurus who promise the exact opposite outcome. Even in Tehran—where the morality police frown on un-Islamic horror—bootleg PDFs of Pet Sematary circulate like samizdat, proving that nothing unites humanity quite like the suspicion that the family pet is plotting revenge from beyond the grave.

The global appeal is, of course, deeply ironic. King writes almost exclusively about Maine, a state whose population could fit into a mid-tier Manila barangay with room left over for the moose. Yet his microcosmic towns—Derry, Castle Rock, Jerusalem’s Lot—function as universal stand-ins for every backwater where broadband is patchy and the past refuses to stay buried. Swap the maple syrup for palm toddy, replace the lobster traps with rice paddies, and the underlying dread still scans. The human condition apparently ships well.

Critics love to dismiss King as genre comfort food, but that misses the geopolitical utility of his nightmares. In an era when actual headlines read like rejected first drafts—killer clowns elected to high office, pandemics that refuse the courtesy of zombies, billionaires cosplaying space explorers—King’s brand of synthetic terror provides a useful control rod. Readers from Lagos to Ljubljana can turn the page and think, “Well, at least my town isn’t haunted by a shape-shifting spider wearing silver balloons.” The horror is safely outsourced, which is more than can be said for inflation.

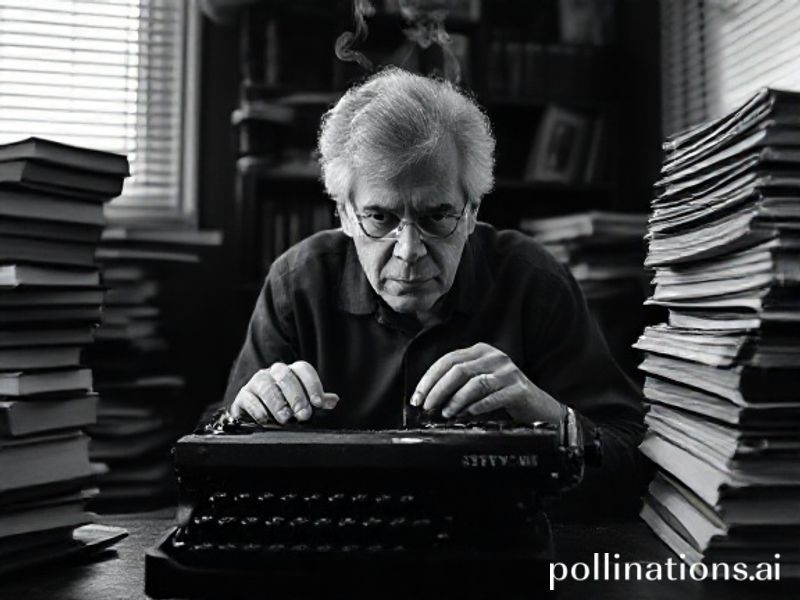

The economic footprint is no joke. Hollywood’s addiction to King adaptations props up the sagging Los Angeles dream factory the way cheap fentanyl props up a Midwestern mall. Each remake—from India’s cellphone-centric adaptation of Cell to Japan’s surprisingly polite version of Misery—keeps regional crews employed and streaming platforms knee-deep in bingeable dread. Meanwhile, the man himself still bangs away on a vintage laptop in Florida, a state that already resembles a deleted scene from The Stand, proving that location scouting is for amateurs.

Soft power analysts note that King offers something Silicon Valley never managed: an emotional operating system that runs equally well on dial-up or 5G. Try explaining Facebook’s metaverse to a rice farmer in Uttar Pradesh and you’ll get blank stares; mention a killer car named Christine and the man nods knowingly—he’s met that automobile, or at least its cousin. Horror, it turns out, is the universal translator Big Tech promised but never delivered.

What does it mean that the most widely shared American mythos now involves possessed hotels, telekinetic prom queens, and dogs that refuse to stay in the yard? Perhaps only that the empire, having exhausted its supply of optimism, is monetizing its nightmares at scale. While the State Department issues travel advisories, King sells the fear back to us in paperback, hardcover, audiobook, and limited-series event—complete with British actors doing passable New England accents. It’s the sort of soft-power coup that makes the British Council’s Shakespeare outreach look quaint, if not positively cuddly.

In the end, King’s global reign may outlast the republic that spawned him. Long after the last McDonald’s has been repurposed as a solar-powered falafel stand, some teenager in Ulaanbaatar will still be discovering the cosmic terror of Pennywise. That’s the thing about fear: it doesn’t need a passport, it never overstays its visa, and—unlike democracy—it rarely asks for receipts.