Global Rangers: The World’s Underpaid Firewall Between Us and Ecological Collapse

Across the planet, “ranger” is less a job description than a Rorschach test. Say it in Nairobi and you picture a Kenya Wildlife Service officer politely asking an irate elephant to please not flatten the minister’s convoy. Whisper it in Warsaw and it conjures a camouflaged forest ghost monitoring Belarusian drones for the EU’s nervous eastern fringe. In Los Angeles it still means a khaki-clad Instagrammer lecturing influencers about feeding coyotes gluten. One word, many costumes, same punch-line: someone must stand between what humans want right now and what will still exist tomorrow—usually while being paid in exposure or, if they’re lucky, a stipend large enough for instant noodles.

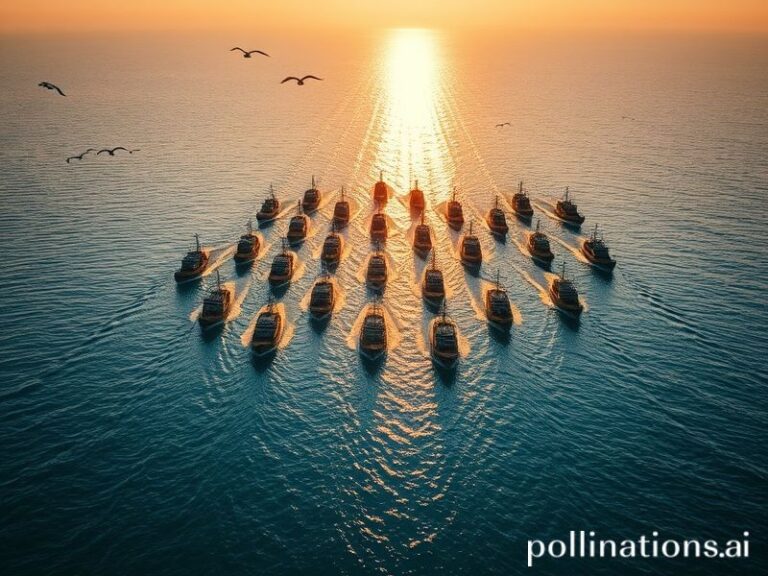

The global ranger economy is a masterpiece of bureaucratic origami. The UN counts 150,000 “official” rangers worldwide, a figure so precise it’s obviously fictional, like a dating-app height. Add community scouts, private security, mercenary “eco-commandos,” and the occasional heavily armed ornithologist, and you’re looking at a shadow force roughly the size of the French army. They guard 15% of Earth’s land surface, 7% of the oceans, and 100% of our guilty consciences. Their budgets, meanwhile, are assembled like a ransom note: scraps of tourism revenue, carbon-credit IOUs, NGO tote-bag sales, and the spare change rich countries drop while patting themselves on the back at COP summits.

Technology was supposed to liberate rangers from the Stone Age—an upgrade from “walk until blisters bleed” to “drone feeds and satellite pings.” In practice, the drone crashes into the canopy, the satellite subscription lapses when the finance ministry discovers embezzlement, and the ranger ends up back on foot, updating the poachers’ movements via WhatsApp voice note while praying the data bundle lasts. Meanwhile, Silicon Valley sells the same governments AI-powered “conservation analytics” that identify endangered species with 97% accuracy and zero sense of irony as the animals vanish.

Then there’s the geopolitical layer. In the Sahel, rangers moonlight as counter-terror auxiliaries; a ranger who began the year counting addax antelope finishes it counting bullet casings after jihadists discover rhino horn funds Kalashnikovs. Conversely, in the South China Sea, Chinese “coast-guard rangers” plant flags on reefs that were fish yesterday, islands today, and aircraft carriers tomorrow—proving that conservation is merely imperialism with better PR. The Americans, never outdone, have dispatched retired special-forces types to “advise” rangers in Latin America, presumably because nothing deters illegal logging like the lingering scent of 1980s regime change.

Climate change has turned rangers into reluctant eschatologists. They now track not just poachers but shifting treelines, glacier retreat, and the awkward moment when the last polar bear realizes the ice was never coming back. In Australia, rangers conduct “controlled burns” that feel increasingly like rehearsals for the actual apocalypse. In the Amazon, they catalogue species faster than Bolsonaro can auction the forest, a macabre race that makes Schindler’s List look upbeat.

And yet, for all the doom, rangers remain the planet’s most stubborn optimists. Ask a ranger in Virunga why he still reports for $200 a month while rebels trade bullets over gorilla habitat, and he’ll shrug: “Someone has to remember tomorrow.” It’s the sort of line that sounds heroic until you realize it’s also a job description for every underpaid intern holding civilization together with duct tape and delusion.

Conclusion: In the end, rangers are humanity’s collective attempt to hire a babysitter for a house already on fire. We arm them with slingshots, ask them to put out the flames, and then act surprised when they ask for a raise. Whether they wear green fatigues, navy camo, or a Patagonia fleece, they are the thin khaki line between our voracious present and whatever future we haven’t sold yet. The gig doesn’t come with dental, but at least the commute—through charred forests, mined savannahs, and drowned coastlines—is scenic. For now.