Global Energy Chess: Meet the Landman Who Owns Half the Planet Beneath Your Feet

The Landman Cometh: How a Mild-Mannered Leasing Agent Became the World’s Most Wanted Middleman

By Dave’s International Affairs Desk

Mention the word “landman” in Houston and you’ll be offered a bourbon and a non-disclosure agreement. Whisper it in the Niger Delta and someone will check for drones. Say it at a Berlin climate summit and security will politely escort you to the compost heap. Yet this unassuming profession—part genealogist, part repo-man, part travelling salesman of subterranean rights—has quietly become the oil-soaked thread stitching together half the planet’s geopolitical sweater. Pull it, and the whole itchy thing starts to unravel.

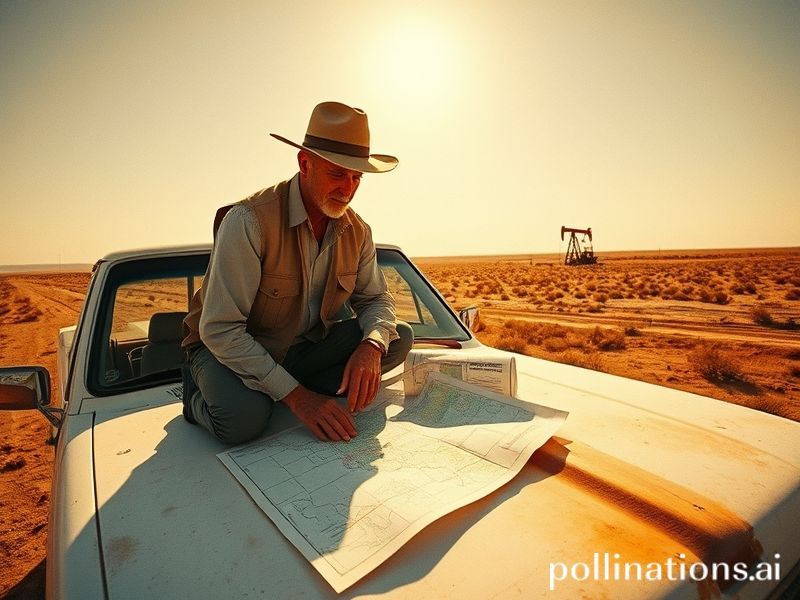

A landman’s job, at least on paper, is refreshingly transactional: convince farmers, widows, chiefs, or entire ministries that the sludge beneath their feet is worth a signature and a cheque. Historically, that meant knocking on doors in West Texas with a briefcase full of lease forms and a smile calibrated to “trust me, I’m from headquarters.” Today, the same profession spans continents, currencies, and, increasingly, war-crime statutes. The modern landman might breakfast on katsudon in Tokyo (liquefied-natural-gas port approvals), lunch on koshary in Cairo (offshore Red Sea blocks), and end the day Zooming into a Yamal Peninsula reindeer-herding collective whose dialect has forty-three words for “permafrost” but none for “sovereign wealth fund.”

Globalization turned the landman from local fixer into international necromancer. Where once he sweet-talked ranchers, he now ghostwrites environmental-impact statements in four languages, lobbies parliaments with briefcases of “capacity-building grants,” and interprets election results the way other people read racing forms. The upside? A single signature can reroute tankers through the Strait of Malacca faster than any admiral. The downside? Same signature can also reroute refugee flows, interest rates, and the career prospects of energy ministers who believed the brochure.

Consider the choreography: In Mozambique, French and American landmen recently competed—politely, behind tinted glass—to lease the same fishing village twice, once for offshore LNG and once for a floating solar array the locals mistook for an aircraft carrier. In Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale patch, landmen now arrive with social-media teams who livestream indigenous ceremonies for “community engagement,” then geo-tag sacred sites for fracking grids. Nobody is rude enough to call it colonialism 5.0, but the Wi-Fi password on the corporate jet is literally “ManifestDestiny_2GHz.”

The profession’s moral flexibility is matched only by its wardrobe. Standard issue is a Patagonia vest in Houston, a bullet-proof blazer in Baghdad, and, for Scandinavian assignments, a knitted sweater woven from recycled shareholder reports. Ironically, the only constant accessory is a nondisclosure agreement thick enough to staunch a pipeline rupture. In a world allergic to paper trails, the landman’s briefcase is the last honest forest left standing—before it’s pulped for indemnity clauses.

International watchdogs have noticed. The European Parliament now holds “Landman Appreciation Days” (their phrase, not ours) where MEPs practice saying “force majeure” without giggling. Meanwhile, China’s Belt-and-Road initiative employs its own landmen—state geologists in better suits—who swap mineral rights for ports, railways, and the occasional parliament cafeteria naming rights. The result is a planetary shell game where the pea is always oil, the cups are sovereign borders, and the dealer speaks perfect legalese.

Yet for all the cynicism, the landman remains humanity’s most honest broker of contradiction. He promises prosperity while preparing evacuation routes. He quotes scripture to Baptists and shareholder primacy to atheists. In Ukraine’s Donbas region, landmen currently juggle leases that may be under Russian, Ukrainian, or, by Thursday, Luxembourgian jurisdiction—depending on artillery trajectories. Somewhere in that paperwork is a farmer whose beetroot field is simultaneously an EU carbon sink and a Moscow tax write-off. If that isn’t magical realism, what is?

Conclusion

So here we stand: an overheating planet, a global energy chessboard, and a single profession holding the deeds to half the squares. The landman’s future looks bright—phosphorescent, really, like the flares over a refinery at midnight. Expect to see him at COP summits swapping drill bits for carbon credits, or at Davos hawking geothermal futures to crypto-moguls who just discovered Iceland. And if civilization collapses before the last barrel is pumped, well, someone will need to lease the fallout shelters. Odds are he’ll arrive early, smile polished, NDA in hand, ready to explain why the apocalypse comes with a signing bonus. Just remember to read the fine print; the afterlife may have extraction fees.