Open Stock: How the World Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Buying One Battery at a Time

Open Stock: The World’s Panic Pantry, or How We All Became Amateur Preppers

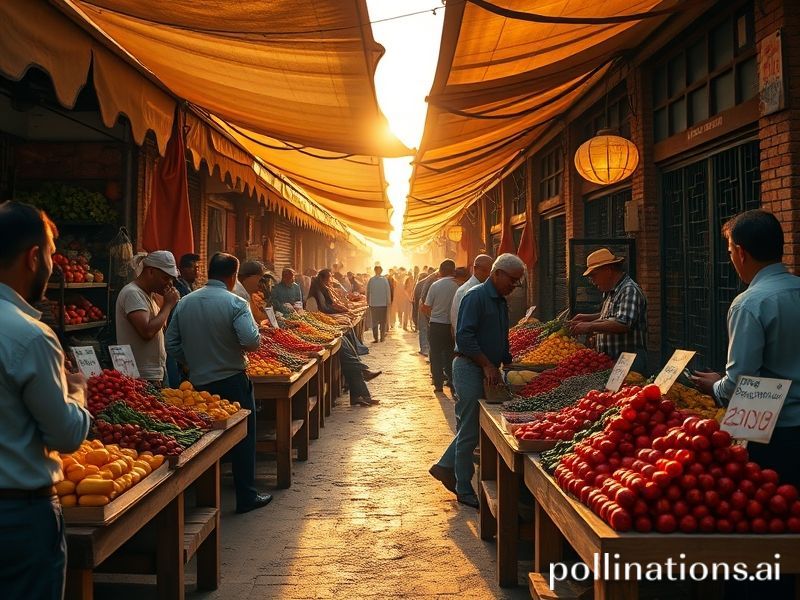

By the time you finish this sentence, someone in São Paulo will have panic-bought their fifteenth roll of industrial-grade aluminum foil, convinced the grid is about to collapse. That, dear reader, is the sound of “open stock” going global—an innocuous retail term meaning “items sold unpackaged, one by one” that has quietly mutated into a geopolitical mood ring. From Warsaw wet markets to the fluorescent aisles of a suburban Tokyo Don Quijote, the same scene repeats: shelves once ordered by brand and country of origin now resemble a UN buffet after the delegates have fled. Loose batteries from Malaysia mingle with single Bulgarian light bulbs, orphaned Korean face masks flirt with Ghanaian tomato paste. It’s consumerism’s last singles bar, and everyone’s too anxious to commit to a six-pack.

The pandemic taught the planet that supply chains are basically introverts: they snap under sustained eye contact. When container ships started playing bumper cars in the Suez and Shanghai went into yet another “temporary” lockdown, retailers discovered that selling things in tidy bundles was a luxury belief—rather like democracy or predictable rainfall. Open stock became the retail version of NATO Article 5: an attack on one SKU is an attack on all, so let’s just scatter the survivors and hope for the best.

In the European Union, open stock is now Brussels’ favorite euphemism for strategic autonomy. The Commission’s latest white paper—euphemistically titled “Resilient Single Unit Logistics”—quietly urges supermarkets to sell individual batteries so that when the next energy crisis hits, Europeans can hoard them like medieval indulgences. Meanwhile, Berliners trade rumors that loose AA Duracells are actually tiny American spies; in response, the French swear by a single rechargeable Eneloop “for the Republic.” Somewhere in Strasbourg, a bureaucrat updates an Excel sheet labeled “Civilizational Confidence Index” and sighs.

Cross the Pacific and the story darkens, as stories tend to do after a 14-hour flight in economy. Japan’s convenience stores—those shrines to immaculate packaging—now feature open-stock rice crackers sold in minimalist paper envelopes, each stamped with the face of a prefectural governor apologizing for inflation. The aesthetic is so refined that citizens queue for the privilege of paying 120 yen for what used to be the free sample. Capitalism, having run out of continents to exploit, is now monetizing the void between one cracker and the next.

Down in Lagos, open stock looks less like zen minimalism and more like pure hustle. Balogun Market has always functioned as the planet’s informal futures exchange: a single SIM card today can be half a router tomorrow, depending on the dollar-naira tango. Vendors sell phone chargers by the centimeter, snipping copper like goldsmiths. The UN calls this “micro-entrepreneurial resilience.” The traders call it Tuesday. Either way, Lagos survives global shocks because it never believed in the box in the first place.

Of course, where there’s loose merchandise, there’s also data—our era’s other open stock. Every lone battery sold via QR code feeds an algorithm in Shenzhen that predicts when your smoke detector will whimper for mercy. The World Economic Forum recently hosted a panel titled “Single-Unit Traceability for Planetary Health.” Translation: we’re one firmware update away from your fridge tattling on you for buying a solitary can of beans instead of the eco-friendly twelve-pack. Privacy, it turns out, was just another bulk discount we failed to appreciate.

So what does it all mean? Simply that civilization has rediscovered the ancient wisdom of the bazaar—just with worse lighting and existential dread. Open stock is the retail symptom of a world that no longer trusts tomorrow to look like today. It’s camouflage for inflation (pay the same, get less), therapy for control freaks (one unit at a time feels manageable), and a confession that the global conveyor belt is held together by duct tape and maritime insurance premiums we can’t afford to read the fine print on.

In the end, the joke is on us. We spent decades demanding choice, variety, the freedom to curate our identities one purchase at a time. Now the universe has granted that wish with malevolent precision: here’s a single roll of toilet paper, comrade—good luck curating your way out of the next shortage. And should you find yourself staring at a lone, unpackaged candle in a Caracas blackout, remember: it’s not just wax and string. It’s a votive offering to the gods of just-in-time logistics, flickering proof that the world is still open—for business, for speculation, for the small mercies we can still buy one fragile unit at a time.