Global Fallout: How Charlie Sheen Became the World’s Favorite Economic Indicator

Charlie Sheen: A One-Man Sanctions Regime the World Keeps Negotiating With

By “Lucky” Lucinda Marín, Senior Correspondent, Dave’s Locker

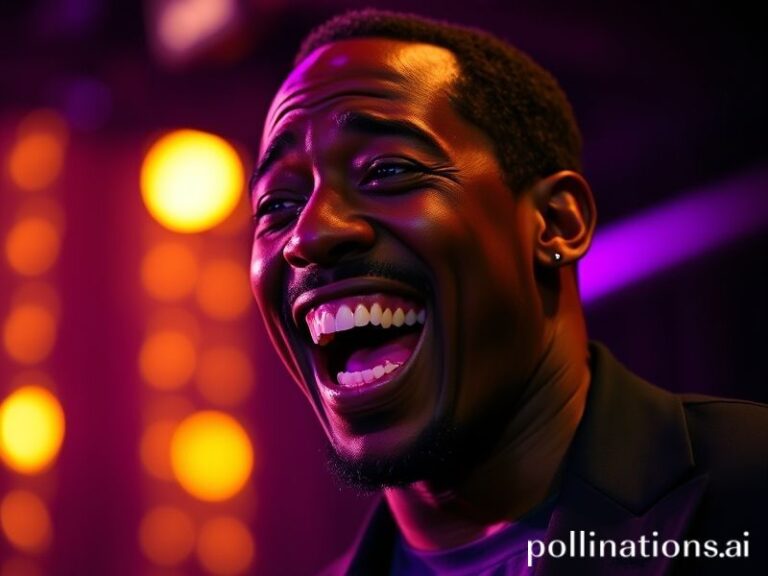

The name Carlos Irwin Estévez—better known to Interpol, hotel security cameras, and late-night subtitle writers as Charlie Sheen—functions as a sort of transnational Rorschach test. To Los Angeles he is an errant sitcom warhead; to Bangkok he is the cautionary tale that plays on loop in expat bars; to Berlin he is performance art so convincing that the city once considered giving him his own cabaret slot between the nihilists and the techno DJs.

When Sheen’s 2011 meltdown ricocheted across satellite feeds, foreign ministries from Ottawa to Canberra briefly wondered whether the phrase “winning” was a new strain of American soft power. It wasn’t. It was just the latest export of a country that packages self-immolation as prime-time entertainment and then sells the broadcasting rights back to the same planet that’s supposed to be horrified. The ratings, naturally, soared from Reykjavík to Riyadh, proving once again that schadenfreude is the only import the globe never slaps tariffs on.

Sheen’s career arc resembles a Bretton Woods agreement drafted after a three-day bender: early promise, reckless leveraging, abrupt default, followed by a series of restructuring talks conducted mostly on talk shows hosted by people who look faintly embarrassed to be fluent in English. Each continent has had to renegotiate its relationship with him. Latin America remembers the half-Hispanic kid who could have been its crossover king but instead became the telenovela villain you root for because at least he’s honest about the chaos. Europe, ever the connoisseur of American decline, treats him like a living Warhol print: mass-produced tragedy in neon colors, best appreciated while chain-smoking. Asia simply bootlegs the reruns and adds better CGI tigers.

The geopolitical irony is exquisite. While the United States spends trillions trying to convince the world it has its house in order, one barefoot Sheen wielding a machete of catchphrases on a Beverly Hills rooftop undercuts the entire narrative. Cable news in Seoul cuts to him whenever North Korea launches something; analysts argue that both phenomena are missiles, just aimed at different demographics. Meanwhile, the IMF quietly lists “Sheen volatility” as a risk factor for emerging markets—apparently nothing tanks the peso faster than the phrase “tiger blood” trending at the same time as your central-bank governor.

Human-resources departments from London to Lagos still use his interviews as training videos titled “How Not to Conduct a Performance Review.” Diplomats stationed in hardship posts swap Sheen quotes the way earlier generations swapped Churchill anecdotes, except Churchill never had to clarify whether the bottle or the microphone came first. Even the Vatican once convened a colloquium on modern excess; the working paper was titled “Two and a Half Sins: Sitcom Morality in a Post-Truth Era.” It concluded, with ecclesiastical shrug, that redemption arcs are easier to monetize when the sinner has good comic timing.

Sheen’s recent attempt at sobriety—documented, trademarked, and pre-sold to a streaming service near you—has been greeted abroad with the weary affection reserved for any aging empire trying to stage an intervention on itself. Canadians offer polite applause while quietly taking notes on copyright law; Australians place bets on relapse like it’s the Melbourne Cup; the French issue a Gallic sigh that translates roughly to, “Of course, but where is the chaos we fell in love with?”

And yet, for all the snickering, the planet keeps dialing him back in. Because deep down we understand that Charlie Sheen is not merely an American problem—he is globalization’s id, the part of the supply chain nobody wants to audit. He reminds every time zone that excess is a commodity, shame is negotiable, and the house always wins—except when the house is a rented mansion in the Hollywood Hills and the owner has misplaced the deed.

In the end, the world doesn’t need another lecture on American decadence; it needs a mirror. Sheen, in his cracked, unrepentant glory, holds one up—distorted, slightly blood-spattered, but undeniably reflective. We can cancel him, meme him, or cast him in a reboot nobody asked for. The ratings will still climb, the currencies will still fluctuate, and somewhere a customs officer will stamp a passport while humming the theme from Two and a Half Men.

Because if there’s one thing the international community agrees on, it’s that someone else’s chaos makes excellent background noise while we pretend to run the world.