Clint Eastwood: The Last Global Cowboy Riding Through Geopolitical Smoke

Clint Eastwood, the Man Who Shot the 20th Century and Winked at the 21st

by Dave’s International Desk

PARIS—Try explaining Clint Eastwood to a teenager who thinks “spaghetti western” is a TikTok pasta recipe. You’ll find yourself sounding like a Cold-War relic, extolling a lanky American who once lectured an empty chair at a political convention and still managed to book another studio deal. Yet from the neon canyons of Tokyo to the bullet-pocked suburbs of Sarajevo, Eastwood remains a sort of geopolitical Rorschach test: what you see in him usually reveals what you think about the United States itself—equal parts gun-smoke, guilt, and grandfatherly charm.

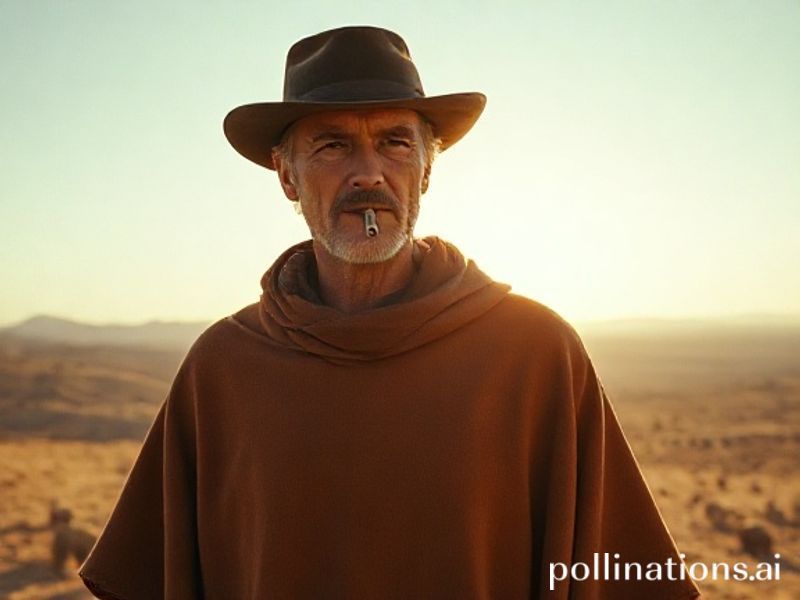

The Italians, naturally, claim partial custody. Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy—shot in Spain, financed by Germans, scored by a Roman—turned a bit-part TV cowboy into a pan-European fever dream of the American frontier. The poncho became a meme before memes existed; every Balkan flea market still sells knock-offs alongside fake Adidas and expired Kalashnikov ammo. Meanwhile, Japanese critics adore Eastwood’s minimalist acting style, calling it “mu-no-kyoku”—the blank melody—because nothing says Zen like a man who can kill six bandits while barely twitching an eyebrow.

In the Global South, the resonance is darker. During Argentina’s Dirty War, bootleg VHS tapes of Dirty Harry circulated as both entertainment and instruction manual for right-wing death squads. South African conscripts in the ’80s nicknamed their long-range rifles “Eastwoods,” a joke that aged like uranium. Even today, cartel TikTok accounts splice Narcos footage with Gran Torino clips, proving that nothing travels faster across borders than the fantasy of righteous violence—except, perhaps, the hangover of realizing it was never righteous to begin with.

Eastwood’s late-career turn toward self-lacerating guilt—Mystic River, Letters from Iwo Jima, Million Dollar Baby—plays differently abroad than at home. In Berlin, critics hail it as proof that even imperial empires eventually produce self-aware art. In Seoul, audiences parse the racial politics like an exam question: Is the Korean War veteran in Gran Torino a repentant racist or merely a sentimental one? The answer, like most things American, comes supersized and morally ambiguous, best consumed with popcorn and a shot of soju.

At 93, Eastwood still directs at a pace that shames filmmakers half his age, a fact that causes mild panic in European welfare states where retirement is treated as a constitutional right. French unions have considered flying him to Paris just to demonstrate what an 80-hour work ethic looks like; German engineers want to 3-D-scan his frontal lobe for efficiency hacks. Meanwhile, Hollywood accountants keep him on speed-dial because his sets finish on schedule, under budget, and without anyone having to apologize on Twitter—a miracle on par with water into Kombucha.

The global box office, of course, has moved on to multiverses where capes outnumber ponchos. Yet when American soft power needs a reboot, diplomats still trot out Unforgiven at cultural attaché screenings, hoping foreign audiences will confuse revisionist westerns with actual repentance for drone strikes. It rarely works, but the hors d’oeuvres are decent, and the subtitles conceal the awkward bits.

Which brings us to the ultimate irony: the same world that mocks U.S. gun culture keeps buying tickets to watch one man point a revolver and ask if we feel lucky. Perhaps the appeal lies not in the firearm but in the question itself—an existential dare wrapped in a smirk, delivered in a language everyone understands. In an era when nations outsource their wars to algorithms and mercenaries, Eastwood’s squinty moral calculus feels almost quaint, like rotary phones or the Geneva Conventions.

So here we are, orbiting a dying planet, streaming climate-disaster documentaries between Marvel trailers, and somehow the last cowboy still rides—if only in our collective algorithm, forever young, forever armed, forever on the verge of asking whether we’ve learned anything at all. The answer, as always, is probably no. But at least the poncho still fits.