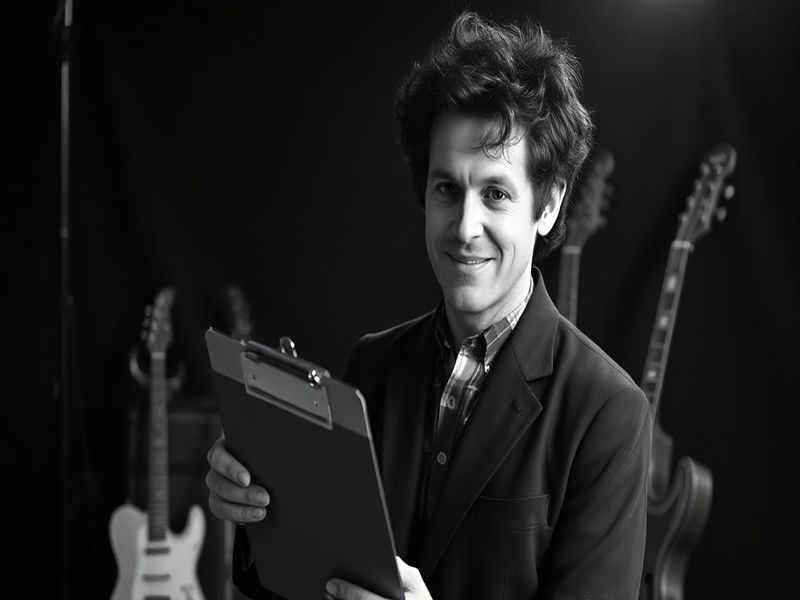

christopher guest

Christopher Guest, the man who taught the world that mockumentaries could be both devastatingly funny and uncomfortably accurate, has become something of a global patron saint for anyone who’s ever sat through a team-building exercise or watched a national leader try to play the ukulele on television. While his name rarely trends alongside geopolitical flashpoints, Guest’s influence seeps into international culture like cheap wine into a hostel mattress—subtle, persistent, and impossible to ignore once you notice the stain.

Born in New York City, raised between London and Los Angeles, and armed with a British peerage he never mentions unless cornered by etiquette journalists, Guest embodies the transatlantic confusion that now passes for cultural identity. It’s fitting: his films—This Is Spinal Tap, Waiting for Guffman, Best in Show—skewer institutions so precisely that diplomats could probably use them as training manuals. Indeed, one suspects the U.N. cafeteria occasionally screens A Mighty Wind just to remind staff what institutional self-delusion looks like in 4K.

The genius of Guest’s ensemble method—improvised scripts, deadpan delivery, escalating absurdity—has quietly colonized global television. South Korea borrows the format for its weekly political satire; German state broadcasters use it during Bundestag recess to reassure viewers that at least someone, somewhere, is still pretending to care about transparency. Even the Kremlin’s tame comedians have tried to replicate the Guest formula, though the jokes die faster than opposition journalists. One can picture Vladimir Putin watching Best in Show with the sound off, nodding sagely at the poodle choreography and wondering if he could introduce competitive dog grooming to Siberia.

The international resonance lies in Guest’s unflinching focus on micro-ambition. His characters don’t want to rule the world; they want to win a regional folk festival or get two percent better Wi-Fi in the RV. That pettiness translates. In Nairobi traffic jams, matatu drivers quote Spinal Tap’s amplifier scene at eleven. In São Paulo coworking spaces, startup founders recite Waiting for Guffman as if it were scripture, mostly because it is. The films remind us that the smaller the stakes, the louder the egos—a lesson every trade summit now confirms in real time.

There’s also a darker layer, visible only once you’ve binge-watched global news for a decade. Guest’s mockumentaries predicted the age of performative sincerity: politicians live-streaming themselves folding laundry, CEOs tearfully apologizing for algorithmic genocide while wearing Patagonia. We are all extras now in an endless Christopher Guest film, improvising lines about empathy while the planet quietly overheats. The only difference is that Guest’s characters eventually exit the frame; ours keep uploading.

So, what does the man himself make of this sprawling, unintentional empire? He’s characteristically elusive—married to Jamie Lee Curtis, holder of a hereditary barony he downgrades to “that silly title thing,” and reportedly spending his days composing bluegrass mandolin solos that will never appear on Spotify. In other words, he’s living the final act of one of his own films: the aging virtuoso who’s achieved everything and therefore finds nothing worth filming.

Conclusion: Somewhere between Brexit negotiations and the latest NFT art fair, Christopher Guest has become the unofficial chronicler of humanity’s chronic inability to recognize its own farce. His legacy isn’t just laughter; it’s the uncomfortable realization that the joke stopped being funny sometime around 2016 and is now simply documentation. If you listen closely at Davos, you can hear the faint twang of a banjo from A Mighty Wind echoing off the alpine slopes—a reminder that the absurdity was always multilingual, always bipartisan, and always, tragically, us.