mamdani

Mamdani: A Name That Travels—Sometimes with a Passport, Sometimes Without

By Our Man in Every Terminal Lounge

If you say “Mamdani” in a faculty club in New York, you’ll summon a polite nod to Mahmood Mamdani, the Ugandan polymath whose books on colonial ghosts and post-colonial hangover are heavier than the guilt in an IMF loan application. Whisper the same name in the back of a Nairobi taxi and the driver might assume you’re talking about the Mamdani estate, that gated citadel of aspirational concrete where the swimming pools glow turquoise at midnight and the private security guards salute you with the same enthusiasm they reserve for their next paycheck. Fly on to London, linger outside the School of Oriental and African Studies, and “Mamdani” becomes a battle cry for graduate students who quote his critique of humanitarian imperialism between sips of ethically sourced flat whites.

It’s a rare surname that can book itself three different flights without ever upgrading to business class.

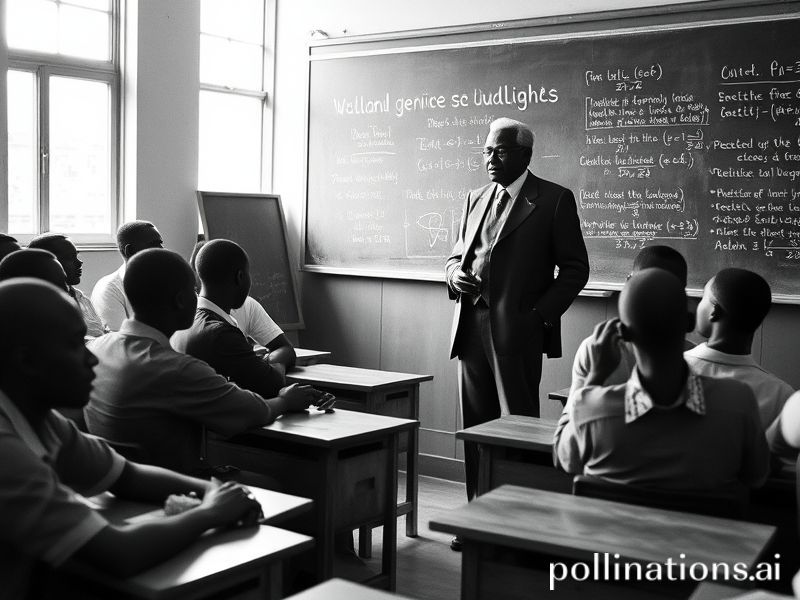

Mahmood Mamdani himself—born in Mumbai, raised in Kampala, expelled by Idi Amin, educated at Harvard, tenured at Columbia—has become the patron saint of itinerant intellect. His 1996 classic “Citizen and Subject” argued that indirect rule didn’t just leave Africa with lousy railways; it hard-wired a bifurcated state where one half of the population enjoyed rights and the other half received charity wrapped in tear gas. That thesis now reads like prophecy for anyone watching European border guards distribute bottled water to Syrian refugees before fingerprinting them into oblivion. The book has been translated into eleven languages, pirated in at least four, and summarized on TikTok by a 22-year-old in Jakarta who calls it “decolonize, bro.” Global relevance, meet global meme.

Meanwhile, the Mamdani brand—yes, there’s a brand—has quietly franchised itself across the Global South’s real-estate hunger games. The Mamdani Group, founded by Ugandan-Canadian tycoon Karim Mamdani, builds glass-and-steel temples to neoliberal aspiration from Kigali to Karachi. Their marketing brochures promise “five-star living with African soul,” which is corporate speak for Italian marble countertops and a playlist of Afrobeats in the elevator. Critics note the tragicomic symmetry: the name once synonymous with anti-colonial critique now sells penthouses overlooking golf courses irrigated by water rights expropriated from peasants who, in a different decade, might have read Mahmood’s books by kerosene lamp. History doesn’t repeat itself; it just flips the property deed.

On the diplomatic circuit, “Mamdani” has morphed into shorthand for a certain kind of cosmopolitan gravitas. When the UN needs someone to explain why today’s peacekeeping mission is tomorrow’s occupation, they fly in a Mamdani-esque expert—usually male, always eloquent, never in a hurry to catch the last chopper. The performance is so ritualized that seasoned correspondents play bingo: square one, “colonial legacy”; square two, “international community’s responsibility”; free space, “root causes.” The prize is a press badge and the creeping suspicion that we’re all unpaid extras in a sequel nobody green-lit.

Yet the name’s most subversive journey may be digital. Type “Mamdani” into an AI image generator and you’ll get a mash-up of mahogany bookshelves, safari sunsets, and vaguely pan-African textile patterns—algorithmic shorthand for “smart African person.” The machines have learned our lazy synecdoche; the joke writes itself while the royalties don’t. In a world where identity is keyword-optimized, even a surname can be SEO-gentrified.

So what does “Mamdani” mean on the 2024 geopolitical mood board? It’s a floating signifier with frequent-flyer miles: a reminder that ideas, capital, and branding travel faster than passports, often on the same plane but in different cabins. We use the name to indict empire, sell condos, or pad a conference panel, depending on the catering budget. And every time we do, the ghost of indirect rule updates its LinkedIn profile.

Which is only fitting. After all, in the global village, even irony has shareholders.