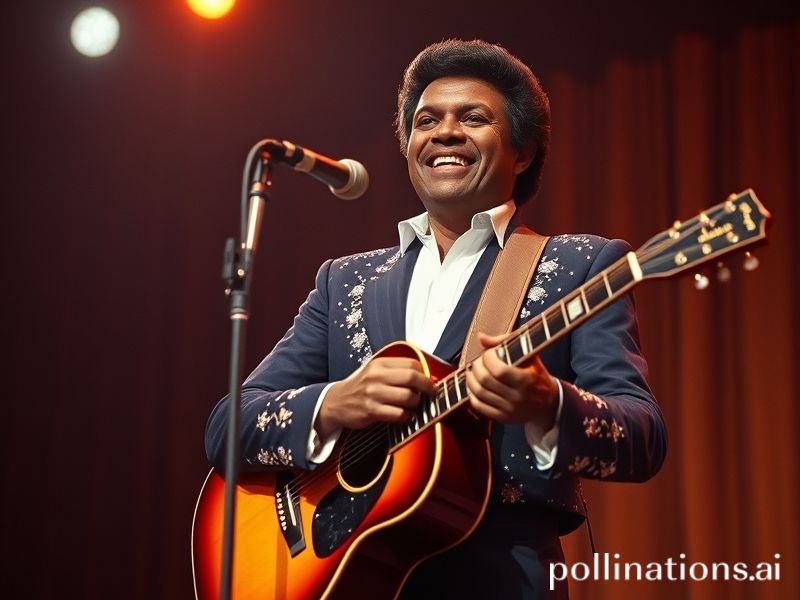

Charley Pride’s Final Encore: How a Black Cowboy Serenaded the Whole Damn Planet

In Dallas, they buried Charley Pride last Saturday, which is ironic because for most of the planet the man was never really dead—just filed under “miscellaneous American curiosities” between line-dancing and deep-fried butter. Yet the flags at half-mast in Pretoria, the tango-inflected “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin’” covers in Buenos Aires dive bars, and the sudden spike in Spotify streams in Jakarta all suggest the obituary writers may have underestimated how far a share-cropper’s son from Sledge, Mississippi can travel once the algorithm decides he’s palatable.

To understand the global ripple, start with the obvious: Pride was country music’s first Black superstar in a genre that spent decades marketing itself as the sonic equivalent of a whites-only Waffle House. While Nashville polished its rhinestone mythos, the rest of the world—busy with decolonization, dictators, and disco—mostly experienced country as either a punchline or the soundtrack to helicopter evacuations from Saigon rooftops. Pride’s velvet baritone slipped through anyway, carried by Armed Forces Radio, bootleg cassettes swapped in Lagos barracks, and those peculiar German tourists who collect Stetsons the way other people collect war crimes.

The symbolism was never subtle: a Black man singing about heartbreak and pickup trucks in a genre that once held segregationist rallies. To international ears, it sounded like America finally flirting with self-awareness—then immediately ghosting the morning after. Pride himself preferred laconic wit to sermonizing; when asked in apartheid-era Johannesburg how it felt being “country music’s Jackie Robinson,” he replied, “Jackie ran faster, but I get more encores.” The crowd laughed, because gallows humor is a universal language, especially when the gallows are still being assembled.

Meanwhile, the business side tells a darker joke. By the 1980s, Pride’s crossover appeal was so potent that Japanese execs flew to Nashville to bottle it. The result: karaoke machines loaded with “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone,” crooned by salarymen in Osaka who’d never seen a tumbleweed but knew existential despair intimately. The same machines later appeared in Iraqi karaoke bars circa 2004, where U.S. contractors belted Pride between mortar rounds, thus completing the circle of imperial absurdity: American culture conquers the world it can’t stop bombing.

The posthumous tributes have been predictably performative. The Country Music Association issued a statement praising Pride’s “barrier-breaking legacy,” conveniently forgetting the barriers they helped install. In Kenya, a DJ tweeted a Pride track with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatterNairobi, prompting a brief flame war over whether country music is “too white” to soundtrack anti-racist protests—an argument that neatly ignored Pride’s entire existence, which is perhaps the most American thing anyone could do.

And yet, in a year when global monoculture feels like a fever dream scripted by a bored AI, Pride’s death offers a rare honest note. His voice—warm, slightly amused, eternally road-weary—reminds us that globalization doesn’t always arrive wearing Nike swoosks or K-pop choreography. Sometimes it’s a Black man from Mississippi explaining heartbreak in four chords, translated into thirty languages, none of which can fully capture the irony of a genre built on rural white identity being saved from self-parody by a man whose family couldn’t vote until he was twenty.

So here’s to Charley Pride: proof that the empire’s cultural contradictions can occasionally harmonize, even if the empire itself remains off-key. He once sang, “I’d rather love you and lose you than never know your love at all,” a line that now sounds less like romantic resignation and more like the world’s relationship with America—equal parts infatuation and exasperation, doomed yet weirdly catchy. Somewhere tonight, a teenager in Seoul is learning that chorus on a cheap guitar, unaware that the cowboy hat she ordered online is stitched in Shenzhen, shipped through Dubai, and marketed via a Swedish streaming platform. If that isn’t country music in the 21st century—rootless, recycled, and inexplicably heartfelt—then nothing is.

Sleep well, Mr. Pride. The planet’s still humming your tune, even if half the listeners think “Merle Haggard” is a craft beer.