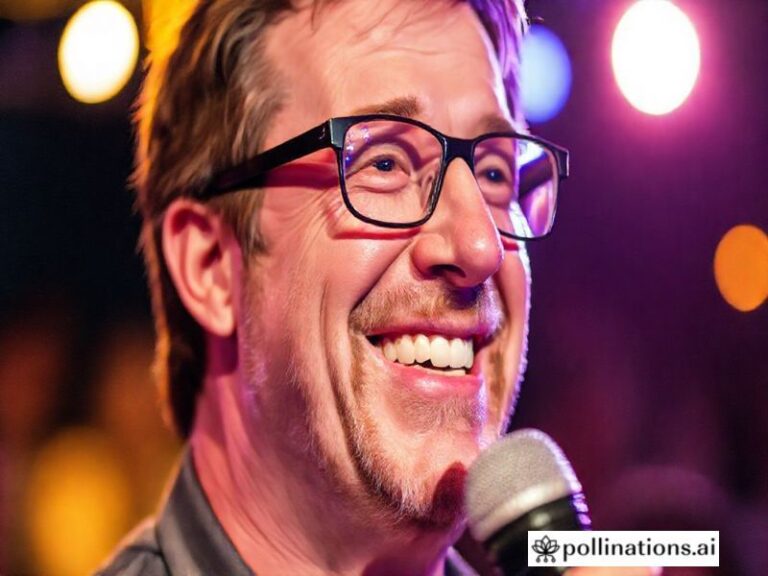

Tom Hardy: The World’s Last Functioning Soft-Power Missile

Tom Hardy: The Last Action Figure Standing Between Us and Global Thermonuclear Boredom

From the smoking rubble of what used to be called “cinema,” one man emerges wearing three layers of knitwear, a Bane mask repurposed as a tea-cozy, and the weary expression of someone who has just realized the Doomsday Clock is running on British Summer Time. Tom Hardy—actor, meme, walking dissertation on the decline of Western masculinity—has quietly become the most geopolitically significant English export since the Royal Navy sold off its last working aircraft carrier for scrap.

Consider the evidence. While NATO ministers argue over PowerPoint fonts, Hardy has already invaded seventeen international markets this fiscal year, armed only with a gruff whisper and the kind of jawline that could slice prosciutto at a G7 summit. In Seoul, teenagers queue overnight for early screenings of Venom 3: Maximum Carnage, Maximum Merchandise, Maximum Existential Dread. In Lagos, bootleg DVDs of Legend move faster than actual weapons. Meanwhile, somewhere in the Arctic, a Russian submarine captain queues up Mad Max: Fury Road on a cracked tablet, quietly wondering if Immortan Joe is really that much worse than his own chain of command. Soft power? Please. This is ballistic charisma.

Hardy’s global utility lies in his unique ability to play both predator and prey, often in the same scene. Watch him in The Revenant: half-man, half-meat-popsicle, dragging himself across frozen tundra while Leonardo DiCaprio gnaws on raw bison liver like a trust-fund survivalist. The symbolism is impossible to ignore—America devours everything in sight, while Britain limps along behind, bleeding but unbowed, muttering threats in an accent no subtitles can decode. Somewhere in Brussels, a Eurocrat watching the film on a long-haul flight jots “Tom Hardy = Article 5 deterrent?” in the margins of a trade-deal draft.

Of course, the man is also a walking Brexit metaphor: simultaneously cosmopolitan (he speaks French when he feels like it) and insular (he communicates mostly in grunts). He’s done superhero films but refuses to live in Los Angeles, preferring the spiritual void of South London, where the only thing thicker than the air pollution is the irony. Hardy is what you get when an entire empire downsizes to one brooding individual and gives him a Screen Actors Guild card.

The international implications keep multiplying. Chinese censors allow his films because the plots are simple—bad men growl, explosions happen, moral ambiguity arrives late and leaves early. European arthouse directors adore him because he can convey twelve stages of grief with a single neck spasm. Even the Iranian film board reportedly screened Bronson as a cautionary tale about unchecked capitalism, which is either a profound misunderstanding or the sharpest critique of neoliberalism since the 2008 crash.

Meanwhile, back in the so-called real world, Hardy volunteers as a Special Constable with the Metropolitan Police, presumably because method acting now requires actual riot gear. It’s comforting to know that when the Thames finally rises to swallow Canary Wharf, at least one off-duty celebrity will be there to hand out traffic tickets to the drowning.

What does it all mean? In an era when nations outsource their wars to mercenaries and their culture to streaming services, Tom Hardy is the last functioning state apparatus left: a self-contained soft-power missile, launched from a dingy pub in Peckham and landing in multiplexes from Mumbai to Minneapolis. He is both product and propaganda, a one-man cultural NATO whose Article 5 clause simply reads: “Try not to bore me.”

And so we watch him stomp across our screens, mumbling sweet nothings to an alien symbiote or driving a flaming guitar truck through the apocalypse, and for two blessed hours the world’s stock markets, submarine cables, and collapsing climate accords fade into background noise. The planet may be on fire, but at least it’s being soundtracked by a man who sounds like he gargles gravel for breakfast. In the end, perhaps that’s all the diplomacy we deserve.