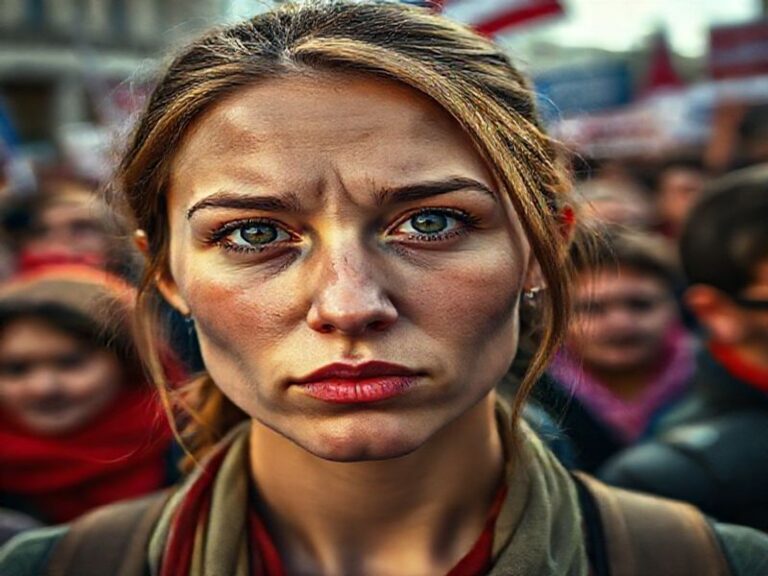

rfk jr

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and the Great American Fever Dream

By Our Correspondent in the Cheap Seats, Somewhere Over the Atlantic

PARIS—Watching Bobby Kennedy III’s namesake crisscross Iowa in a Patagonia vest and a voice hoarse from anti-vax testimonials is, for the rest of the planet, like bingeing a prestige dramedy in which the writers’ room has confused tragedy with farce. To Europeans still politely coughing into masks, RFK Jr.’s campaign is less a political insurgency than a national MRI scan: the contrast dye is conspiracy, the tumors are nostalgia, and the radiologist went to YouTube University.

From the start, the man has been an export commodity. Foreign editors once filed him under “quirky American royalty,” the kind of human interest sidebar that runs next to a photo of a beagle on a surfboard. Then the pandemic hit and RFK Jr.’s Twitter account started sounding like the comments section of a Bulgarian wellness forum. Overnight, his audience ballooned from a few Upper West Side dinner-party contrarians to Brazilian Telegram channels, German eco-moms, and Nigerian pastors who believe 5G turns your kneecaps into Bill Gates’s cryptocurrency. If influence is measured in forwarded voice notes, Kennedy is now a multinational.

The irony, of course, is delicious. A dynasty famous for mandating polio vaccines now produces its own vaccine skeptic, a man who sells vitamin supplements with the same zeal his uncle once sold the Peace Corps. Somewhere in the afterlife, Sargent Shriver is asking for a refund on the family brand license.

Globally, RFK Jr.’s rise tracks the same algorithmic currents that floated Bolsanaro, Modi, and that guy in the Netherlands who thinks Wi-Fi melts tulips. It’s a simple recipe: take declining faith in institutions, add charismatic lineage, sprinkle in actual regulatory failures, and blend until frothy. The finished smoothie can be marketed anywhere trust is low and nostalgia is high—so, basically everywhere. In South Africa, they call him “the American prince who speaks truth to Big Pharma.” In rural France, he’s the only Kennedy who understands the dangers of gluten. In India, WhatsApp uncles forward his clips right between fake Gandhi quotes and discount Viagra ads.

What terrifies foreign ministries isn’t that RFK Jr. might win—bookmakers give him roughly the same odds as the Yellowstone supervolcano erupting on Election Day—but that his talking points metastasize. When a Kennedy says the CIA killed his dad, it carries the imprimatur of aristocracy; the clip is subtitled into 28 languages within the hour. The State Department then spends the next quarter cleaning up bilateral meetings where ministers ask, with the straight face of a man citing Wikipedia, whether the U.S. really did invent AIDS.

Meanwhile, America’s allies practice a diplomatic yoga pose known as “strategic eyebrow arch.” The Germans, who still remember when the Kennedys were the Kennedys, now schedule “vaccine hesitancy containment calls” the way they once scheduled NATO exercises. Canada quietly updated its tourism website to read: “Come for the maple syrup, stay because our herd immunity still functions.” Even the British, who normally treat U.S. politics like a contact sport, have gone uncharacteristically quiet; it’s hard to mock a Kennedy when your own royal family is one Netflix documentary away from becoming a reality show.

And yet, there is something almost admirable in RFK Jr.’s commitment to the bit. While other candidates pivot, he doubles down, a man who has turned contrarianism into cardio. In a world lurching toward managed consensus, here is a candidate willing to say the quiet part into a megaphone: that democracy might just be a group chat with worse graphics. For voters who feel the 21st century has treated them like pop-up ads, that kind of reckless honesty—whether factual or not—feels like oxygen.

The broader significance? Simple. RFK Jr. is not merely running for president; he is beta-testing a post-truth franchise model. If a Kennedy can monetize paranoia, anyone can. The implications ripple outward like a stone dropped in the reflecting pool of every capital where citizens already suspect their leaders are holograms. In that sense, the campaign is less about America 2024 and more about Earth 2030: a planet where legitimacy is crowd-funded and history is whatever trended yesterday.

So buckle up, dear reader. The fever dream is livestreamed, the merch ships internationally, and refunds are definitely not included.